Leonardo Arce Gálvez1,2, Laura Nathaly Ricaurte Gracia2,3, Laura Nataly Rodríguez Torres2

Recibido: 13-07-2025

Aceptado: 23-08-2025

©2026 El(los) Autor(es) – Esta publicación es Órgano oficial de la Sociedad de Anestesiología de Chile

Revista Chilena de Anestesia Vol. 55 Núm. 1 pp. 37-41|https://doi.org/10.25237/revchilanestv55n1-05

PDF|ePub|RIS

Fundamentos para la rotación de opioides. Consideraciones químicas y farmacológicas para la práctica diaria

Abstract

Opioid rotation is a common practice in the care of oncologic and non-oncologic patients. Through the years and the evolution of pharmacological studies, analgesic equipotencies have been defined and different proposals have been made to perform the rotation of an opioid drug when side effects or administration barriers are found, however this is a limited vision since these drugs belong to four chemical groups that give them different characteristics, which should be considered by each health professional in favor of safer practices for patients, especially in complex clinical situations such as cancer and thus obtain better clinical outcomes.

Resumen

La rotación de opioides es una práctica habitual en la atención de pacientes oncológicos y no oncológicos. A través de los años y la evolución de los estudios farmacológicos se han definido equipotencias analgésicas y se han realizado diferentes propuestas para realizar la rotación de un fármaco opioide cuando se encuentran efectos secundarios o barreras de administración, sin embargo, esta es una visión limitada ya que estos fármacos pertenecen a cuatro grupos químicos que les confieren características diferentes, las cuales deben ser consideradas por cada profesional de la salud en pro de prácticas más seguras para los pacientes, sobre todo en situaciones clínicas complejas como el cáncer y así obtener mejores resultados clínicos.

-

Introduction

Opioid drug rotation is a frequent practice in the care of patients with oncologic diseases and chronic pain conditions. It consists of changing one type of medication for another; in general, this practice is carried out due to intolerable side effects, tolerance, poor therapeutic response, changes in the route of administration, drug shortage, or ease of procurement by the patient[1].

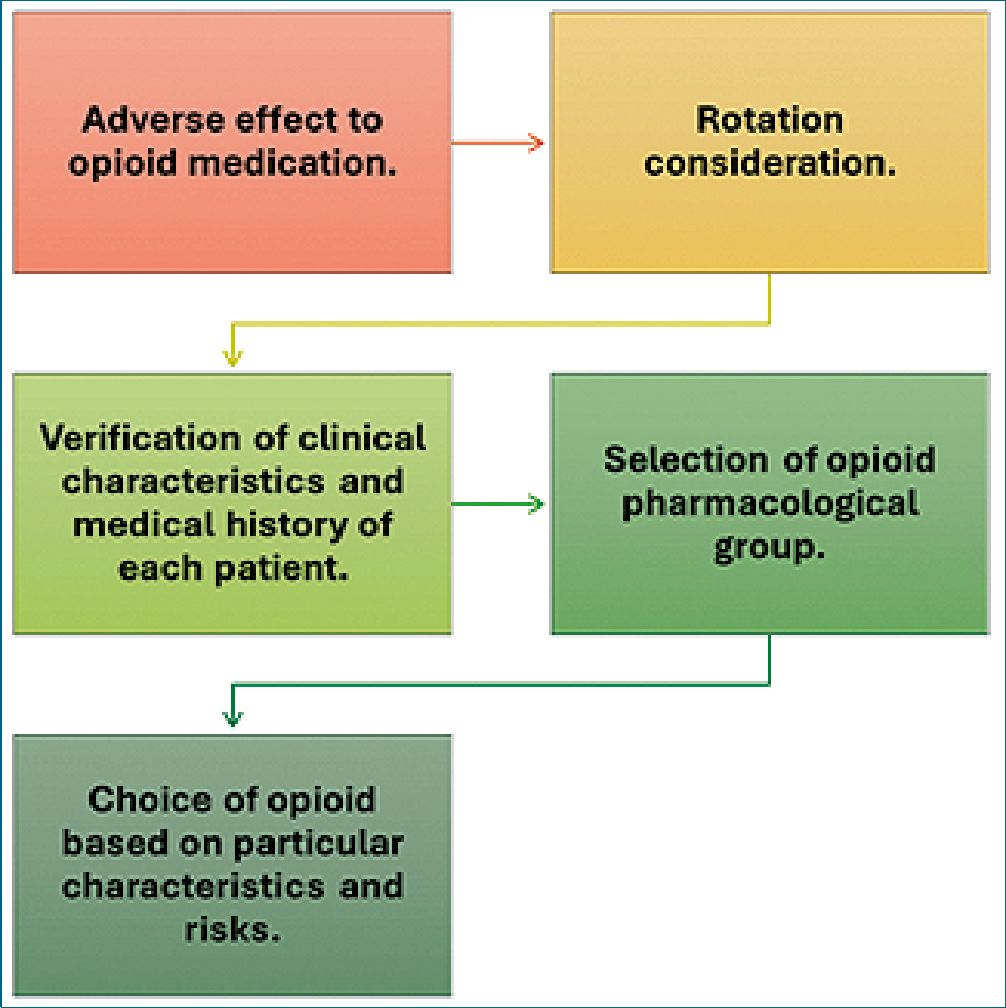

Over the years, different studies and expert consensuses have been carried out where some analgesic equipotencies between one opioid drug and another have been proposed, based on analgesic responses given by patients and clinical experiences, with limited evidence, which makes its application in the general population difficult[2]. The great difficulty of these systems is that they conceptualize opioid drugs as equivalent and a single pharmacological group, however, having a different chemical origin between these types of drugs, which gives them individual pharmacological characteristics, we must begin to consider opioid rotation as a practice that goes beyond calculating the equipotency dose and we must consider which are the pharmacological characteristics that may or may not be indicated in patients improving or aggravating the cause for which the drug was rotated (Figure 1)[3],[4].

-

Chemical and pharmacological characteristics

Drugs classified as opioids are all those that have some effect on the Mu opioid receptor, however, there are other types of receptors such as Kappa, Delta, Zeta, and opioid receptor like (ORL-1). These receptors have modulatory functions in pain, immunological, and endocrinological effects and participate in central mechanisms of dependence, euphoria, and hyperalgesia; they can have antagonistic effects depending on whether the drug can activate or inhibit them[2],[4]. We know that not all opioid drugs activate or inhibit each of these receptors and this is the first point of difference about these drugs (Table 1); it is also known that many of these receptors have heterodimer characteristics that consist in the capacity to activate jointly more than one opioid receptor and have an allosteric regulation in the way they bind with the different drug molecules, which indicates that depending on the place and way of binding a response can be expected that could be very different between one drug and another[5].

Therefore, we found the first important difference between these drugs, and it is the type of opioid receptor where they act and how they bind to this receptor to generate an effect. Considering so many differences in the conception of this pharmacological group, we thought that the most appropriate way to classify these drugs to define their different pharmacological characteristics and perform a rotation would be by chemical structure.

Figure 1. Opioid rotation considerations.

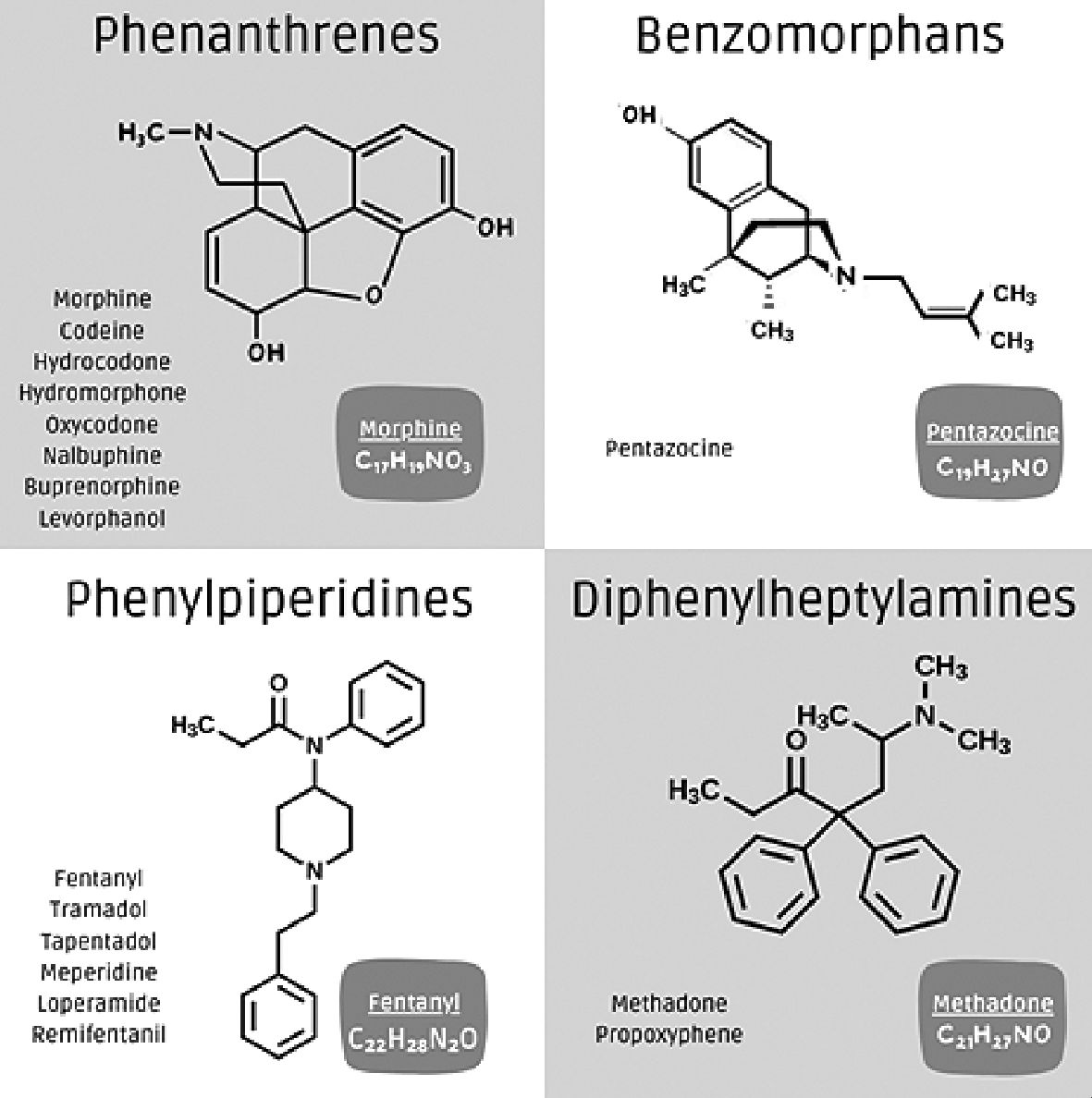

The opioids currently available are classified into: phenanthrenes, benzomorphans, phenylpiperidines, and diphenylheptylamines (Figure 2). Each group has an action on opioid receptors, but there are different pharmacological principles in each.

Table 1. Opioid classified by groups, defining their binding to opioid receptors, as well as histamine release, renal excretion and hepatic metabolites

| Opioid group and type | Mu binding | Kappa binding | Delta binding | Histamine release | Renal excretion % | Hepatic metabolism % |

| Phenanthrenes:- Pentazocine | +++ | ++ | – | ++ | 90% | 60% |

| Benzomorphans: – Morphine | +++ | + | + | +++ | 90% | 10% |

| – Codeine | + | + | + | ++ | 90% | 10% |

| – Hydromorphone | +++ | – | – | 40% | 60% | |

| – Hydrocodone | ++ | – | – | 30% | 60% | |

| – Oxycodone | + | + | – | 20% | 80% | |

| – Buprenorphine | ++ | +* | – | 40% | 60% | |

| Phenylpiperidines:- Fentanyl | +++ | – | – | – | 10% | 90% |

| – Tramadol | + | – | – | – | 60% | 10% |

| – Tapentadol | +++ | – | – | – | 99% | 70% |

| – Meperidine | + | – | – | – | 10% | 90% |

| Diphenylheptylamines:- Methadone | +++ | – | – | +++ | 30% | 90% |

The number of + is related to the intensity of the effect; +*: is an antagonist action.

Figure 2. Opioid drugs classified in their chemical groups.

On the other hand, there are drugs within the same chemical group that present differences, but this is due to the allosteric properties already described in the receptor[4],[5].

Among the phenanthrenes, we find different drugs such as morphine, codeine, hydromorphone, hydrocodone, oxycodone, levorphanol, butorphanol, nalbuphine, and buprenorphine. Within this group, we have some important considerations that will differentiate them at the time of rotation or in daily practice. First, all of them are Mu opioid receptor agonists, except buprenorphine, which is a partial agonist of the Mu opioid receptor and, the antagonist of the ORL1 and Kappa receptors, which gives it an important benefit in fewer side effects, especially neurological and dependence[6]. On the other hand, we should mention that only morphine and codeine have a 6-hydroxyl group which generates more neurological and gastrointestinal side effects, besides having by this route a greater capacity of accumulation and restriction of application in the patient with renal disease, in which case we would prefer the other drugs described, buprenorphine being the safest [6]. From the immunological and endocrinological point of view, morphine and codeine differ in their chemical structure, being the drugs that have the greatest impact on the generation of hypogonadism, hypocortisolism, insulin resistance, infections by large negatives, depletion of innate and acquired immunity, which plays an important role when considering their use[7],[8]. Evaluation of the liver profile of this group, it should be considered that all of them have a CYP (2D6,3A4) mediated metabolism except morphine and codeine, which have a phase II metabolism by glucuronidation; this indicates that in patients with liver damage, all these drugs would have a lower bioavailability except morphine and codeine but could increase their side effects[9].

In the second group, the benzomorphans, we have only pentazocine which is a Mu opioid receptor antagonist agonist with an important side effect related to dysphoria. Due to its receptor antagonist action, it also has an antagonistic role with morphine, reversing above all its cardiovascular effects, generating arterial hypertension; it is considered that it can stimulate the sympathetic pathway in the autonomic nervous system, although its use is currently limited[10].

Phenylpiperidines are an interesting group of opioid drugs, we have drugs such as fentanyl, tramadol, tapentadol, loperamide, and meperidine[3],[11]. All are Mu opioid receptor agonists although they have a lower risk of neurotoxicity compared to phenanthrenes except meperidine; from the renal point of view, it has an adequate profile being the safest fentanyl[12]. From the hepatic outlook, they are metabolized by CYP pathways (2D6, 3A4). Each drug in this group has differing non-opioid mechanisms of action. Tramadol has effects as a serotonin reuptake inhibitor, and noradrenaline reuptake inhibitor, blocks sodium channels, and has a potential effect on TRPV1 nocicep- tors[13]. Tapentadol is a noradrenaline reuptake inhibitor and has a minor clinically insignificant effect on serotonin reuptake, these mechanisms could provide a better profile in neuropathic pain. Fentanyl is a potent drug being the most lipophilic of this group, but with a very short action time which limits its use in some scenarios, despite not having a direct action on serotonin, it shares a common effect of phenylpiperidines and in combination with other serotonergic drugs such as antidepressants, valproic acid or antibiotics such as linezolid can produce a serotonergic syndrome, which should always be considered[14]. Loperamide is an opioid with intraluminal intestinal action that has gastrointestinal effects but does not pass the blood-brain barrier and does not produce analgesic effects. Finally, meperidine has an opioid action of less than 10%, participates in the inhibition of serotonin and noradrenaline reuptake, has antihistaminic, anticholinergic, and alpha 1 and alpha 2 adrenergic agonist action, which reduces its indication as an opioid analgesic, limits its use to different clinical situations and has different potential adverse effects due to its varied mechanisms of action[15].

Finally, diphenylheptylamines include methadone and pro- poxyphene[4]. This pharmacological group acts on the Mu opioid receptor, in the case of propoxyphene also on Kappa receptors due to the heterodimer capacity of the receptors already described. They act additionally on potassium channels, for methadone with a special mention to the hERG channel at the heart site which has the potential to prolong the QT interval and generate arrhythmias[16]. They have a hepatic metabolism by the CYP pathway (3A4, 2B6) and a renal elimination with an intermediate profile in renal failure, methadone having a long half-life and propoxyphene a short one. On the other hand, methadone has an important role in dependence disorders since it generates less tolerance and hormonal impact than morphine and in neuropathic pain, since at the central level, it inhibits glutamatergic NMDA receptors[17],[18].

Knowing the different mechanisms of action and chemical groups of opioid drugs, reduce the rotation of these drugs to the equianalgesic dose is an obtuse view and we must broaden it to all possible considerations to ensure the safety of our patients and pharmacological effectiveness. It is prudent to give two additional considerations to special populations. First, in the pediatric population, there are studies in all opioid groups, but mainly in phenanthrene, especially morphine which can be used even in neonates, in the case of tramadol we have a recommendation for use after 12 years of age to avoid some complications such as ventilatory depression, this associated with the drug profile and the protein conformation of pediatric patients[19],[20]. Secondly, in pregnant patients we indicate to avoid opioids especially to minimize the risk of neonatal abstinence, however, when we have a patient with chronic use or indication for this type of drug, the use of buprenorphine is preferred as a first measure and if another drug is required, rotation to methadone should be considered, the choice of this type of drug is based on maternal-fetal outcomes[21]. A special consideration in the general population and special groups is the histamine release induced by opioid drugs, which is found to a greater or lesser extent in all but the phenylpiperidines, which may generate different hypersensitivity symptoms that tend to be limited but may be enhanced by contact with other drugs[3] (Table 1).

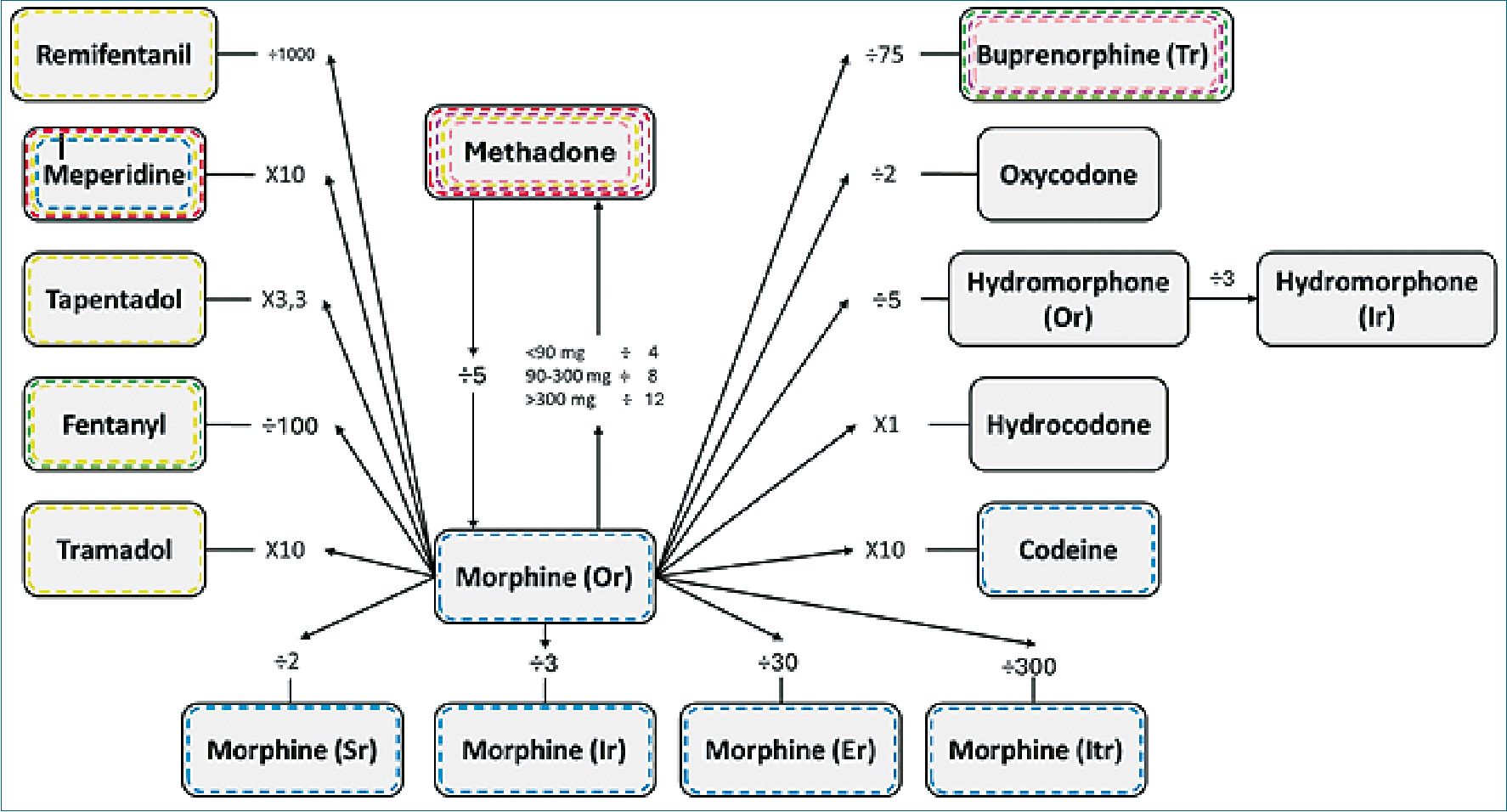

Based on the previous pharmacological analyses and adding the clinical experience and current evidence on opioid rotation, we propose a rotation chart that not only includes equipotency in the values we consider most reasonable, but also general recommendations in common clinical situations such as renal and hepatic pathology, concomitant use with other drugs and special population groups as in all publications describing the rotation of opioids, it is based on the daily oral equivalent dose of morphine, which is equivalent to one unit for each milligram, on the basis of this ratio, it is rotated to another drug (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Opioid rotation model. All rotations start from oral morphine to another drug or route of administration. To perform the opposite operation, it is sufficient to perform the contradiction (multiplication by division and vice versa); **Except for methadone which is dose dependent**. Green: recommended in renal failure; Violet: recommended in dependence; Yellow: serotoninergic risk; Red: cardiovascular risk; Blue: neurotoxicity risk; Pink: alternative in pregnancy. Or: oral route; Sr: subcutaneous route; Ir: intravenous route; Er: epidural route; Itr: intrathecal route; Tr: transdermic route.

-

Conclusion

In conclusion, opioid drug rotation is a process that requires broad pharmacological knowledge to avoid side effects or therapeutic failures. Our objective with this review is to deepen the knowledge of health personnel interested in this practice, as well as to establish safer practices based on recent clinical evidence.

Funding: The authors did not receive funding to carry out this study.

Conflict of interest: We declare no conflict of interest. All available information is included in the article.

-

References

1. Fine PG, Portenoy RK; Ad Hoc Expert Panel on Evidence Review and Guidelines for Opioid Rotation. Establishing “best practices” for opioid rotation: conclusions of an expert panel. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2009 Sep;38(3):418–25. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2009.06.002 PMID:19735902

2. Voon P, Karamouzian M, Kerr T. Chronic pain and opioid misuse: a review of reviews. Subst Abuse Treat Prev Policy. 2017 Aug;12(1):36. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13011-017-0120-7 PMID:28810899

3. Drewes AM, Jensen RD, Nielsen LM, Droney J, Christrup LL, Arendt-Nielsen L, et al. Differences between opioids: pharmacological, experimental, clinical and economical perspectives. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2013 Jan;75(1):60–78. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2125.2012.04317.x PMID:22554450

4. Trescot AM, Datta S, Lee M, Hansen H. Opioid pharmacology. Pain Physician. 2008;11(Suppl):S133-S153. https://doi.org/10.36076/ppj.2008/11/S133

5. Arce Gálvez L, Hernández Abuchaibe D, Cuervo Pulgarín JL, Buitrago Martín CL. Current understanding of opioid receptors and their signaling pathways. Revista Chilena de Anestesia. 2024;53(2):91–3. https://doi.org/10.25237/revchilanestv53n2-04.

6. Fudin JG, Gudin J, Fudin J. A Narrative Pharmacological Review of Buprenorphine: A Unique Opioid for the Treatment of Chronic Pain. Pain Ther n.d.;9. https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.11353028.

7. Plein LM, Rittner HL. Opioids and the immune system – friend or foe. Br J Pharmacol. 2018;175(14):2717-2725. https://doi.org/10.1111/bph.13750

8. de Vries F, Bruin M, Lobatto DJ, Dekkers OM, Schoones JW, van Furth WR, et al. Opioids and their endocrine effects: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2020 Mar;105(3):1020–9. https://doi.org/10.1210/clinem/dgz022 PMID:31511863

9. Ma J, Björnsson ES, Chalasani N. The Safe Use of Analgesics in Patients with Cirrhosis: A Narrative Review. Am J Med. 2024 Feb;137(2):99–106. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjmed.2023.10.022 PMID:37918778

10. Brogden RN, Speight TM, Avery GS. Pentazocine: A Review of its Pharmacological Properties, Therapeutic Efficacy and Dependence Liability. Drugs 1973;5:6-6–7.

11. James A, Williams J. Basic Opioid Pharmacology – An Update. Br J Pain. 2020 May;14(2):115–21. https://doi.org/10.1177/2049463720911986 PMID:32537150

12. Odoma VA, Pitliya A, AlEdani E, Bhangu J, Javed K, Manshahia PK, et al. Opioid Prescription in Patients With Chronic Kidney Disease: A Systematic Review of Comparing Safety and Efficacy of Opioid Use in Chronic Kidney Disease Patients. Cureus. 2023 Sep;15(9):e45485. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.45485 PMID:37727840

13. Subedi M, Bajaj S, Kumar MS, Yc M. An overview of tramadol and its usage in pain management and future perspective. Biomed Pharmacother. 2019 Mar;111:443–51. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopha.2018.12.085 PMID:30594783

14. Rickli A, Liakoni E, Hoener MC, Liechti ME. Opioid-induced inhibition of the human 5-HT and noradrenaline transporters in vitro: link to clinical reports of serotonin syndrome. Br J Pharmacol. 2018 Feb;175(3):532–43. https://doi.org/10.1111/bph.14105 PMID:29210063

15. Buck ML. Is Meperidine the Drug That Just Won’t Die? Volume 16. 2011.

16. Klein MG, Krantz MJ, Fatima N, Watters A, Colon-Sanchez D, Geiger RM, et al. Methadone Blockade of Cardiac Inward Rectifier K+ Current Augments Membrane Instability and Amplifies U Waves on Surface ECGs: A Translational Study. J Am Heart Assoc. 2022 Jun;11(11):e023482. https://doi.org/10.1161/JAHA.121.023482 PMID:35658478

17. Kosten TR, George TP. The neurobiology of opioid dependence: implications for treatment. Sci Pract Perspect. 2002;1(1):13-20. PMCID: PMC2851054. Available from: https://europepmc.org/article/pmc/2851054

18. Fogaça MV, Fukumoto K, Franklin T, Liu RJ, Duman CH, Vitolo OV, et al. N-Methyl-D-aspartate receptor antagonist d-methadone produces rapid, mTORC1-dependent antidepressant effects. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2019 Dec;44(13):2230–8. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41386-019-0501-x PMID:31454827

19. Friedrichsdorf SJ, Goubert L. Pediatric pain treatment and prevention for hospitalized children. Pain Rep. 2019 Dec;5(1):e804. https://doi.org/10.1097/PR9.0000000000000804 PMID:32072099

20. Rodieux F, Vutskits L, Posfay-Barbe KM, Habre W, Piguet V, Desmeules JA, et al. When the safe alternative is not that safe: tramadol prescribing in children. Front Pharmacol. 2018 Mar;9:148. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphar.2018.00148 PMID:29556194

21. Suarez EA, Huybrechts KF, Straub L, Hernández-Díaz S, Jones HE, Connery HS, et al. Buprenorphine versus Methadone for Opioid Use Disorder in Pregnancy. N Engl J Med. 2022 Dec;387(22):2033–44. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa2203318 PMID:36449419

ORCID

ORCID