Mostafa M. Hussein MD.1, Amr Abdelfattah MD.2, Salma Ayman M.Sc.1, Mohamed A. Wareth MD.1

Recibido: 29-08-2024

Aceptado: 03-11-2024

©2025 El(los) Autor(es) – Esta publicación es Órgano oficial de la Sociedad de Anestesiología de Chile

Revista Chilena de Anestesia Vol. 54 Núm. 3 pp. 274-280|https://doi.org/10.25237/revchilanestv54n3-08

PDF|ePub|RIS

Abstract

Introduction: The use of caudal epidural blocks as an adjunct to general anesthesia is common in lumbosacral surgeries. Objective: This study evaluates the efficacy of bupivacaine alone versus bupivacaine combined with dexmedetomidine in caudal epidural blocks as an adjunct to general anesthesia in lumbosacral surgeries. Materials and Methods: Sixty patients undergoing lumbosacral surgery were randomized into Group B (bupivacaine, n = 30), and Group BD (bupivacaine with dexmedetomidine, n = 30). The primary outcome was the time until the first morphine dose for VAS > 3. The secondary outcome was the total opioid consumption in the first 24 hours postoperatively. Results: The groups were comparable in demographic characteristics and hemodynamic parameters at multiple intervals (0.5, 3, 6, 12, 18, 24 hours) with no significant differences (p > 0.05). The addition of dexmedetomidine to bupivacaine significantly extended the duration of postoperative analgesia, as evidenced by a prolonged first time to rescue analgesia and reduced total narcotic consumption in Group BD. The VAS scores at 18 hours, time to first rescue analgesia, and total narcotic consumption showed statistically significant differences favoring the combination therapy (p < 0.05). Conclusion: Fluoroscopically guided caudal administration of bupivacaine with dexmedetomidine improves postoperative pain relief and decreases the need for extra pain medication in lumbosacral surgery patients under general anesthesia compared to bupivacaine alone, with no significant differences in hemodynamic stability between the groups.

Resumen

Introducción: El uso de bloqueos epidurales caudales como coadyuvante de la anestesia general es común en las cirugías lumbosacras. Objetivo: Este estudio evalúa la eficacia de la bupivacaína sola frente a la bupivacaína combinada con dexmedetomidina en los bloqueos epidurales caudales como coadyuvante de la anestesia general en cirugías lumbosacras. Materiales y Métodos: Sesenta pacientes sometidos a cirugía lumbosacra fueron aleatorizados en el Grupo B (bupivacaína, n = 30) y el Grupo BD (bupivacaína con dexmedetomidina, n = 30). El resultado primario fue el tiempo transcurrido hasta la primera dosis de morfina para la EVA > 3. El resultado secundario fue el consumo total de opioides en las primeras 24 h después de la operación. Resultados: Los grupos fueron comparables en características demográficas y parámetros hemodinámicos en múltiples intervalos (0,5, 3, 6, 12, 18, 24 h) sin diferencias significativas (p > 0,05). La adición de dexmedetomidina a la bupivacaína prolongó significativamente la duración de la analgesia posoperatoria, como lo demostró el mayor tiempo en solicitar analgesia de rescate y reducir el consumo total de narcóticos en el grupo BD. Las puntuaciones de la EVA a las 18 h, el tiempo hasta la primera analgesia de rescate y el consumo total de narcóticos mostraron diferencias estadísticamente significativas a favor de la terapia combinada (p < 0,05). Conclusión: La administración caudal fluoroscópica de bupivacaína con dexmedetomidina mejora el alivio del dolor posoperatorio y disminuye la necesidad de analgésicos adicionales en pacientes de cirugía lumbosacra bajo anestesia general en comparación con la bupivacaína sola, sin diferencias significativas en la estabilidad hemodinámica entre los grupos.

-

Introduction

Intravenous opioids are commonly used to control acute pain after spine surgery. By combining different analgesic modalities to achieve better pain relief, spare opioids, and minimize their adverse effects, a caudal epidural block can be used as multimodal analgesia for lumbosacral spine surgery[1].

It is a simple and safe technique that can easily be performed under fluoroscopy in the prone position. The injection site is far from the operative site, which reduces the risk of cerebrospinal fluid leakage and infection[2].

However, the analgesic effect of a single caudal blockade can only last for a short time, even with long-acting local anesthetics. [3] The addition of non-opioid adjuvants such as alpha-2 agonists (e.g., dexmedetomidine) improves both the quality and duration of analgesia[4].

This study aimed to evaluate the effect of perineural administration of dexmedetomidine to bupivacaine in caudal epidural blockade for postoperative analgesia after lumbosacral surgery under general anesthesia, with duration of postoperative analgesia as the primary objective, and postoperative opioid consumption on the first day as the secondary objective.

-

Methods

This prospective, randomized, controlled study was conducted at Ain Shams University Hospitals from August 2023 to June 2024.

Prospective registration was completed at the Pan African Clinical Trials Registry (www.pactr.org) with registration number PACTR202308663873345 and according to the Declaration of Helsinki, written informed consent and approval from the local ethical committee before patient allocation were obtained from the patients (FMASU MS 210/2023).

Adult patients of both sexes, aged 18 to 60 years, an American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) class I and II physical status, undergoing elective lumbosacral surgery with fixation under general anesthesia, were included in the study.

Patients were excluded if they refused written informed consent, had preoperative neurological defects such as sensory or motor dysfunction that impeded informed consent, had an allergy to the drugs used in the study, had contraindications to regional anesthesia (including coagulopathy and local infection), or suffered from substance abuse.

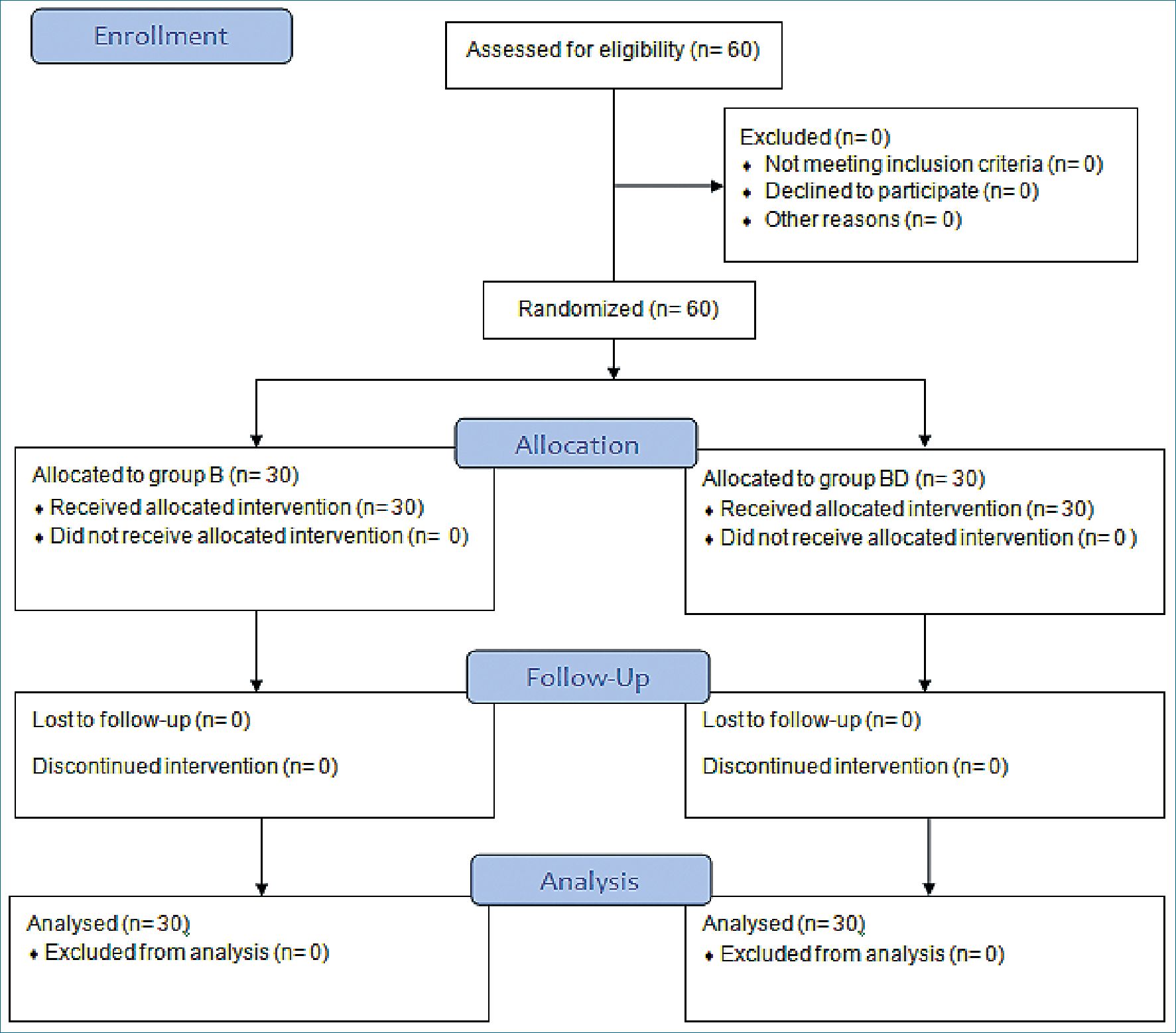

Sixty patients were randomly assigned to one of the following groups using computer-generated codes and opaque sealed envelopes containing the study drugs, with a 1:1 allocation ratio (Figure 1):

Group BD (study group): Patients received 20 ml of plain bupivacaine (0.25%) + 10 pg dexmedetomidine (20 pg/ml) for caudal epidural block. [200 pg amp/10ml = 20*1 (0.5 ml=10 pg)].

Group B (control group): Patients received 20 ml of plain bupivacaine (0.25%) + 0.5 ml of normal saline for caudal epidural block.

All blocks were administered by the same anesthesiologist, a caudal epidural block expert not involved in the study, while different anesthesiologists performed the outcome assessments.

All patients underwent clinical examination (medical history, duration of illness, and medications, especially analgesics), and routine preoperative tests were performed, including complete blood count, coagulation profile, liver function tests, renal function tests, random blood sugar, and electrocardiogram.

The visual analog scale (VAS) was used to assess pain scores before and after the procedure. Scores were recorded by handwriting on a 10-cm line representing a continuum between ‘no pain” at the left end of the scale (0 cm) and the ‘worst pain” at the right end of the scale (10 cm). All patients were informed preoperatively using a scoring system.

Upon arrival in the operating room, standard monitoring including electrocardiography, non-invasive blood pressure, and pulse oximetry was applied. Baseline vital signs and oxygen saturation were recorded.

Intravenous access was established, and intravenous crystalloid fluids were administered. For premedication, prophylactic antibacterial injections (after performing a skin sensitivity test), midazolam 2 mg, granisetron 3 mg, and pantoprazole 40 mg were administered.

In both groups, general anesthesia was induced by intravenous injection of fentanyl 2 pg/kg, propofol (2 mg/kg), and atracurium 0.5 mg/kg.

In both groups, intraoperative preemptive analgesia with intravenous injections of paracetamol (1 gm) and ketorolac (30 mg) was administered as part of multimodal analgesia. After securing the airway, stabilization of the patients, and proper positioning in the prone position, a caudal epidural block was performed.

Intraoperative bradycardia (Heart rate < 60 beats/min) and hypotension (systolic arterial pressure < 90 mmHg) were recorded and managed with atropine 0.01 mg/kg for bradycardia and 20 ml/kg Ringer’s lactate for hypotension.

Specialized equipment was prepared, including an 18G Tuohy epidural needle, a loss-of-resistance epidural syringe, skin antiseptic solution, sterile gloves, and a portable C-arm for fluoroscopy.

Figure 1. The CONSORT flow diagram.

In the prone position, a dry gauze swab was placed in the intergluteal cleft to protect the anal area and genitalia from povidone-iodine, or other disinfectants (especially alcohol) used to disinfect the skin. The anatomical landmarks were then assessed with localization of the underlying sacral hiatus.

After the hiatus was marked, the tip of the index finger was placed on the tip of the coccyx in the intergluteal cleft, while the thumb of the same hand palpated the two sacral cornua located 3-4 cm more rostrally at the upper end of the intergluteal cleft. Sterile skin preparation and draping of the entire region were performed in the usual manner.

Fluoroscopy was performed and a lateral view was obtained to visualize the anatomical boundaries of the sacral canal. Fluoroscopy revealed that the caudal canal appeared as a translucent layer posterior to the sacral segment. The median sacral crest was visualized as an opaque line posterior to the caudal canal. The sacral hiatus can be seen as a translucent opening at the base of the caudal canal.

An 18-gauge Tuohy-type needle was inserted in the midline nto the caudal canal. A slight ”snap” sensation may be appreciated when the advancing needle pierces the sacrococcygeal ligament. Once the needle has reached the ventral wall of the sacral canal, it is slowly advanced cranially to be inserted further into the canal. We used the anteroposterior view once the epidural needle was safely situated within the canal.

The sacral foramina were visualized as translucent and nearly circular areas, lateral to the intermediate sacral crests. A syringe filled with 3 ml of contrast medium was used to document epidural spread and exclude intravascular injection.

Following discharge from the operating room, acute postoperative pain was assessed using the VAS at 30-minute intervals in the Post-Anesthesia Care Unit (PACU) and at 3, 6, 12, 18, and 24 hours postoperatively. Heart rate (HR), mean arterial pressure (MAP), and oxygen saturation were recorded upon arrival in the PACU and every 10 minutes thereafter until discharge. Sedation levels were evaluated at the same intervals on a four-point scale (1 = no sedation, 2 = light sedation, 3 = somnolence, 4 = deep sedation)[5].

If the VAS was > 3 postoperatively, a rescue drug was administered; IV morphine (0.1 mg/kg), to be repeated as needed, maximum every 6 hours. Timing and dose were recorded.

All patients received intravenous ketorolac (30 mg) and paracetamol (1 g) every 8 hours. Any side effects were recorded as hypotension, arrhythmia, bradycardia, nausea or vomiting, or other complications.

The primary outcome was the duration of postoperative analgesia (the time from recovery to the first administered dose of morphine) with a VAS score > 3. The secondary outcome was the total dose of opioids used postoperatively (rescue analgesia) within the first 24 hours.

-

Statistical analysis

-

Sample size calculation

Power Analysis and Sample Size Software (PASS) / version 15.0.10 for sample size calculation, to achieve 99% power, at a significance level of 0.05, after reviewing previous study results showed that the mean duration of analgesia in children who underwent lumbosacral surgeries with general analgesia with bupivacaine with normal saline was lower than those with bupivacaine and dexmedetomidine for a caudal epidural block (4.33 + 0.98 versus 9.88 i 0.90, respectively), a sample size of at least 60 patients undergoing lumbosacral surgeries divided randomly into two groups (30 patients in each group) was sufficient to achieve the study objective. [6] Based on these findings, a sample size of at least 30 patients per group is required.

-

Data analysis

The data were analyzed using the Statistical Package for Social Science (SPSS) version 27.0. Quantitative data were expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD) or median (IQR) where indicated. Qualitative data were expressed as frequencies and percentages.

An independent-sample t-test of significance was used to compare two means. The chi-square test (x2) was used to compare the proportions between the two qualitative parameters. The Mann-Whitney U test was used for two-group comparisons for non-parametric data. The confidence interval was set at 95% and the acceptable margin of error was set at 5%. Therefore, a p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

-

Results

The groups were comparable in demographic data (in terms of age, sex, ASA, and BMI), and there was no statistically significant difference between them (p > 0.05) (Table 1).

Similarly, the groups were comparable in hemodynamic data in terms of MAP and HR at intervals of 0.5, 3, 6, 12, 18, and 24 hours, and there were no statistically significant differences between the groups (p > 0.05) (Table 2).

The groups were also comparable regarding pain data including VAS score at intervals of 0.5, 3, 6, 12, 18, and 24 hours, 1st time of rescue analgesia, and total narcotic consumption. However, there were statistically significant differences between groups in VAS at 18 hours, 1st time of rescue analgesia, and total narcotics consumption (Table 3, 4).

Table 1. Comparison between groups regarding demographic data

| Demographic data | Group B (n = 30) | Group BD (n = 30) | p-value | |

| Age (years) | 53.93 ± 5.5 | 52.07 ± 6.4 | 0.230t | |

| BMI | 30.31 ± 10.5 | 28.68 ± 4.4 | 0.434t | |

| Sex | Male | 16 (53.3%) | 16 (53.3%) | 1 X2 |

| Female | 14 (46.7%) | 14 (46.7%) | ||

| ASA | I | 19 (63.3%) | 16 (53.3%) | 0.436x2 |

| II | 11 (36.7%) | 14 (46.7%) | ||

Data expressed as mean ± SD; number (%); T: = student t-test, x2: = chi square.

Table 2. Comparison between groups regarding hemodynamic data

| Group B (n = 30) | Group BD (n = 30) | p-valuet | |

| MAP 30 min | 83.30 ± 6.2 | 81.80 ± 8.1 | 0.426 |

| MAP 3 h | 83.63 ± 6.3 | 82.43 ± 7.8 | 0.514 |

| MAP 6 h | 85.20 ± 5.9 | 82.93 ± 7.2 | 0.187 |

| MAP 12 h | 86.67 ± 5.8 | 84.00 ± 6.7 | 0.103 |

| MAP 18 h | 88.57 ± 5.7 | 85.60 ± 6.5 | 0.064 |

| MAP 24 h | 89.77 ± 5.0 | 87.17 ± 6.2 | 0.079 |

| HR 30 min | 74.83 ± 6.3 | 71.87 ± 6.9 | 0.089 |

| HR 3 h | 75.23 ± 5.8 | 72.93 ± 6.0 | 0.139 |

| HR 6 h | 76.57 ± 6.4 | 74.17 ± 6.3 | 0.148 |

| HR 12 h | 77.90 ± 6.4 | 75.43 ± 6.2 | 0.133 |

| HR 18 h | 79.63 ± 6.0 | 77.73 ± 6.2 | 0.236 |

| HR 24 h | 81.17 ± 6.2 | 79.73 ± 5.4 | 0.344 |

Data expressed as mean ± SD; t: = student t-test.

No patient in either group developed respiratory depression, urinary retention, nausea or vomiting, or motor or sensory deficits following a caudal epidural block (Table 4).

A significant difference was observed in postoperative sedation. The study group was more sedated than the control group up to 6 hours postoperatively (Table 5).

-

Discussion

This study compared caudal bupivacaine alone versus bu- pivacaine combined with dexmedetomidine for postoperative analgesia in lumbosacral surgery patients under general anesthesia. Bupivacaine combined with dexmedetomidine provided longer analgesia and reduced analgesic requirements compared to bupivacaine alone. Pain scores were comparable during the first 12 hours, likely due to bupivacaine’s lasting effect. After 18 hours, the bupivacaine dexmedetomidine group reported lower pain scores, though differences were not consistently significant thereafter, possibly due to rescue analgesics administered

Table 3. Comparison between groups regarding VAS

| Group B (n = 30) | range | Group BD (n = 30) | Pa | ||||

| range | Median | IQR | Median | IQR | |||

| VAS 30 min | 0 – 2 | 1 | 0 – 2 | 0 – 2 | 1 | 0 – 2 | 0.413 |

| VAS 3 h | 0 – 4 | 1 | 1 – 2 | 0 – 2 | 1 | 1 – 2 | 0.103 |

| VAS 6 h | 1 – 4 | 2 | 1 – 3 | 0 – 4 | 2 | 1 – 2 | 0.111 |

| VAS 12 h | 1 – 4 | 2 | 1 – 2 | 1 – 4 | 2 | 1 – 2 | 0.482 |

| VAS 18 h | 1 – 4 | 2 | 2 – 3 | 1 – 3 | 2 | 1 – 2 | 0.038* |

| VAS 24 h | 1 – 4 | 2 | 2 – 3 | 1 – 4 | 2 | 2 – 2 | 0.661 |

Data are expressed as median, range, and IQR, a: = Mann Whitney test.

Table 4. Comparison between groups regarding postoperative pain and complications

| Group B (n = 30) | Group BD (n = 30) | p-value | |

| 1st dose rescue analgesic (h) | 5.63 ± 1.1 | 6.40 ± 0.9 | 0.004* |

| Total opioid consumption (mg) | 10.17 ± 3.1 | 8.50 ± 3.0 | 0.037* |

| Respiratory depression | 0 | 0 | – |

| Postoperative nausea & vomiting | 4/30 (16.7%) | 1/30 3.3% | 0.663 |

| Motor & sensory deficits | 0 | 0 | – |

| Urinary retention | 0 | 0 | – |

Data are expressed as mean ± SD; number (%); t: = student t-test; x2: = chi-square.

Table 5. Comparison between groups regarding sedation scores

| Group B (n = 30) | Group BD (n = 30) | p-value | |

| 30 min | 1 (1-1) | 3 (2-3) | 0.038* |

| 3 h | 1 (1-1) | 2 (2-3) | 0.039* |

| 6 h | 1 (1-1) | 2 (1-2) | 0.046* |

| 12 h | 1 (1-1) | 1 (1-1) | 0.626 |

| 18 h | 1 (1-1) | 1 (1-1) | 0.745 |

| 24 h | 1 (1-1) | 1 (1-1) | 0.795 |

Data are expressed as median (IQR), and a P value < 0.05 is considered significant.

when pain scores were > 3. Fewer rescue doses overall were needed in bupivacaine dexmedetomidine group.

We chose epidural dexmedetomidine for its fivefold greater pain relief efficacy compared to systemic administration. [7] Performing fluoroscopically guided caudal epidural nerve blocks is preferred over traditional palpation methods. Alternatively, ultrasound-guided identification of the sacral hiatus has also been advocated. The renewed interest in caudal anesthesia stems from the search for safer alternatives to lumbar epidural blocks, especially for patients like those with failed back surgery[8].

Hetta et al., examined 40 pediatric patients undergoing major abdominal cancer surgery. Group I received epidural bupivacaine with dexmedetomidine, and Group II received

epidural bupivacaine alone. They reported that adding dexmedetomidine significantly prolonged arousable sedation during surgery[9].

Konakci et al., demonstrated that combining dexmedetomidine (5 pg) with a local anesthetic in epidural anesthesia provided sedation and stabilized hemodynamics. Despite dexmedetomidine’s dose-dependent impact on blood pressure and heart rate, no significant hypotension or bradycardia requiring treatment was observed[10].

Anand et al., studied adding dexmedetomidine to caudal- ly injected ropivacaine for postoperative pain relief in children undergoing abdominal surgery. They found improved sleep quality, reduced agitation during recovery, and prolonged se- dation[11].

Our findings are supported by Xiang et al., who found that combining caudal bupivacaine with dexmedetomidine (1 pg/ kg) attenuated the hemodynamic response to hernia sac traction in children undergoing inguinal hernia repair[12].

Similarly, according to Yoshitomi et al., dexmedetomidine prolonged analgesic duration during neuraxial blocks with minimal controllable side effects, in contrast to narcotic ad- juncts[13].

Al-Zaben et al., assessed the analgesic effectiveness and side effects of two doses (1 pg/kg and 2 pg/kg) of dexmedetomidine with bupivacaine. They reported higher doses increased side effects like bradycardia, hypotension, and urinary retention, while postoperative pain relief duration remained similar[14].

Dexmedetomidine prolongs bupivacaine’s effect and enhances analgesia by causing local vasoconstriction and increas

ing potassium conductance in nerve fibers. It can also augment local anesthetic action by entering the central nervous system via absorption or cerebrospinal fluid diffusion, where it binds to receptors in the spinal cord and brainstem’s superficial layers or indirectly stimulates spinal cholinergic neurons[15].

Furthermore, in an analysis of the effect of caudal dexmedetomidine, Xiang et al. hypothesized that supplementing caudal bupivacaine with dexmedetomidine prolongs the time of postoperative analgesia[12].

Goyal et al., found that the mean FLACC pain score was significantly less in patients belonging to the bupivacaine-dexme- detomidine group for 12 hours postoperatively than in patients in the bupivacaine group[6].

In line with our findings, Saadawy et al. and Goyal et al., observed that children receiving caudal bupivacaine-dexmedeto- midine required fewer rescue analgesia doses in the first 12-24 hours postoperatively compared to those receiving bupivacaine alone[16],[6].

In our study, patients in the PACU who received bupiva- caine and dexmedetomidine were less agitated and more comfortable compared to those who received bupivacaine alone. Caudal dexmedetomidine extended analgesia duration, reducing postoperative agitation. Similar findings were noted by Goswami et al., who reported significantly prolonged sedation duration in the bupivacaine-dexmedetomidine group compared to the bupivacaine group[17].

Our study found that administering a single bolus dose of caudal dexmedetomidine reduced postoperative restlessness compared to the control group. Dexmedetomidine also extended the duration of caudal block and provided long-lasting pain relief, potentially lowering restlessness after surgery.

In our study, there was no difference between the groups in postoperative urinary retention after catheter removal or nausea and vomiting rates, as all patients received 3 mg of intraoperative granisetron. Previous studies by Gupta et al.[18], reported similar incidences of vomiting and urinary retention between groups receiving bupivacaine with dexmedetomidine or bupivacaine alone. In contrast, Goyal et al.[6], reported higher incidence of nausea and vomiting in the pure bupivacaine group compared to the bupivacaine-dexmedetomidine group.

Limitations of the present study include. The time to postoperative mobilization of the patient was also not studied, as the neurosurgical team had a fixed protocol in this regard and randomization was not possible.

-

Conclusion

Fluoroscopically guided caudal administration of bupiva- caine combined with dexmedetomidine significantly extended postoperative analgesia and decreased the need for additional analgesics compared to bupivacaine alone in patients undergoing lumbosacral surgery under general anesthesia.

Approval from the local ethical committee of the Faculty of Medicine Ain Shams University was obtained (FMASU MS 210/2023).

The authors thank the regional anesthesiologist for their assistance and for performing the regional blocks throughout the study period.

MMH, AMA, SA, MAW: Substantial contributions to conception, study design, data collection, and interpretation. All the authors contributed to the writing and critical review of the manuscript and approved the final version submitted to the journal.

Assistance for the study: None declared.

Financial support and sponsorship: The authors report no involvement in the research by the sponsor that could have influenced the outcome of this work.

Conflicts of interest: No conflict of interest is disclosed by the authors.

-

References

1. Sekar C, Rajasekaran S, Kannan R, Reddy S, Shetty TA, Pithwa YK. Preemptive analgesia for postoperative pain relief in lumbosacral spine surgeries: a randomized controlled trial. Spine J. 2004;4(3):261–4. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.spinee.2003.11.009 PMID:15125846

2. Barham G, Hilton A. Caudal epidurals: the accuracy of blind needle placement and the value of a confirmatory epidurogram. Eur Spine J. 2010 Sep;19(9):1479–83. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00586-010-1469-8 PMID:20512512

3. Beyaz SG, Tokgöz O, Tüfek A. Caudal epidural block in children and infants: retrospective analysis of 2088 cases. Ann Saudi Med. 2011;31(5):494–7. https://doi.org/10.4103/0256-4947.84627 PMID:21911987

4. Vetter TR, Carvallo D, Johnson JL, Mazurek MS, Presson RG Jr. A comparison of single-dose caudal clonidine, morphine, or hydromorphone combined with ropivacaine in pediatric patients undergoing ureteral reimplantation. Anesth Analg. 2007 Jun;104(6):1356–63. https://doi.org/10.1213/01.ane.0000261521.52562.de PMID:17513626

5. Gupta R, Bogra J, Verma R, Kohli M, Kushwaha JK, Kumar S. Dexmedetomidine as an intrathecal adjuvant for postoperative analgesia. Indian J Anaesth. 2011 Jul;55(4):347–51. https://doi.org/10.4103/0019-5049.84841 PMID:22013249

6. Goyal V, Kubre J, Radhakrishnan K. Dexmedetomidine as an adjuvant to bupivacaine in caudal analgesia in children. Anesth Essays Res. 2016;10(2):227–32. https://doi.org/10.4103/0259-1162.174468 PMID:27212752

7. Asano T, Dohi S, Ohta S, Shimonaka H, Iida H. Antinociception by epidural and systemic α(2)-adrenoceptor agonists and their binding affinity in rat spinal cord and brain. Anesth Analg. 2000 Feb;90(2):400–7. PMID:10648329

8. Joo J, Kim J, Lee J. The prevalence of anatomical variations that can cause inadvertent dural puncture when performing caudal block in Koreans: a study using magnetic resonance imaging. Anaesthesia. 2010 Jan;65(1):23–6. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2044.2009.06168.x PMID:19922508

9. Hetta DF, Fares KM, Abedalmohsen AM, Abdel-Wahab AH, Elfadl GM, Ali WN. Epidural dexmedetomidine infusion for perioperative analgesia in patients undergoing abdominal cancer surgery: randomized trial. J Pain Res. 2018 Oct;11:2675–85. https://doi.org/10.2147/JPR.S163975 PMID:30464585

10. Konakci S, Adanir T, Yilmaz G, Rezanko T. The efficacy and neurotoxicity of dexmedetomidine administered via the epidural route. Eur J Anaesthesiol. 2008 May;25(5):403–9. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0265021507003079 PMID:18088445

11. Anand VG, Kannan M, Thavamani A, Bridgit MJ. Effects of dexmedetomidine added to caudal ropivacaine in paediatric lower abdominal surgeries. Indian J Anaesth. 2011 Jul;55(4):340–6. https://doi.org/10.4103/0019-5049.84835 PMID:22013248

12. Xiang Q, Huang DY, Zhao YL, Wang GH, Liu YX, Zhong L, et al. Caudal dexmedetomidine combined with bupivacaine inhibit the response to hernial sac traction in children undergoing inguinal hernia repair. Br J Anaesth. 2013 Mar;110(3):420–4. https://doi.org/10.1093/bja/aes385 PMID:23161357

13. Yoshitomi T, Kohjitani A, Maeda S, Higuchi H, Shimada M, Miyawaki T. Dexmedetomidine enhances the local anesthetic action of lidocaine via an alpha-2A adrenoceptor. Anesth Analg. 2008 Jul;107(1):96–101. https://doi.org/10.1213/ane.0b013e318176be73 PMID:18635472

14. Al-Zaben KR, Qudaisat IY, Abu-Halaweh SA, Al-Ghanem SM, Al-Mustafa MM, Alja’bari AN, et al. Comparison of caudal bupivacaine alone with bupivacaine plus two doses of dexmedetomidine for postoperative analgesia in pediatric patients undergoing infra-umbilical surgery: a randomized controlled double-blinded study. Paediatr Anaesth. 2015 Sep;25(9):883–90. https://doi.org/10.1111/pan.12686 PMID:26033312

15. Gertler R, Brown HC, Mitchell DH, Silvius EN. Dexmedetomidine: a novel sedative-analgesic agent. Proc Bayl Univ Med Cent. 2001 Jan;14(1):13–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/08998280.2001.11927725 PMID:16369581

16. Saadawy I, Boker A, Elshahawy MA, Almazrooa A, Melibary S, Abdellatif AA, et al. Effect of dexmedetomidine on the characteristics of bupivacaine in a caudal block in pediatrics. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2009 Feb;53(2):251–6. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1399-6576.2008.01818.x PMID:19076110

17. Goswami D, Hazra A, Kundu KK. A comparative study between caudal bupivacaine (0.25%) and caudal bupivacaine (0.25%) with dexmedetomidine in children undergoing elective infra-umbilical surgeries. J Anesth Clin Res. 2015;6(11):583–7. https://doi.org/10.4172/2155-6148.1000583 .

18. Gupta D, Ranjan SD, Zestos MM, Jwaida B, Mukhija D, Suson KD, et al. Pre-surgical caudal block, and incidence of postoperative nausea and vomiting after pediatric orchiopexy. Middle East J Anaesthesiol. 2019;26:19–26.

ORCID

ORCID