Víctor Tortorici1,2,*, Andrea Abdul1, Gabriela Bereciartu1, Catherine Feijoo1

Recibido: 10-08-2024

Aceptado: 25-09-2024

©2025 El(los) Autor(es) – Esta publicación es Órgano oficial de la Sociedad de Anestesiología de Chile

Revista Chilena de Anestesia Vol. 54 Núm. 3 pp. 294-301|https://doi.org/10.25237/revchilanestv54n3-11

PDF|ePub|RIS

¿Nos afecta el dolor de otro? Un estudio exploratorio

Abstract

Introduction: Affective conditions are typically overlooked when addressing the mechanisms of pain, although they can transcend the affected individual and result in painful experiences for those who witness suffering. Objective: The main goal of this study was to examine the perception of pain in others (vicarious pain) and the corresponding evoked expression of empathic responses through sensory and affective indicators. Methods: Forty healthy psychology students from UNIMET participated in this study. Using a form called “Am I affected by the pain of others?”, the researchers assessed the empathic effects of three scenarios: imagining a venipuncture procedure, seeing a picture of one, and watching a brief video of it. Pain responses were evaluated using the Visual Analogue Scale. Results: Affective indicators reflected the pain response evoked by different scenarios more appropriately than sensory indicators. How painful scenarios were presented influenced the participants’ empathic responses (video > picture/imagination). Interestingly, cluster analysis revealed a dynamic castling of participants through different conglomerates when changing scenarios. Discussion: Understanding the impact of empathy on pain is crucial for caregivers to help their patients effectively and avoid painful consequences. Therefore, it is essential to consider the affective aspects of pain during anamnesis. Relying solely on sensory descriptors may not be sufficient to explain what triggers pain. Conclusion: Considering the emotional/affective dimension is a key element of the pain equation. Painful situations may lead to pro-nociceptive effects in observers, altering their empathic responses and causing them to feel and misjudge the pain of others.

Resumen

Introducción: Las condiciones afectivas suelen pasarse por alto cuando se consideran los mecanismos involucrados con el dolor, aunque pueden trascender a la persona que las sufre y dar lugar a experiencias dolorosas en quienes presencian su sufrimiento. Objetivo: El objetivo principal de este estudio fue examinar la percepción del dolor de otros (dolor vicario) y la correspondiente expresión de respuestas empáticas a través de indicadores sensoriales y afectivos. Métodos: En este estudio participaron cuarenta estudiantes de psicología, sin condiciones dolorosas en curso, de la UNIMET. Utilizando un formulario denominado “¿Me afecta el dolor ajeno?”, los investigadores evaluaron los efectos empáticos de tres escenarios: imaginar un procedimiento de venopunción, ver una imagen de ese procedimiento y ver un breve vídeo que lo ilustre. Las respuestas de dolor se evaluaron mediante la Escala Visual Analógica. Resultados: Los indicadores afectivos reflejaron de forma más adecuada la respuesta de dolor evocada por los distintos escenarios en comparación con los indicadores sensoriales. La forma en que se presentaron los escenarios dolorosos influyó en las respuestas empáticas de los participantes (vídeo > imagen/imaginación). De manera interesante, el análisis de conglomerados reveló una rotación dinámica de los participantes a través de diferentes conglomerados al cambiar de escenario. Discusión: Comprender el impacto de la empatía en el dolor es crucial para que los cuidadores puedan ayudar a sus pacientes de forma eficaz y evitar consecuencias dolorosas. Lo anterior sugiere que es esencial tener en cuenta los aspectos afectivos del dolor durante la anamnesis. Basarse únicamente en los descriptores sensoriales puede no ser suficiente para explicar aquello que desencadena el dolor. Conclusiones: Considerar la dimensión emocional/afectiva es un elemento clave de la ecuación del dolor. Las situaciones dolorosas pueden provocar efectos pronociceptivos en los observadores, alterando sus respuestas empáticas y haciendo que sientan y juzguen erróneamente el dolor de los demás.

-

Introduction

In terms of healthcare, the relationship between a person experiencing pain and a caregiver (e.g., medical and paramedical staff, family members, or a well-intentioned neighbor) can affect the perception of pain in both senses, even exposing caregivers to the risk of stress, overload, exhaustion, or persistent pain without a physical cause[1]. Despite this, the role of affective modulation of others’ pain remains unclear. According to the International Association for the Study of Pain (IASP)[2], pain is a sensorial and emotional experience associated with, or similar to, actual or potential tissue damage. Humans can establish relationships that help us connect more deeply as social beings. Empathy is the ability to understand and share the feelings of others. Various stimuli can influence this, including pain, which affects the perception and understanding of the nociceptive state experienced by others[3]. Through empathy, someone other than the sufferer can perceive or infer a painful sensation by imagining or observing it, a phenomenon known as vicarious perception of pain[4]. Vicarious experiences may influence the empathy and objectivity needed to care appropriately for someone experiencing pain. The main objective of this study was to evaluate the vicarious perception of pain expressed through sensory and affective indicators in psychology students at UNIMET.

-

Methodology

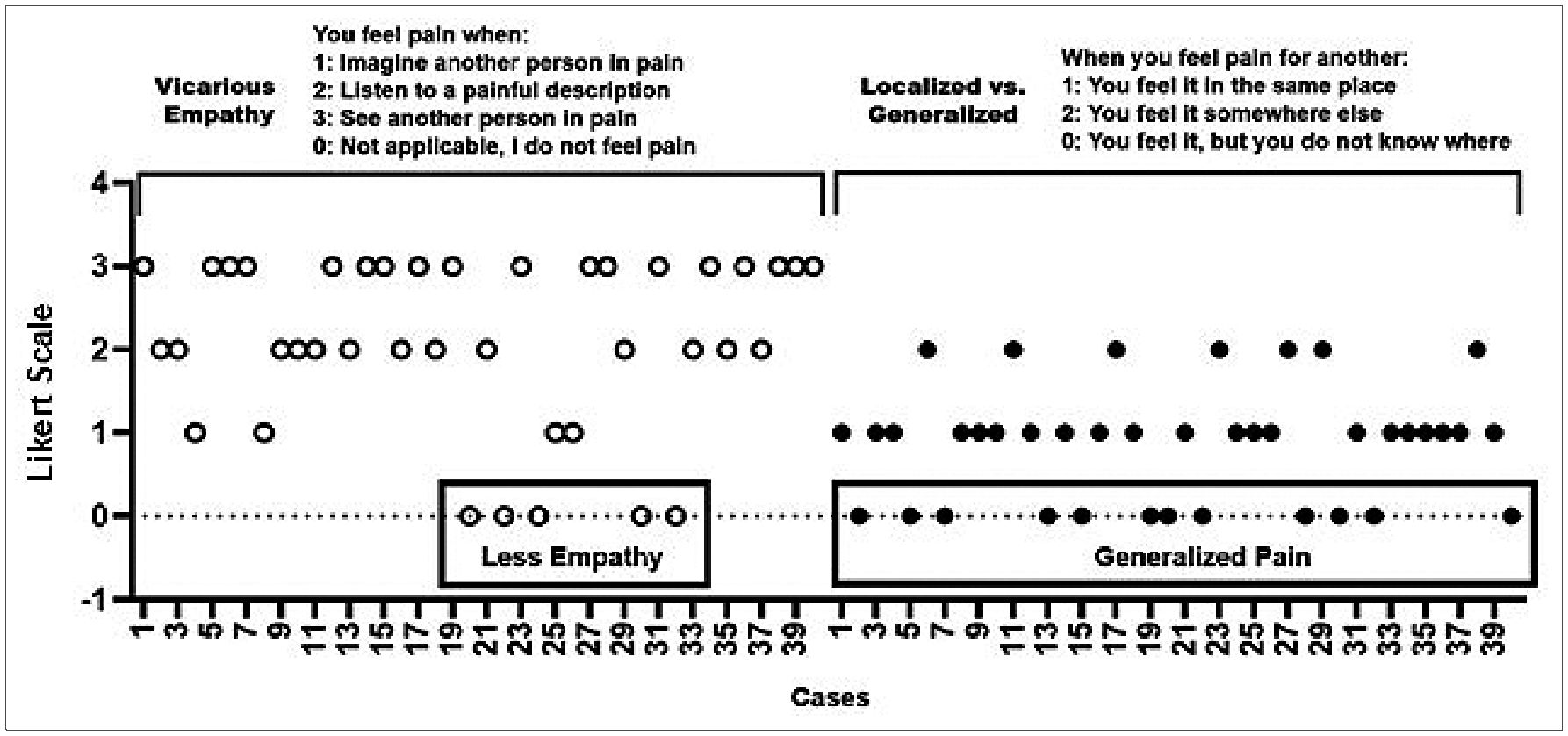

This study was performed at the Neuroscience Laboratory of UNIMET. The sample included 40 healthy psychology students of both sexes aged 18-25 years. Inspired by the Empathy for Pain Scale[5], data collection involved the design of a form called “Am I Affected by the Pain of Others?”. It contained 104 items divided into four sections and allowed the assessment of the empathic effect of an invasive clinical procedure (venipuncture: peripheral venous puncture) that can cause pain. The first three sections of the form assessed the impact of the three scenarios. The first involved the evocation of a venipuncture procedure and the use of imagination. The second scenario used a photograph alluding to the procedure (freeze image taken from the video https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=aq8OwFaIQ4I). In contrast, the third scenario showed a short (edited and muted) version of the video mentioned above (Core Emergency Medicine, Core EM). Participants evaluated each of the three scenarios for 30 seconds. Fourteen sensory (discomfort, nausea, tingling, pain, stiffness, throbbing sensation, burning, shooting sensation, itching, sweating, hypotension, dizziness, cold, and electric shock sensation) and affective indicators (sadness, disgust, fear, desire to cry, desire for accompaniment, compassion, willingness to be alone, cruelty, desire to look away, anguish, desire to get away, desperation, disgust, and empathy toward others) were used to evaluate these scenarios based on Likert-type scales ranging from 1 to 5, where 1 represented the absence and 5 the maximum value assigned to the indicator. The fourth section of the form evaluated the nociceptive impact of the scenarios on the participants by using additional inquiries related to their experience with the pain of others and the possible localization of the noxious stimulus in their own body (somatization). This final section was evaluated from the point of view of vicarious empathy and the location of pain evoked by the scenarios. For vicarious empathy, the Likert scale ranged from 0 to 3 to rate whether participants felt pain when they imagined another person in pain (1), heard a painful description (2), saw another person in pain (3), or did not apply because they did not feel pain (0). Somatization was evaluated with a Likert scale of only three digits to indicate whether the participants felt the other’s pain in the same place on their body (1), in another place (2), or if, even though they felt it, they could not locate where they felt it (0). Thus, it was possible to determine whether the pain evoked was localized or generalized.

Before being distributed to the participants, the form was submitted for expert validation involving five local anesthesiologists and clinical pain specialists, all members and former presidents of The Venezuelan Association for the Study of Pain (AVED, the Venezuelan chapter of the IASP), using Lawshe’s model[6], modified by Tristan-Lopez[7], which classified the form items into three categories (essential, helpful, and not necessary). Experts selected one category for each item on a form and noted their observations. Their analysis yielded a Content Validity Index of 0.903, higher than the minimum required value (0.70). Therefore, the instrument was considered valid for meaningful assessment and quantification of the relationship between pain and empathy.

The form also included the operational definition of the pain perceived by participants after sequentially considering the three scenarios of venipuncture using a Visual Analog Pain Scale (VAS), which is a Likert scale ranging from 0 to 10, where 0 represents the absence of pain and 10 the maximum pain the participant can indicate.

We excluded people who experienced physical pain or affective disturbances to optimize the study conditions when the form was administered. These criteria allowed participants to be rejected if they were taking analgesics, had recurrent fainting spells, had blood pressure problems, had any active injury that caused pain, or were in their menstrual phase or a state of pregnancy.

After obtaining the results, descriptive statistical analysis was performed to determine the mean and standard error as measures of central tendency. The Kolmogorov-Smirnov test was then applied to evaluate whether the data were Gaussian in distribution. Parametric statistics were applied based on this assumption. The student’s t-test was used to validate the significance between two groups or conditions, and oneway ANOVA, followed by its corresponding post-hoc analysis (Bonferroni’s multiple comparisons test), was used to compare three or more groups. The coefficient of determination (square of Pearson’s correlation coefficient) assessed the strength of the relationship between variables. The statistical significance threshold was set at p < 0.05, followed by a 95% CI to verify its precision. To deepen the review of the results, cluster analysis (K-means clustering using Ward’s method) was performed to divide the sample into defined groups based on the responses generated by the different scenarios according to the difference in the contribution of sensorial and affective indicators vs. the VAS values. This analysis divided a set of 40 observations into 6-7 groups per scenario, where each observation belonged to the group closest to its mean value.

This study was approved by the Research Advisory Commission, a division of the Research and Development Directorate of UNIMET, before starting the experimental procedures following the recommendations of the Declaration of Helsinki of the World Medical Association (WMA)[8]. This study also followed the ethical guidelines for human pain research of the IASP[9]. Subjects were informed of the tasks they were about to perform, and their signed consent was requested for investigation before starting the study. The participants signed a confidentiality agreement that allowed the use of the study data for academic and research purposes, including the publication of the findings. Lastly, participants’ identities were kept anonymous during each study phase.

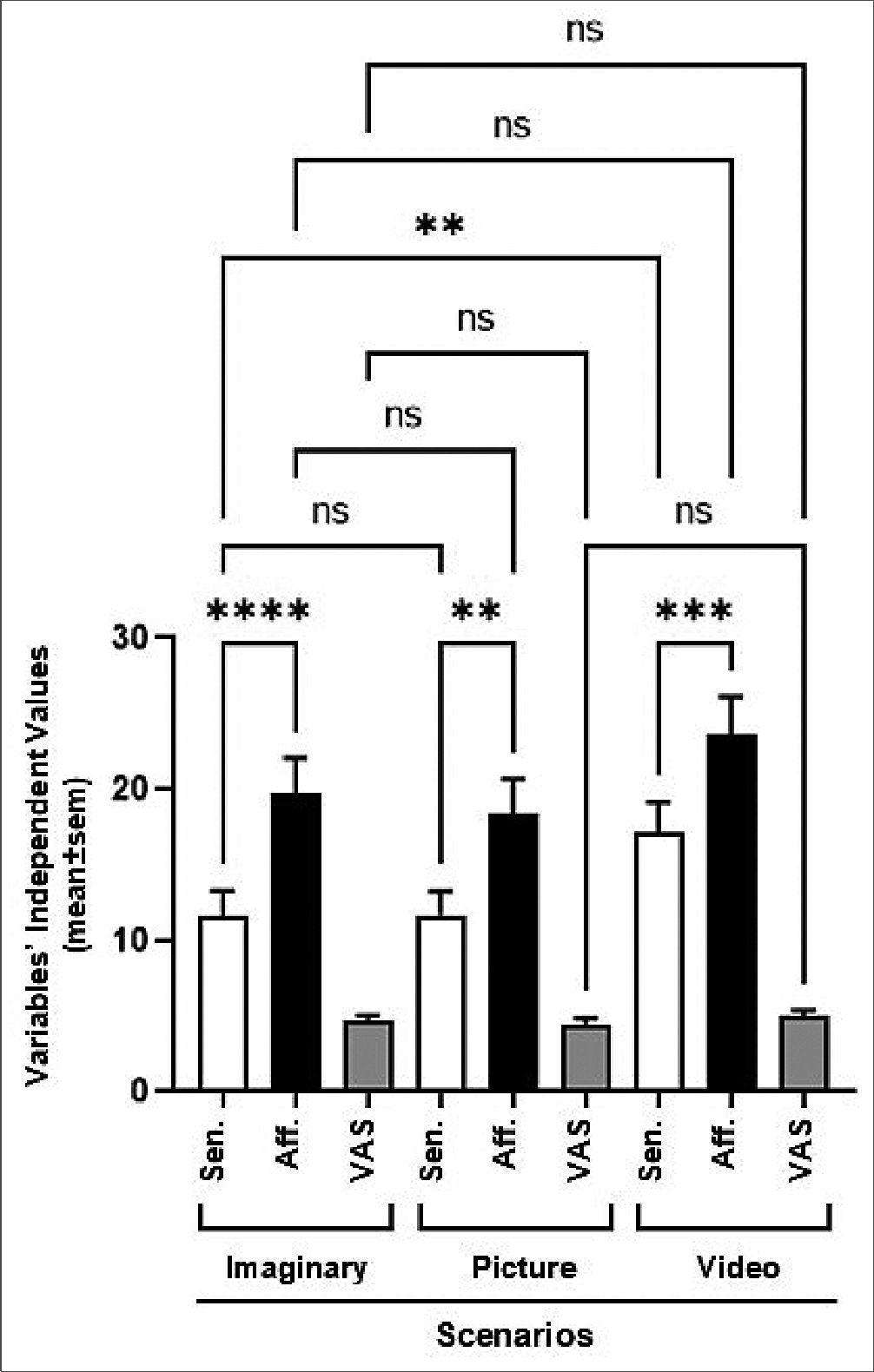

Figure 1.

-

Results

One of the most striking findings of this study was the use of affective indicators (often not assessed during anamnesis) to describe the effects evoked by the scenarios. As seen in Figure 1, the video scenario evoked the highest response for both types of indicators (p < 0.01) but to a significantly greater extent for affective indicators (p < 0.001), suggesting that vicarious consideration of different nociceptive contexts modified the empathic response of participants. Additionally, the presentation modality of the nociceptive situations affected the generation of the empathic response among participants (vid- eo>picture/imaginary). Despite the apparent need to consider affective indicators in the explanation of vicarious pain and that the sole use of sensory indicators was not sufficient, Figure 1 also shows that the non-segmented processing of the data was not adequate to establish differences in terms of the intensity of the pain perceived by observers when exposed to the three conditions. To solve this problem, a cluster analysis was performed for each scenario.

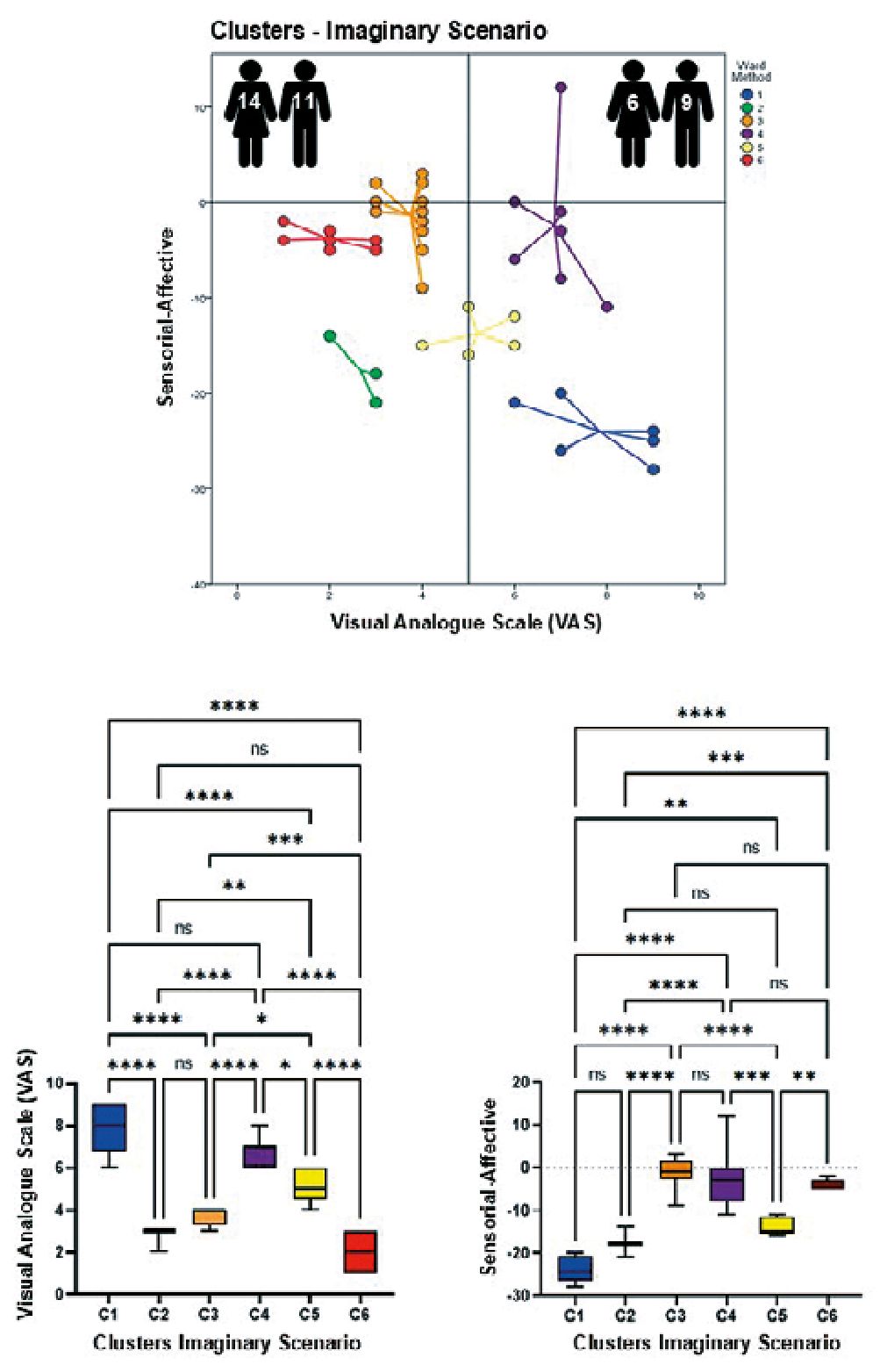

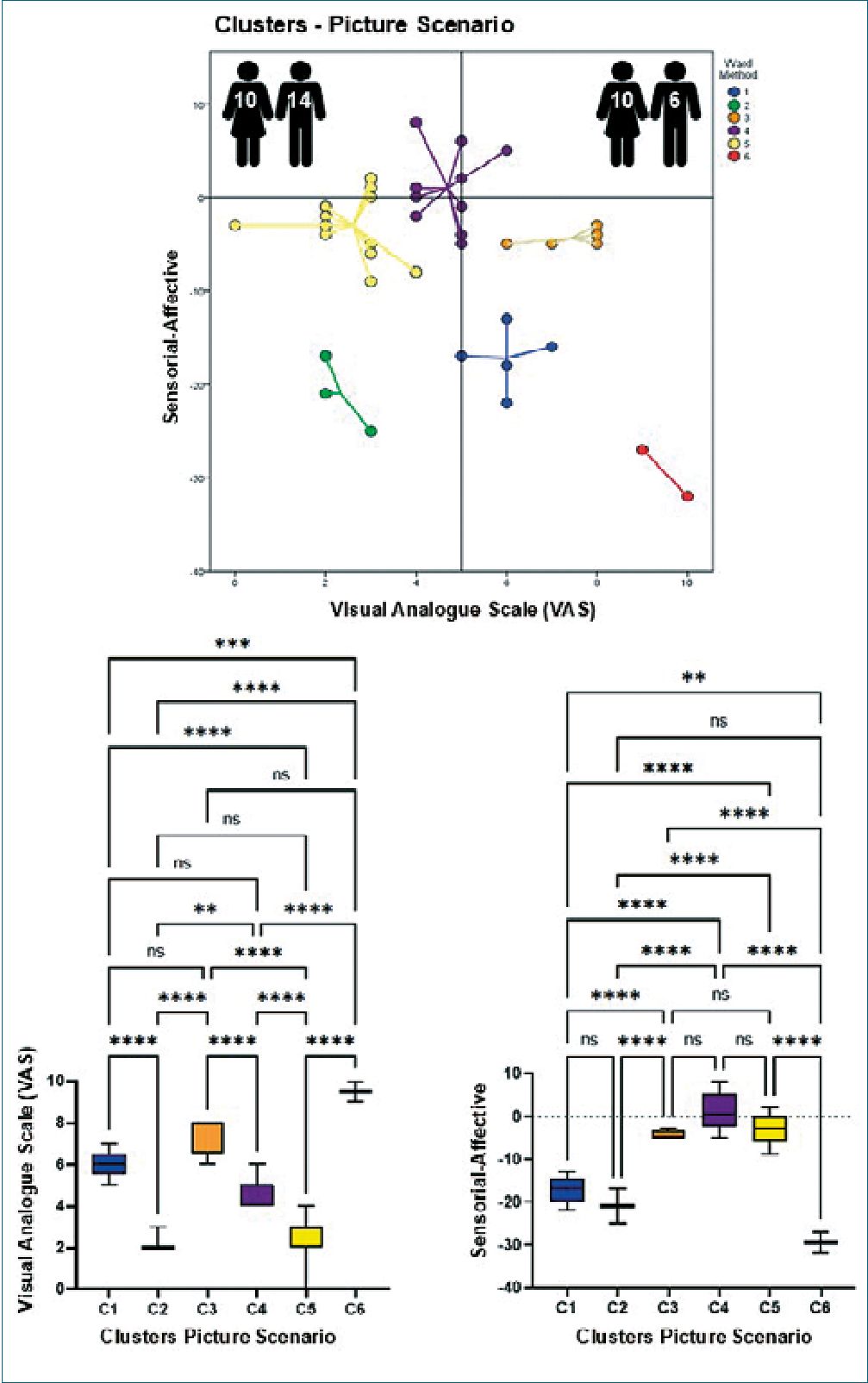

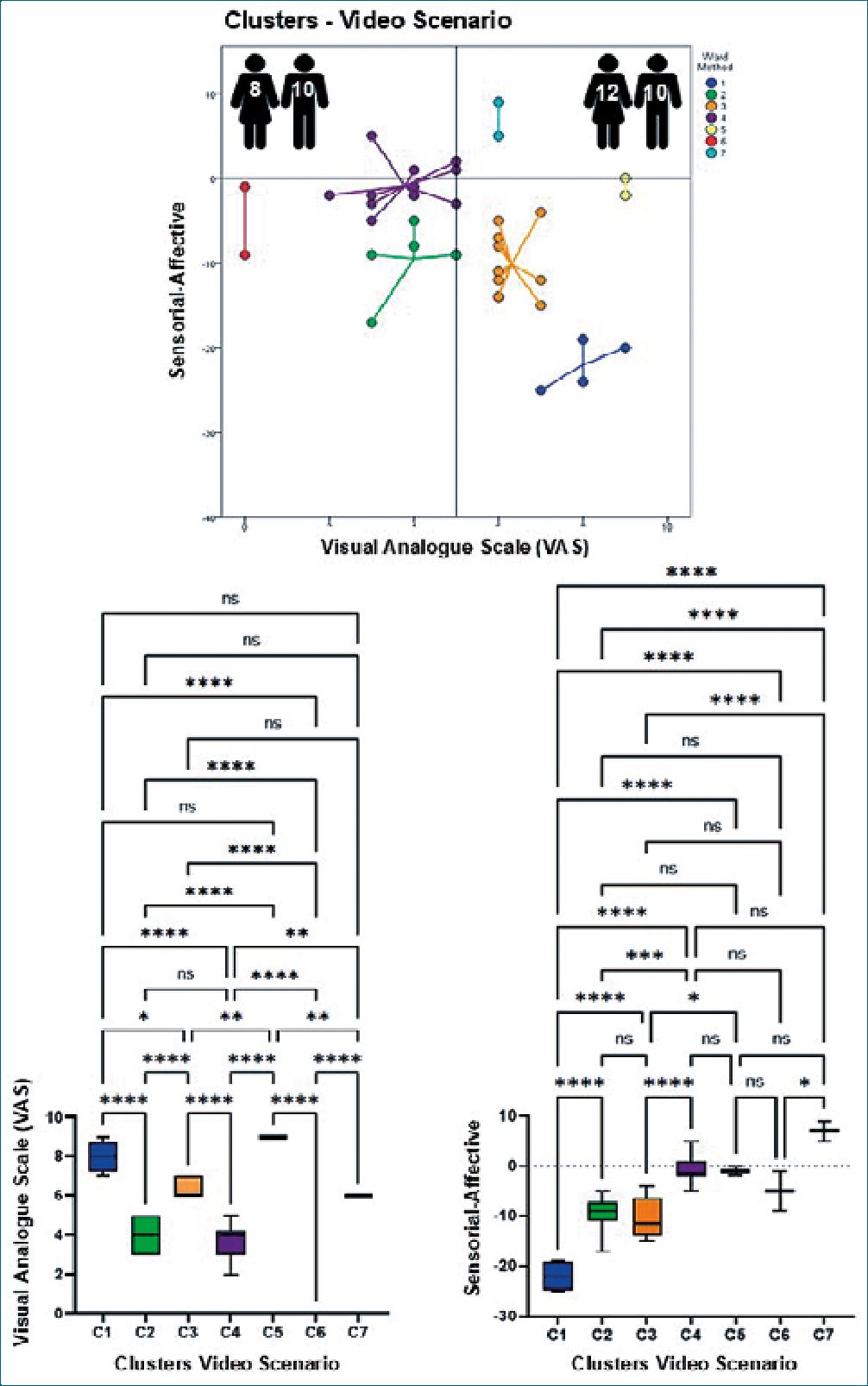

Figures 2-4 show in their upper parts scatterplots of the differences between the sensorial and affective indicators reported by the participants vs. their corresponding VAS values. Negative values of the difference between indicators reflected higher affective qualifications. The vertical line that touched 5 on the VAS axis divided participants into two groups, experiencing less or more pain when exposed to different scenarios. The number of male and female participants is at the top of each graph. It is essential to mention that the original identity of each cluster remained unaltered if at least two original participants did not permute to another cluster. The lower part of the figures shows the results of the ANOVAs for the VAS values and the difference between the indicators per scenario, which helped to support the clustering process. Tables 1-3 show the statistical analysis results and a summary of the dynamic changes, including the tendency to express higher pain values, particularly in female participants, when moving successively through the scenarios.

As shown, individuals gathered around 6-7 different clusters, suggesting heterogeneous viewpoints. Interestingly, the sequential presentation of various scenarios (imaginary, picture, and video) generated a dynamic migration of participants between clusters. This transition, which represents changes in perception quality, was more evident in clusters 3, 5, and 6, which moved from lower to higher pain values. Interestingly, the opposite trend was observed for cluster 6. Two other clusters were more resilient to changes, remaining throughout the experience with higher (cluster 1) or lower (cluster 2) pain values. Regarding the difference between sensorial and affective indicators in qualifying the scenarios, most participants felt that affective indicators described their opinions more appropriately. However, the video scenario promoted the appearance of a new cluster (cluster 7) with two members that opposed the behavior of the majority and preferred the use of sensorial indicators for their interpretation of the scenario while expressing a high level of pain. On the other hand, only in the imaginary scenario males (Table 3 and 4) felt more pain, probably because most of the male participants imagined themselves as protagonists of the venipuncture process, which was not liked by the majority.

In addition, as shown in Figure 5, 87.50% of the participants reported that they could experience vicarious pain when they imagined or saw another person in pain or heard someone describe an injury or pain (see>listen>imagine). Furthermore, 52.50% of participants reported experiencing pain in the same part of their body as the other person, demonstrating a clear somatization of another person’s pain without an apparent physical cause. Other participants also claimed to feel pain somewhere else in their bodies (17.50%), while the rest (30.00%) found it challenging to define its location.

As can be seen, the results reflect that vicarious viewing of different nociceptive contexts may generate pro-nociceptive (painful) effects in the observer, modifying their empathic response and even somatizing the pain of the other. Stimulus presentation was significantly important, with the short video scenario producing the highest level of affectation. The results also highlight the significant empathic effect promoted by affective indicators over sensory indicators, suggesting that both were determinants when evaluating the presented contexts.

Figure 2.

Figure 3.

-

Discussion

Pain is associated not only with clinical aspects but also with social and cultural factors. Contextual facts can influence painful experiences, adding affective and cognitive aspects to individual perception and affecting both intensity and tolerance to pain[10]. It also highlights the concept of empathy, defined as a phenomenon of affective resonance, cognitive perception, and emotional regulation that facilitates prosocial interaction[11], aligning the coincidence of the states observed in other people with representations of our own body5. Thus, when we see another person experiencing pain, we may feel a localized and referred sensation in our body in the same affected region as the other person[4].

| Table 1. One-way ANOVA multiple comparisons – VAS analysis | ||||||||

| Imaginary Scenery | Cluster 1 | Cluster 2 | Cluster 3 | Cluster 4 | Cluster 5 | Cluster 6 | Anova | |

| Number of values | 6 | 3 | 12 | 7 | 5 | 7 | F (5.34 = 53.05 | |

| Mean | 7.533 | 2.667 | 3.750 | 6.857 | 5.200 | 2.000 | p < 0.0001 | |

| Std. Error of Men | 0.5428 | 0.3333 | 0.1308 | 0.2608 | 0.3742 | 0.3086 | R* = 0.8864 | |

| Lower 95%CI | 6.438 | 1.232 | 3.463 | 6.219 | 4.161 | 1.245 | ||

| Upper 95% Cl | 9.228 | 4.101 | 4.037 | 7.495 | 6.239 | 2.755 | ||

| Picture Scenery | Cluster 1 | Cluster 2 | Cluster 3 | Cluster 4 | Cluster 5 | Cluster 6 | Anova | |

| Number of values | 5 | 3 | 5 | 9 | 15 | 2 | F (5.33) = 47.09 | |

| Mean | 6.000 | 2.333 | 7.400 | 4.667 | 2.600 | 9.500 | p < 0.0001 | |

| Std. Error of Mean | 0.3182 | 0.3333 | 0.4000 | 0.2357 | 0.2545 | 0.5000 | R* = 0.8775 | |

| Lower 95% CI | 5.122 | 0.8991 | 6.289 | 4.123 | 2.054 | 3.147 | ||

| Upper 95% Cl | 6.878 | 3.768 | 8.511 | 5.210 | 3.146 | 15.85 | ||

| Video Scenery | Cluster 1 | Cluster 2 | Cluster 3 | Cluster 4 | Cluster 5 | Cluster 6 | Cluster 7 | Anova |

| Number of values | 4 | 6 | 10 | 14 | 2 | 2 | 2 | F (6.34) = 48.70 |

| Mean | 8.000 | 4.000 | 6.300 | 3.786 | 9.000 | 0.000 | 6.000 | p < 0.0001 |

| Std. Error of Mean | 0.4082 | 0.3651 | 0.1528 | 0.2386 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | R* = 0.8995 |

| Lower 95% CI | 6.701 | 3.061 | 5.954 | 3.270 | 9.000 | 0.000 | 6.000 | |

| Upper 95% Cl | 9.299 | 4.939 | 6.646 | 4.301 | 9.000 | 0.000 | 6.000 | |

| Table 2. One-way ANOVA multiple comparisons – Sensorial vs. affective indicators analysis | ||||||||

| Imaginary Scenery | Cluster 1 | Cluster 2 | Cluster 3 | Cluster 4 | Cluster 5 | Cluster 6 | Anova | |

| Number of values | 6 | 3 | 12 | 7 | 5 | 7 | F (5.34) = 35.25 | |

| Mean | -24.00 | -17.67 | -1.333 | -2.429 | -13.80 | -3.857 | p < 0.0001 | |

| Std. Error of Mean | 1.238 | 2.028 | 0.9561 | 28.19 | 0.9695 | 0.4041 | – | |

| Lower 95% CI | -27.18 | -26.39 | -3.438 | -9.326 | -16.49 | -4.846 | R* = 0.8383 | |

| Upper 95% Cl | -20.82 | -8.943 | 0.7710 | 4.489 | -11.11 | -2.868 | ||

| Picture Scenery | Cluster 1 | Cluster 2 | Cluster 3 | Cluster 4 | Cluster 5 | Cluster 6 | Anova | |

| Number of values | 5 | 3 | 5 | 10 | 15 | 2 | F (5.34) = 46.47 | |

| Mean | -17.20 | -21.00 | -4.400 | 1.000 | -3.000 | -29.50 | p < 0.0001 | |

| Std. Error of Mean | 1.463 | 2.309 | 0.4000 | 1.358 | 0.9361 | 2.500 | – | |

| Lower 95% CI | -21.26 | -30.94 | -5.511 | -2.072 | -5.008 | -61.27 | R* = 0.8730 | |

| Upper 95% Cl | -13.14 | -11.06 | -3.289 | 4.072 | -0.9924 | 2.266 | ||

| Video Scenery | Cluster 1 | Cluster 2 | Cluster 3 | Cluster 4 | Cluster 5 | Cluster 6 | Cluster 7 | Anova |

| Number of values | 4 | 6 | 10 | 14 | 2 | 2 | 2 | F (6.33) = 30.13 |

| Mean | -22.00 | -9.500 | -10.20 | 0.9286 | -1.000 | -5.000 | 7.000 | p < 0.0001 |

| Std. Error of Mean | 1.472 | 1.628 | 1.245 | 0.6668 | 1.000 | 4.000 | 2.000 | – |

| Lower 95% CI | -226.68 | -13.68 | -13,02 | -2.369 | -13.71 | -55.82 | -18.41 | R* = 0.8546 |

| Upper 95% Cl | -17.32 | -5.315 | -7.383 | 0.5120 | 11.71 | 45.82 | 3241 | |

Figure 4.

There is evidence that observing someone in pain causes pain to the observer[12]. Interestingly, the brain regions responsible for the affective processing of pain and those responsible for analyzing the sensory and discriminative properties of a noxious stimulus are simultaneously activated when someone is suffering[13]. Thus, observing the pain of others leads to vicarious experiences[14].

Neuroscience helps us to understand aspects such as compassion. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain has identified neural networks that are activated in people who feel the pain of others. These networks are activated when we experience first-hand (oneself) pain but also when experiencing vicarious pain[15]. These overlapping neural structures are located in lateral and medial brain regions[16], and their simultaneous activity can facilitate empathic understanding[17]. However, other authors have suggested the existence of distinct specialized circuits required to experience others’ suffer- ing[18], including networks synchronized during the observation of physical pain, different (according to them) from those engaged in affective pain empathy[19]. Hence, these networks’ dynamic and complex nature supports the notion that empathy for pain is a multifaceted social cognitive process that deserves consideration.

Based on the above findings and considering the lack of information on this topic in our country, the following question arose: How does a nociceptive stimulus applied to a third person impact the empathic response of psychology students at the UNIMET? In addition to its importance in clinical practice, this phenomenon is particularly relevant for professionals working in helping fields, such as psychologists, therapists, and social workers, who are often faced with the traumatic histories of their patients. Empathy plays a crucial role in this process, as it allows professionals to connect with the pain of others, but it can also lead to significant emotional exhaustion.

Figure 5.

Table 3. Summary of changes per scenario

| Less Paln | More Paln

37.50% Males |

||

| Vicarious Pain | 62.50%

Females |

||

| Imaglnary Scenario | Sex | ||

| Preference for affective indicators | 85.00% | 92.86% | |

| Vicarious pain | 60.00% | 40.00% | |

| Sex | Males | Females | |

| Picture Scenario | Preference for affective indicators | 76.47% | 91.67% |

| Vicarious pain | 45.00% | 55.00% | |

| Sex | Males | Females | |

| Video Scenario | Preference for affective indicators | 87.50% | 88.24% |

The idea was to evaluate human pain by imagining or observing others’ pain and to consider how empathy was affected by this interpretation. These results will contribute to expanding the body of knowledge to understand the mechanisms responsible for pain interpretation and how they can be modified through affection, which is one of the fundamental goals of the recently created Neuroscience Laboratory at UNIMET. Contributing to people’s physical and mental well-being and consequently achieving a better quality of life is one of the main goals of any pain-associated specialist. Therefore, understanding the impact of empathy on painful conditions should be considered an essential task. Perhaps consciously feeling another person’s physical pain mainly results from emotional contagion and reactivity, promoting socially elicited emotional states that may lead to more helpful than avoidant behaviors[20].

These results also invite us to consider how emotional and social burdens can alter the pain experienced first-hand. Visualizing the difficulties of a chronically ill person beyond pathophysiological conditions can be a practical exercise. For example, dealing with insufficient resources to face treatment costs, delays in obtaining insurance coverage for admission to a care center, a prolonged time window to start therapy, and establishing a poor level of empathy with the clinical team may trigger affective changes. The literature provides evidence that positive and negative emotions can modulate pain perception. Positive affect tends to inhibit pain, whereas negative affect facilitates it[21]. Solving each situation requires time and effort, can change the emotional state and hope, and most likely contributes to the pain equation. Therefore, this study calls for attention, considering the importance of assessing each patient (as well as related caregivers) beyond the signs and symptoms of pain without ruling out the critical contribution of affective-emotional bidirectional influences.

-

Conclusions

These results demonstrate that pain management should consider sensorial-emotional/affective duality, often ignored, and be aware of the importance of the empathic context in which medical care occurs. The search for a better prognosis in affected patients and a less severe impact on surrounding caregivers is necessary, particularly when a chronic pain condition promotes sustained vicarious interaction that can increase the emotional connection between the actors involved.

Ethics committee approval

The authors declare that they have received approval from the appropriate institutional review board and have followed the ethical principles outlined by the World Medical Association, the Declaration of Helsinki for human experimental investigations, and the International Association for the Study of Pain. Informed consent was obtained from all participants before participation, and their identities were protected throughout.

Submission Statement

This study was not sent to another national or international scientific journal.

Funding

This work was partially supported by the UNIMET Research and Development Directorate attached to the Deanship of Research and Development.

Conflicts of Interest and Copyright Transfer

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest and have transferred the intellectual property rights of the article to the Revista Chilena de Anestesia.

-

References

1. Villarejo-Aguilar L, Zamora-Peña MA, Casado-Ponce G. Sobrecarga y dolor percibido en cuidadoras de ancianos dependientes. Enfermería Global. 2012;11(27):159–64. https://doi.org/10.4321/S1695-61412012000300009.

2. Raja SN, Carr DB, Cohen M, Finnerup NB, Flor H, Gibson S, et al. The revised International Association for the Study of Pain definition of pain: concepts, challenges, and compromises. Pain. 2020 Sep;161(9):1976–82. https://doi.org/10.1097/j.pain.0000000000001939 PMID:32694387

3. Rogero-García J. Las consecuencias del cuidado familiar sobre el cuidador: una valoración compleja y necesaria. Index Enferm. 2010;19(1):47–50. https://doi.org/10.4321/S1132-12962010000100010.

4. Grice-Jackson T, Critchley HD, Banissy MJ, Ward J. Common and distinct neural mechanisms associated with the conscious experience of vicarious pain. Cortex. 2017 Sep;94:152–63. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cortex.2017.06.015 PMID:28759805

5. Giummarra MJ, Fitzgibbon BM, Georgiou-Karistianis N, Beukelman M, Verdejo-Garcia A, Blumberg Z, et al. Affective, sensory and empathic sharing of another’s pain: The Empathy for Pain Scale. Eur J Pain. 2015 Jul;19(6):807–16. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejp.607 PMID:25380353

6. Lawshe CH. A quantitative approach to content validity. Pers Psychol. 1975;28(4):563–75. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-6570.1975.tb01393.x.

7. Tristán-Lopez A. Modification to Lawshe’s quantitative content validity index for an objective instrument. Avances de Medición. 2008;6(1):37–48.

8. Declaration of Helsinki. (2017) https://www.wma.net/es/policies-post/declaracion-de-helsinki-de-la-amm-principios-eticos-para-las-investigaciones-medicas-en-seres-humanos/

9. International Association for the Study of Pain. Ethical guidelines for pain research in humans. 2021. https://www.iasp-pain.org/resources/guidelines/ethical-guidelines-for-pain-research-in-humans/

10. García Campayo J, Rodero B. Aspectos cognitivos y afectivos del dolor. Reumatol Clin. 2009 Aug;5(2 Suppl 2):9–11. Available from: https://www.reumatologiaclinica.org/es-aspectos-cognitivos-afectivos-del-dolor-articulo-S1699258X09001454 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.reuma.2009.03.001 PMID:21794651

11. Decety J. The neurodevelopment of empathy in humans. Dev Neurosci. 2010;32(4):257–67. https://doi.org/10.1159/000317771 PMID:20805682

12. Goubert L, Craig KD, Vervoort T, Morley S, Sullivan MJ, Williams CA, et al. Facing others in pain: the effects of empathy. Pain. 2005 Dec;118(3):285–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pain.2005.10.025 PMID:16289804

13. Bufalari I, Aprile T, Avenanti A, Di Russo F, Aglioti SM. Empathy for pain and touch in the human somatosensory cortex. Cereb Cortex. 2007 Nov;17(11):2553–61. https://doi.org/10.1093/cercor/bhl161 PMID:17205974

14. Reniers RL, Corcoran R, Drake R, Shryane NM, Völlm BA. The QCAE: a Questionnaire of cognitive and affective empathy. J Pers Assess. 2011 Jan;93(1):84–95. https://doi.org/10.1080/00223891.2010.528484 PMID:21184334

15. Singer T, Klimecki OM. Empathy and compassion. Curr Biol. 2014 Sep;24(18):R875–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2014.06.054 PMID:25247366

16. Betti V, Aglioti SM. Dynamic construction of the neural networks underpinning empathy for pain. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2016 Apr;63:191–206. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2016.02.009 PMID:26877105

17. Terrighena EL, Lee TMC. (2017). The neuroimaging of vicarious pain. 2017;411–451). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-48046-6_16..

18. Krishnan A, Woo CW, Chang LJ, Ruzic L, Gu X, López-Solà M, et al. Somatic and vicarious pain are represented by dissociable multivariate brain patterns. eLife. 2016 Jun;5:e15166. https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.15166 PMID:27296895

19. Xu L, Bolt T, Nomi JS, Li J, Zheng X, Fu M, et al. Inter-subject phase synchronization differentiates neural networks underlying physical pain empathy. Soc Cogn Affect Neurosci. 2020 May;15(2):225–33. https://doi.org/10.1093/scan/nsaa025 PMID:32128580

20. Botan V, Bowling NC, Banissy MJ, Critchley H, Ward J. Individual differences in vicarious pain perception linked to heightened socially elicited emotional states. Front Psychol. 2018 Dec;9:2355. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.02355 PMID:30564167

21. Rhudy JL, Dubbert PM, Parker JD, Burke RS, Williams AE. Affective modulation of pain in substance-dependent veterans. Pain Med. 2006;7(6):483–500. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1526-4637.2006.00237.x PMID:17112362

ORCID

ORCID