Cristian Arzola MD, MSc.1, Andrés Merchán-Padilla MD1*, Javiera Paola Vargas MD, MSc.1

Recibido: 13-03-2024

Aceptado: 09-09-2024

©2025 El(los) Autor(es) – Esta publicación es Órgano oficial de la Sociedad de Anestesiología de Chile

Revista Chilena de Anestesia Vol. 54 Núm. 3 pp. 332-334|https://doi.org/10.25237/revchilanestv54n3-18

PDF|ePub|RIS

Importancia del POCUS perioperatorio: Síndrome de Takotsubo

Abstract

We report a case concerning a patient with no previous cardiovascular history, scheduled for a moderately complex gastrointestinal procedure, who presents with a sudden arrhythmia after some time of the anesthetic induction. We describe the sequence of events, the cardiac ultrasound assessment performed intraoperatively and the management provided subsequently. Despite the postoperative diagnosis of stress cardiomyopathy (Takotsubo syndrome)[], the focus of this article is to highlight the importance of anesthesiologists competencies in POCUS[], since the adequate acquisition and interpretation of images can lead to more objective and measured clinical decisions for the benefit of the patient and the end of the health system itself[]-[].

Resumen

Se presenta el caso de una paciente sin antecedentes cardiovasculares, programada para procedimiento gastrointestinal de moderada complejidad, que presenta una arritmia súbita un tiempo después de la inducción anestésica. Se describe la secuencia de eventos, la evaluación ecográfica cardíaca realizada intraoperatoriamente y el manejo brindado posteriormente. A pesar del diagnóstico posoperatorio de miocardiopatía por estrés (síndrome de Takotsubo)[], el objetivo de este artículo es resaltar la importancia de las competencias de los anestesiólogos en POCUS[], ya que la adecuada adquisición e interpretación de imágenes puede llevar a decisiones clínicas más objetivas y mesuradas en beneficio del paciente y del propio sistema de salud[]-[].

-

Clinical case

A58-year-old female patient, with inflammatory bowel disease scheduled for an ileostomy closure. In her past medical history, she did not have any relevant cardiac, respiratory, neurological, endocrine, renal or allergic considerations, except history of fibromyalgia and migraines. At the time, she was not receiving treatment other than lifestyle management. No major complications in previous surgeries regarding anesthesia. However, the patient mentioned having difficulties in a previous surgical event where multiple attempts were needed to obtain an intravenous (IV) access. The patient reports to be physically active, exercise tolerance greater than 4 METs, no previous cardiovascular symptoms: she denies chest pain or tightness, palpitations, shortness of breath or claudication. No other relevant past medical history or symptoms. Patient’s weight and height were 67 kg and 161 cm respectively, and Body Mass Index of 25.8 kg/m2. Vital signs within normal limits (Heart rate: 56 beats per minute (bpm), systolic blood pressure (SBP) 120 mmHg, diastolic blood pressure (DBP) 69 mmHg, pulse oximetry 98% and 16 breaths per minute) and the rest of the physical examination including airway was unremarkable. A preoperative complete blood count was normal, as well as the electrolytes (Na: 133 mmol/L, K: 4.9 mmol/L, Cl: 101 mmol/L) and the serum creatinine (65 mmol/L). In an ECG 5 months before the event, the rhythm was sinus, regular, without signs of ischemia or necrosis, with a QT interval of 0.44, with no alterations.

After the preoperative interview including verbal informed consent and safety checklist, an ultrasound assisted IV access with a 20G catheter was obtained in a single attempt in the left forearm. Standard Canadian Anesthesiologists Society monitoring was initiated .Intravenous anesthesia induction was conducted as follows: 100 mg lidocaine 2%, 250 mcg fentanyl, 150 mg propofol, 30 mg rocuronium and 8 mg dexamethasone. The airway was secured with a #7.0 size regular Endotracheal tube (ETT) in a single attempt direct laryngoscopy with a Mac 3 blade and the tube was taped at 21 cm from the lips. ETT placement confirmation was done through capnography and bilateral chest auscultation. Anesthesia maintenance was initiated with sevoflurane at values between 0.9 and 1.1 MAC. At 7 minutes after intubation, the patient presented with severe sinus bradycardia reaching at the lowest rate of 27 bpm and 0.4 mg of glycopyrrolate were rapidly administered. One minute after this, a single episode of monomorphic non-sustained ventricular tachycardia was observed in the monitor, reaching 120 bpm for approximately 25 seconds, followed by high blood pressure values between 210-160 for systolic blood pressure and 140-118 for diastolic pressure for 5 minutes. It should be noted that this episode occurs before the start of the surgical stimulus. An attempt was made to optimize the anesthetic depth by administering an additional bolus of Propofol, and it was verified a sevoflurane MAC of 0.9. In the following minutes the heart rate returned to normal and the blood pressure decreased progressively and remained in normal limits for the rest of the case (around one hour) without the need of using any vasopressor or inotropic medication.

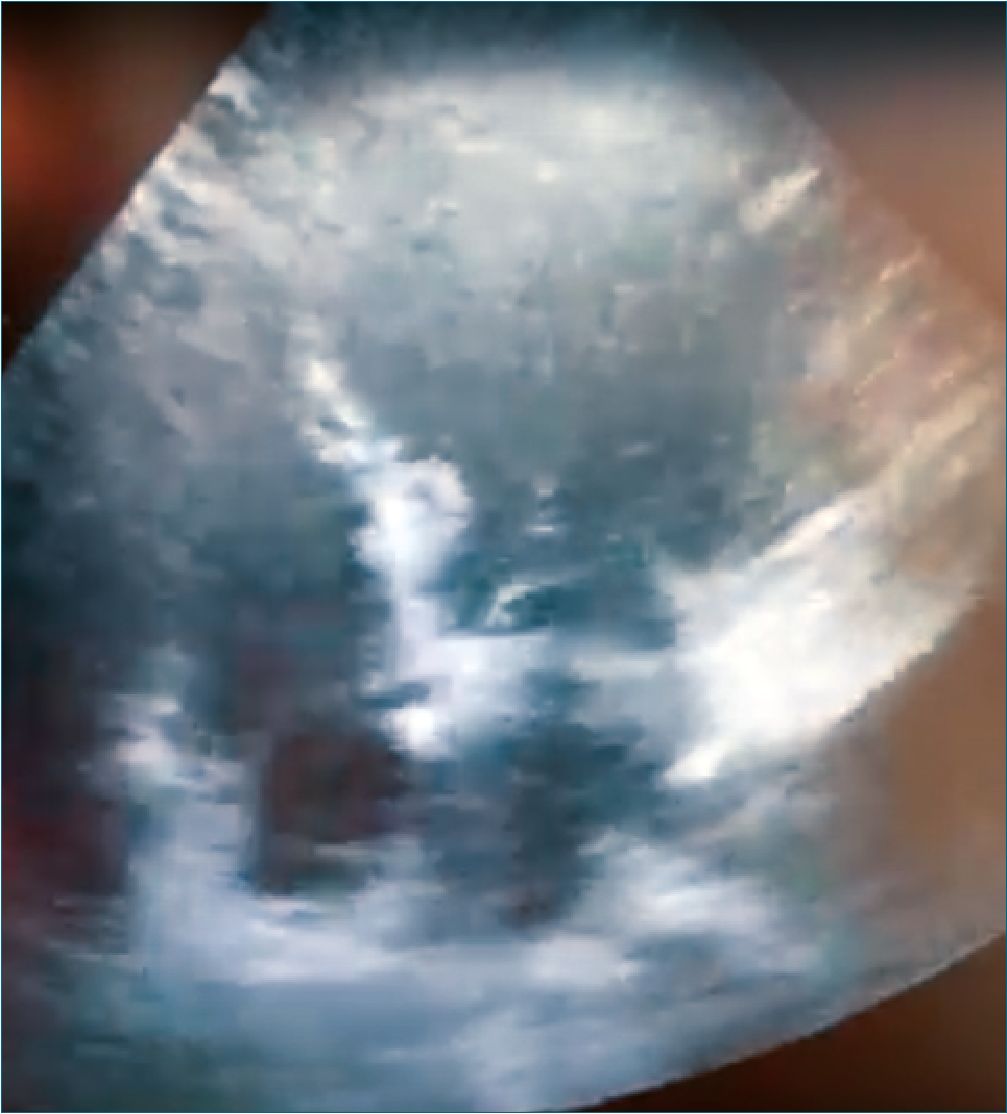

A transthoracic echocardiography was performed intraoperatively within 10 minutes after the dysrhythmia episode. In the 4-chamber view, generalized hypokinesis of the left ventricle (LV) with mild to moderate bulging was observed. Because the patient was undergoing surgery, it was not possible to obtain images from other views. It is worth highlighting that after the self-limited episode of arrhythmia, the patient’s clinical condition was stable. However, when considering the findings of the point of care echocardiogram, it was decided to extend the study by requesting troponins, evaluation by cardiology and a formal echocardiogram. At the end of the procedure, the patient was extubated and transferred to the post-anesthesia care unit, from where she was transferred to the ward, remaining stable and asymptomatic during this period and the rest of her hospital stay.

The following day after the cardiology assessment, a transthoracic echocardiogram was performed showing a mildly reduced LV ejection fraction (54%). The distal half of the LV was hypokinetic and there was compensatory hypercontractility of the basal segments. The pattern was suggestive of stress cardiomyopathy, (Figure 1) although left anterior descending artery (LAD) territory infarction could not be completely ruled out. Also, no significant valvular abnormalities. The Troponin T curve: Postoperative day (POD) 0: 258 ng/L, POD 1: 145 ng/L, POD 4: 27 ng/L. The report for the follow-up echocardiogram on POD 4 was: Normal left ventricular size and minimally reduced global systolic dysfunction (LVEF 53% by Simpson’s). Compared to previous TTE, it was described improvement in the stress cardiomyopathy. Cardiology indicated a coronary angiography for which the patient decided to be followed by her family doctor. She was discharged after a satisfactory postoperative course at POD 5.

Figure 1.

-

Discussion

The increasing popularity of the use of POCUS in the perioperative setting is well deserved(5). Its low cost, wide availability, and excellent safety profile have made it an invaluable tool among anesthesiologists[6]. In this context applications include airway[7], gastric[8], pulmonary evaluation[9), vascular access, regional anesthesia, cerebral perfusion and the list con- tinues[2],[10].

Specifically for the scenario presented in this clinical case, cardiac POCUS was presented as a tool that allowed us to rule out acute conditions that require specific treatment: cardiac tamponade, pulmonary thromboembolism, valvular abnormalities, ischemia, intravascular volume[11] among others. It is clear that the compounded information obtained from the intraoperative cardiac POCUS and clinical behaviour (wall motion abnormalities, moderate bulging of the left ventricle, in the absence of hypotension or changes on the EKG) allowed the clinician to conduct the proper decision-making and follow-up in the postoperative period. Worth noting, a patient with profound intraoperative hypotension secondary to acute ischemia may not show changes in the EKG but cardiac ultrasound would demonstrate hypokinesis or akinesia of the walls, contributing to the diagnosis[12].

Point-of-care ultrasound is a useful tool not only in cardiac patients but also in patients with not known formal cardiac risk factor presenting with intraoperative cardiac and hemodynamic events. Depression is a risk factor for stress cardiomyopathy[13], and also fibromyalgia could be associated given the hypothesis of high catecholamine levels in response to emotional stress and a greater cardiac sensitivity to endogenous catecholamine stimulation[14]. However, these medical conditions do not lead to pursue cardiac assessments or further monitorization during an elective surgery due to the consideration of low risk.

According to International Takotsubo diagnostic criteria[15], patients show transient left ventricular dysfunction presenting as apical ballooning or wall motion abnormalities, new EKG abnormalities (St-segment elevation, ST-segment depression, T-wave inversion) or in rare cases bradycardia or ventricular arrythmias as in this case and levels of biomarkers are moderately elevated. Despite the transient nature of this condition, the traditional concept of being benign may underestimate the risk of in-hospital complications[16],[17] and long-lasting subclinical cardiac dysfunction[18]. Depending on the stress factor, Takotsubo patients related to physical stress showed higher mortality rates than acute coronary syndrome patients during long-term follow-up[19]. In a cohort of 519 patients with a confirmed diagnosis of takotsubo syndrome the recurrency was 7.5% and 16.2% died in a follow up of 5.2 years[20].

In the present case with the intraoperative events and in the absence of the bedside cardiac ultrasound, the patient could have missed the proper follow up by cardiology, troponins and the further risk stratification. We believe that widespread learning of POCUS in the field of anesthesiology and the judicious, goal-directed and structured use[21],[22] of cardiac ultrasound (and other modalities) leads to more accurate decision making-based on more complete information about the patient’s situation in perioperative period. The use of bedside cardiac Ultrasound could add information to do a proper screening, follow-up, and management in patients with an unexpected cardiac event that has a potential long-term impact like the one presented in this case report.

Conflicts of interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Funding: The authors have no sources of funding to declare for this manuscript.

-

References

1. López Libano J, Alomar Lladó L, Zarraga López L. The Takotsubo Syndrome: Clinical Diagnosis Using POCUS. POCUS J. 2022 Apr;7(1):137–9. PMID:36896282

2. Li L, Yong RJ, Kaye AD, Urman RD. Perioperative Point of Care Ultrasound (POCUS) for Anesthesiologists: an Overview. Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2020 Mar;24(5):20. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11916-020-0847-0 PMID:32200432

3. De Marchi L, Meineri M. POCUS in perioperative medicine: a North American perspective. Crit Ultrasound J. 2017 Oct;9(1):19. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13089-017-0075-y PMID:28993991

4. Meier I, Vogt AP, Meineri M, Kaiser HA, Luedi MM, Braun M. Point-of-care ultrasound in the preoperative setting. Best Pract Res Clin Anaesthesiol. 2020 Jun;34(2):315–24. PMID:32711837

5. Moore CL, Copel JA. Point-of-care ultrasonography. N Engl J Med. 2011 Feb;364(8):749–57. PMID:21345104

6. Kendall JL, Hoffenberg SR, Smith RS. History of emergency and critical care ultrasound: the evolution of a new imaging paradigm. Crit Care Med. 2007 May;35(5 Suppl):S126–30. PMID:17446770

7. You-Ten KE, Siddiqui N, Teoh WH, Kristensen MS. Point-of-care ultrasound (POCUS) of the upper airway. Can J Anaesth. 2018 Apr;65(4):473–84. PMID:29349733

8. Perlas A, Arzola C, Van de Putte P. Point-of-care gastric ultrasound and aspiration risk assessment: a narrative review. Can J Anaesth. 2018 Apr;65(4):437–48. PMID:29230709

9. Taylor A, Anjum F, O’Rourke MC. Thoracic and Lung Ultrasound. StatPearls [Internet]Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2023.[ [cited 2023 Nov 2]], Available from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK500013/

10. Naji A, Chappidi M, Ahmed A, Monga A, Sanders J. Perioperative Point-of-Care Ultrasound Use by Anesthesiologists. Cureus. 2021 May;13(5):e15217. PMID:34178536

11. ASRA [Internet]. [cited 2023 Nov 2]. POCUS Spotlight: Perioperative Hemodynamic Assessment in Noncardiac Surgery. Available from: https://www.asra.com/news-publications/asra-newsletter/newsletter-item/asra-news/2022/11/01/pocus-spotlight-perioperative-hemodynamic-assessment-in-noncardiac-surgery

12. Augoustides JG, Hosalkar HH, Savino JS. Utility of transthoracic echocardiography in diagnosis and treatment of cardiogenic shock during noncardiac surgery. J Clin Anesth. 2005 Sep;17(6):488–9. PMID:16171674

13. Dias A, Franco E, Figueredo VM, Hebert K, Quevedo HC. Occurrence of Takotsubo cardiomyopathy and use of antidepressants. Int J Cardiol. 2014 Jun;174(2):433–6. PMID:24768456

14. Ziegelstein RC. Depression and tako-tsubo cardiomyopathy. Am J Cardiol. 2010 Jan;105(2):281–2. PMID:20102933

15. Ghadri JR, Wittstein IS, Prasad A, Sharkey S, Dote K, Akashi YJ, et al. International Expert Consensus Document on Takotsubo Syndrome (Part I): Clinical Characteristics, Diagnostic Criteria, and Pathophysiology. Eur Heart J. 2018 Jun;39(22):2032–46. PMID:29850871

16. Gianni M, Dentali F, Grandi AM, Sumner G, Hiralal R, Lonn E. Apical ballooning syndrome or takotsubo cardiomyopathy: a systematic review. Eur Heart J. 2006 Jul;27(13):1523–9. PMID:16720686

17. Assad J, Femia G, Pender P, Badie T, Rajaratnam R. Takotsubo Syndrome: A Review of Presentation, Diagnosis and Management. Clin Med Insights Cardiol. 2022 Jan;16:11795468211065782. PMID:35002350

18. Scally C, Rudd A, Mezincescu A, Wilson H, Srivanasan J, Horgan G, et al. Persistent Long-Term Structural, Functional, and Metabolic Changes After Stress-Induced (Takotsubo) Cardiomyopathy. Circulation. 2018 Mar;137(10):1039–48. PMID:29128863

19. Ghadri JR, Kato K, Cammann VL, Gili S, Jurisic S, Di Vece D, et al. Long-Term Prognosis of Patients With Takotsubo Syndrome. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018 Aug;72(8):874–82. PMID:30115226

20. Lau C, Chiu S, Nayak R, Lin B, Lee MS. Survival and risk of recurrence of takotsubo syndrome. Heart. 2021 Jul;107(14):1160–6. https://doi.org/10.1136/heartjnl-2020-318028 PMID:33419884

21. Kruisselbrink R, Chan V, Cibinel GA, Abrahamson S, Goffi A. I-AIM (Indication, Acquisition, Interpretation, Medical Decision-making) Framework for Point of Care Lung Ultrasound. Anesthesiology. 2017 Sep;127(3):568–82. PMID:28742530

22. Soni N, Kory P, Arntfield R. Point-of-care Ultrasound. 2nd ed. 2019.

ORCID

ORCID