Midhun K. A.1, Neelam Prasad1* Priyanka Singh1, Munisha Agarwal1

Recibido: 15-03-2025

Aceptado: 12-04-2025

©2025 El(los) Autor(es) – Esta publicación es Órgano oficial de la Sociedad de Anestesiología de Chile

Revista Chilena de Anestesia Vol. 54 Núm. 5 pp. 662-669|https://doi.org/10.25237/revchilanestv54n5-23

PDF|ePub|RIS

Comparación de un nuevo dispositivo tecnológico de información con dexmedetomidina intranasal para aliviar la ansiedad preoperatoria en niños

Abstract

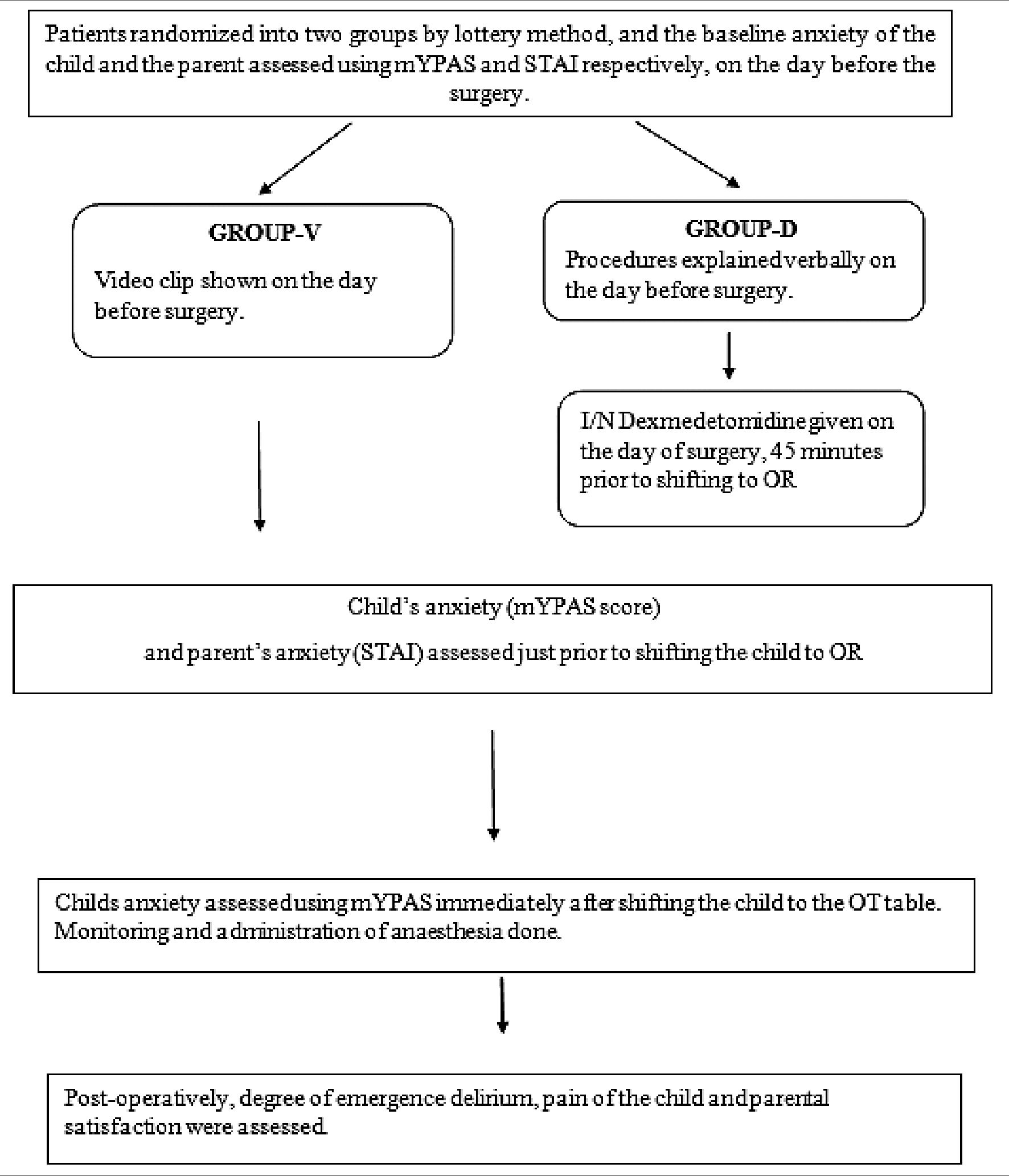

Introduction: Various non-pharmacological interventions are being used to reduce preoperative anxiety in children. Technology-based preoperative preparatory programs have been recently explored and practiced. Dexmedetomidine, one of the many pharmacological agents used to allay anxiety, provides sedation, anxiolysis and analgesic effects without causing respiratory depression. Objetive: This study aimed to evaluate and compare the efficacy of preoperative newer information technology Devices (NITDs) in the form of a pre-procedure informative video clip with intranasal Dexmedetomidine to allay preoperative anxiety in the pediatric population. Material and Methods: 117 children aged 6-11 years were randomly allocated into two groups. Group-V who were shown a video in which clown physicians explained and acquainted the children with the anaesthesia procedure and equipments in the operating room (OR) in a funny manner. Group-D was given intranasal dexmedetomidine 45 minutes before shifting to OR. Anxiety was assessed on the day before surgery(T1), in the preoperative holding area(T2) and immediately after shifting to OT table(T3). Results: The anxiety scores in T2 and T3 were significantly lower in group-V compared to group-D. The median pain score and requirement of rescue analgesia were significantly higher in the group V compared to group D. There was no statistically significant difference in the incidence of emergence delirium, parental anxiety and parental satisfaction between the two groups. Conclusion: The use of NITDs in the form of pre-procedure informative video clip is more effective than pharmacological methods in reducing preoperative anxiety in children. Although, postoperative pain control was superior in children receiving dexmedetomidine.

Resumen

Introducción: Se están utilizando diversas intervenciones no farmacológicas para reducir la ansiedad posoparatoria en los niños. Los programas de preparación preoperatoria basados en tecnologías han sido recientemente explorados y practicados. La dexmedetomidina, uno de los muchos agentes farmacológicos utilizados para aliviar la ansiedad proporciona sedación, ansiolisis y analgesia, sin causar depresión respiratoria. Objetivo: Este estudio tuvo como objetivo evaluar y comparar la eficacia de lso nuevos dispositivos de tecnología de la información (NTIDs) en forma de un video informativo preprocedimiento con dexmedetomidina intranasal para aliviar la ansiedad preoperatoria en población pediátrica. Materiales y Métodos: 117 niños entre 6 a 11 años fueron asignados aleatoriamente en dos grupos. Grupo -V a quienes se les mostró un video en que los médicos payasos explicaban y familiarizaban a los niños con el procedimiento de anestesia y los equipos en la sala de operaciones de manera divertida. Y el grupo -D se le administró dexmedetomidina intranasal 45 minutos antes de trasladarse al quirófano. La ansiedad se evaluó el día antes de la cirugía (T1), en el área de espera del preoperatorio (T2) e inmediatamente después de trasladarse a la mesa de operaciones. Resultados: Las puntuaciones de ansiedad en T2 y T3 fueron significativamente más bajas en el grupo -V en comparación con el grupo -D. No hubo diferencia estadísticamente significativa en la incidencia de delirio, ansiedad parental y satisfacción parental entre los dos grupos. Conclusión: El uso de NlTDs en forma de video informativo previo al procedimiento es más efectivo que los métodos farmacológicos para reducir la ansiedad preoperatoria en los niños. Sin embargo, el control del dolor posoperatorio fue superior en los niños que recibieron dexmedetomidina.

-

Introduction

Preoperative anxiety regarding impending surgical experience is a common phenomenon in paediatric patients that has been associated with a number of negative effects before, during and after the surgery. Before surgery, it may cause agitation, crying, spontaneous urination, and the need for physical restraint during anaesthetic induction. Postoperatively, it may cause increased pain sensation, sleeping disturbances, parent-child conflict, and separation anxiety[1].

There are various pharmacological and non-pharmacological interventions to alleviate preoperative anxiety in children. Pharmacological agents like Midazolam, Clonidine, Fentanyl and dexmedetomidine have been used as sedative to allay anxiety. Dexmedetomidine is a selective a-2 adrenoceptor agonist that provides sedation, anxiolysis and analgesic effects without causing respiratory depression[2],[3]. It is increasingly used intranasally for premedication where it has a bioavailability of 80%. A dose of 1 to 2 pg/kg is usually used for intranasal premedication, taking 30-40 minutes for peak effect[4].

Nowadays, there is great motivation towards non-pharmacological interventions including verbal distraction, hospital clowns, music therapy, and newer information technology devices like informative pre-hospital tour, handheld audio-visuals, video games, web or internet based preparatory programs, etc. Recently newer information technology devices (NITDs) are being used to deliver pre-procedure information to patients to decrease their anxiety. Most of the trials regarding non-pharmacological interventions were conducted in high-income countries, indicating a high risk of bias[5]. A large population of children in the middle- and low-income countries are unfamiliar with the new computer gadgets and cartoons characters. Very limited literature is available to compare the efficacy of pharmacological and various non-pharmacological interventions, especially those using newer information technology devices. Hence, the study was planned to assess and compare the efficacy of the use of NITDs in the form of a 6 minutes pre-procedure informative video clip with intranasal Dexmedetomidine as a tool to alleviate anxiety in pediatric patients with the hypothesis that the two methods were comparable.

-

Materials and Methods

The study was a randomized comparative study conducted over a period of one year, after taking Institutional Ethics Committee approval (F.No.17/IEC/MAMC/2018/08). 117 Children of either sex of 6-11 years of age of American Society of Anaesthesiology (ASA) physical health status I & II, scheduled to undergo elective surgery under general anesthesia were enrolled. Children with known cognitive disabilities, language barriers, developmental disabilities, known allergy or hypersensitivity to dexmedetomidine, acute or chronic nasal trauma or nasal deformity and those taking psychiatric medications were excluded from the study.

Primary outcome of the study was to assess the pre-operative anxiety of the child immediately after shifting the child to the operating room. The secondary outcomes assessed were pre-operative anxiety of the child in the evening before the day of surgery and just before shifting the child to the operating room from the pre-operative holding area, anxiety level of the parents, degree of emergence delirium, post-operative pain and parental satisfaction after the surgery.

The sample size was calculated based on a previous study by Liguori et al6 considering anticipated Anxiety score in two groups as primary variable. With an 80% power and an alpha level of 0.05, the sample size was calculated using the appropriate formula and was decided to be 55 in each group. The enrolled patients were assigned to one of the two groups by randomization using sealed envelope lottery method into group V and group D.

In the evening before the day of surgery, each child and their parents were assessed for pre-operative anxiety using modified Yale Pre-operative Anxiety Scale (mYPAS) and StateTrait Anxiety Inventory (STAI) scale respectively by the anaesthesiologist (A1)[8].

The children in group V were shown a video by another anaesthesiologist (A2) who was not involved in taking observations, in the presence of the parent/guardian. This video runs for 6 minutes in which two clown physicians take a pre-hospital tour and give details of the equipments and procedures inside the operating room in a funny and playful manner. This video

was prepared prior to the study period and was validated by anaesthesia consultants. Once the video ends, the child and the parent were free to ask questions about anaesthesia and surgical procedures. Child was free to stop or interrupt the video in between at any time. Children who refused to watch the video or who did not watch the whole video were excluded from the study.

* (link to the video: https://drive.google.com/file/d/1FoFDm- pOvbfvV9I9Boo_XJT942j4Jpw7/view?usp=drivesdk)

In Group D, anaesthesiologist (A2) verbally explained about the anaesthetic procedures on the evening before the surgery and asked the child and the parent for queries regarding the anaesthesia or surgical procedures.

Preoperatively all children followed standard NPO guidelines and did not receive any pre-medication or any analgesic drug. All the children were accompanied by their parents in pre operative area.

In Group D, standard monitors were attached and the baseline hemodynamic parameters were assessed in the preoperative holding area (T2). The anaesthesiologist (A2) who was not involved in making observations administered intranasal Dexmedetomidine at a dose of 1microgram per kg to these children by simply dripping the drug into both nostrils from a 1-ml insulin syringe.on the lap of mother with head up position. After 45 minutes, hemodynamic parameters were again recorded.

Pre-operative anxiety was assessed by the anaesthesiologist (A1) who was blinded regarding the group allocation, using mYPAS just before shifting them to the operating room (which is 45 minutes after instillation of the drug in group D). Also, the observer evaluated the parents for preoperative anxiety using STAI just before transfering the patient to the OR.

After being received in Pre operative holding area all pt were transferred to the OR not accompanied by their parents, as our hospital policy. Anxiety of the patient was assessed using mYPAS (T3) after shifting the child to the operating room. Standard monitoring and standard protocols for General anaesthesia (intravenous/ inhalation induction) were followed for all the patients.

Post-operatively, degree of emergence delirium was recorded immediately after extubation in OR using PAED scale[9]. In the postoperative room, pain of the child was assessed using Face Pain Scale-Revised (FPS-R)[10]. All the observations were recorded by anaesthesiologist (A1). Whenever the FPS-R showed a score of 2 or more, intravenous Fentanyl was administered at a dose of 1 microgram per kilogram. Pain assessment was done in post anaesthetic care unit (PACU) till one after surgery. On the day following the surgery, post-operative parental satisfaction was assessed using Visual Analogue scale (VAS) score.

Statistical analysis

Statistical testing was conducted with the statistical package for the social science system version SPSS 25.0. Continuous variables were presented as mean ± SD if the data was normally distributed or median (IQR) if the data was non-normally distributed. The comparison of continuous variables between the groups were performed using Student’s t test. Nominal categorical data between the groups were compared using Chi- squared test or Fisher’s Exact test as appropriate. Non-normal distribution continuous variables were compared using Mann Whitney U test. For all statistical tests, a p value less than 0.05 was taken to indicate a significant difference.

*Still from the video clip showing two clown physicians.

-

Results

The two groups were comparable in terms of socio-demographic and anthropometric parameters of the patients and the type of surgeries they underwent. Children undergoing eye, ENT, urogenital and abdominal surgeries were included, out of which majority of cases included were for eye surgery (37 and 32 children in group D and V respectively). Parents of majority of the patients in both the groups had primary schooling as their educational status and the two groups were statistically significant (p value 0.596).

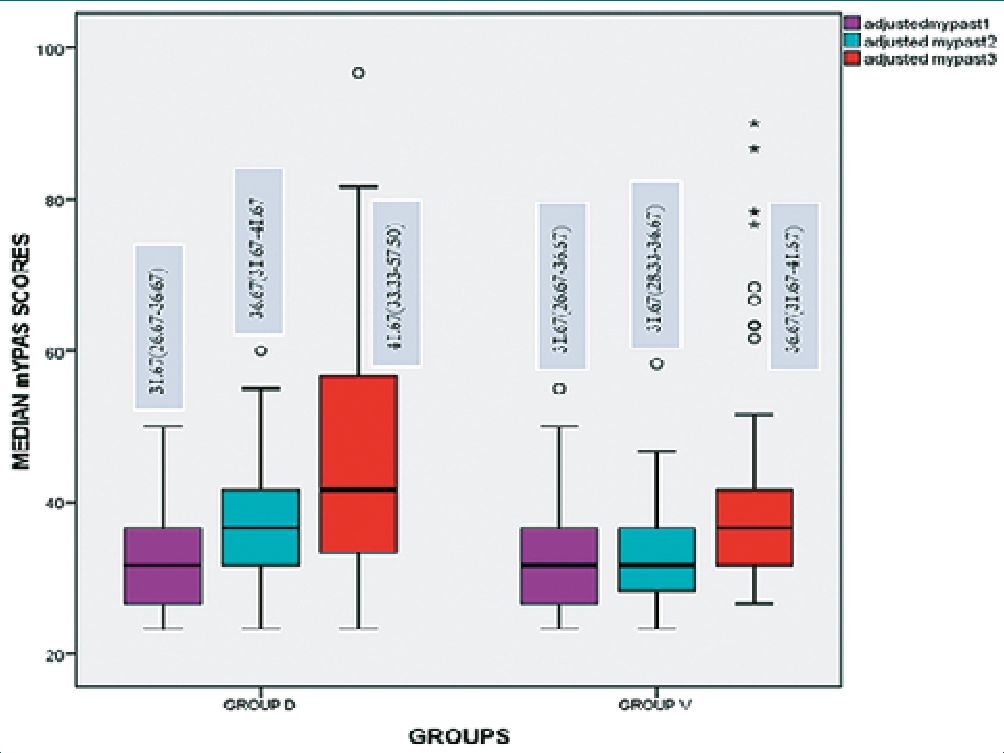

On the evening before the day of surgery (T1), the median score of anxiety using mYPAS for both groups were 31.67 with interquartile range (IQR) of 26.67-36.67 and was statistically comparable between the groups (p value 0.982), showing that the preoperative anxiety in both the groups, before any interventions on the day before surgery was not statistically different. After the two interventions, at T2, that is just before transferring the child to operating room, anxiety median scores were increased to 36.67 with IQR of 31.67-41.67 in group D and remained same as 31.67 with IQR of 26.67-36.67 in group V and was found to be statistically significant (p value 0.016). At T3, the median anxiety score increased further to 41.67 with IQR of 33.33-57.50 in Group D and 36.67 with IQR of 31.6741.67 in Group V and there was significant statistical difference between the two groups, showing that patients in Group V had lower anxiety scores than those in Group D on the operation theatre table (Table 1, Figure1).

The anxiety of the parents of the patients was assessed using STAI score at two times. In both the groups, there was statistically significant increase in the median anxiety scores of the parents from T1 to T2 (Table 2). But there was no statistically significant difference between the anxiety scores of the parents between group V and group D at both T1 and T2.

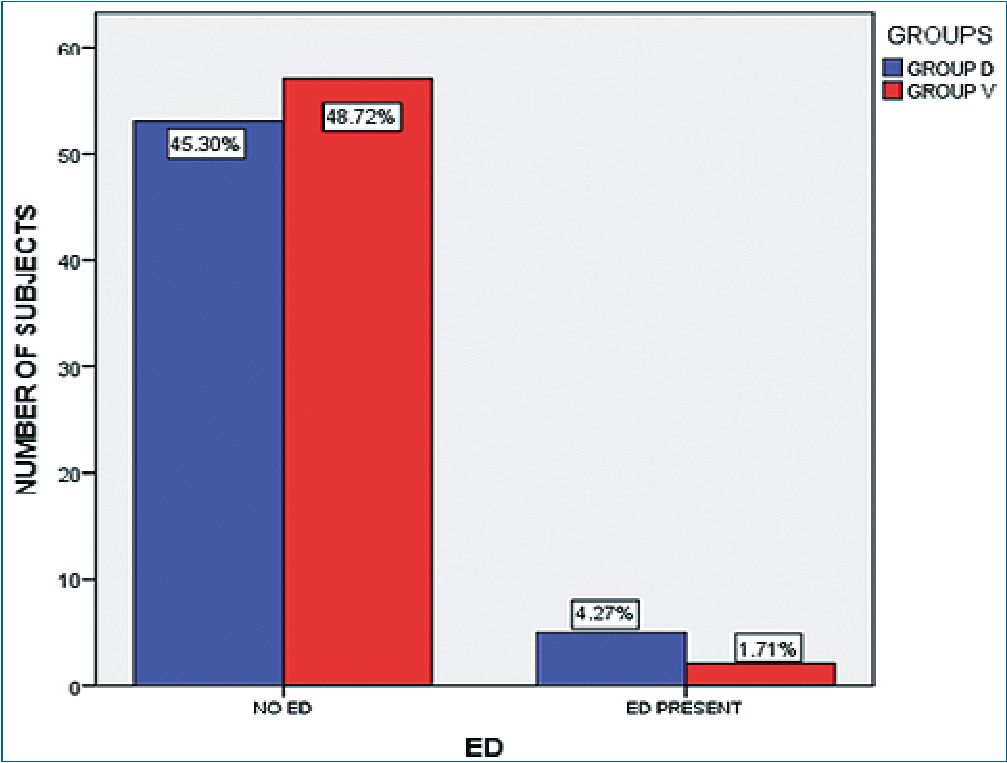

PAED scale was used to assess emergence delirium immediately after the surgery. Patients with a score of > 12 was considered to have emergence delirium. Out of the total patients, only 6% were found to have emergence delirium of which 4.3% were in group D and 1.7% were in group V and the occurrence was statistically comparable between the two groups (Table 3).

Post-operative pain score of the patients were assessed using Faces Pain Scale- Revised (FPS-R). The median score in group V was 4 (IQR of 2-8) and group D was 2 (IQR of 2-4), difference being statistically significant (p value of 0.01) (Table 4).

The median VAS score for parental satisfaction was 9 in both the groups with an IQR of 8-9 which was statistically insignificant (p value 0.248).

-

Discussion

It is important to consider the age of the child while using various behavioural interventions because preoperative anxiety manifests in age-specific ways based on the developmental stage; very young children (1-3 years old) may experience separation anxiety from their parents and familiar home. Somewhat older children (4-6 years old) fear surgery. Older children and adolescents may fear awakening during surgery and the possibility of not recovering from anaesthesia[11]. Children with age around 6 to 11 years develop the abilities to think logically and can generalize information from one experience to another[12]. Also, Children around this age group can express their own information needs when approached in a sensitive manner[13]. Hence, we decided to enroll children of 6 to 11 years in our study.

Table 1. Median values of anxiety scores of the two groups

|

Time of Assessment* |

Groups |

p value |

||

|

Group D |

Group V |

|||

|

Median (IQR) |

Median (IQR) |

|||

|

T1 |

31.67 (26.67 – 36.67) |

31.67 (26.67 – 36.67) |

0.812 |

|

|

T2 |

36.67 (31.67 – 41.67) |

31.67 (28.33 – 36.67) |

0.016 |

|

|

T3 |

41.67 (33.33 – 57.50) |

36.67 (31.67 – 41.67) |

0.006 |

Table 2. Comparison of parental anxiety (Inter Group)

|

Time of Assessment* |

Groups |

p value |

|

|

Group V |

Group D |

||

|

Median (IQR) |

Median (IQR) |

||

|

T1 |

11 (10 – 12) |

11 (10 – 12) |

0.372 |

|

T2 |

12 (11 – 13) |

12 (11 – 13) |

0.962 |

Table 3. Comparison of degree of emergence delirium

|

Emergence delirium |

Groups |

Total |

p value |

|

|

Group D n (%) |

Group V n (%) |

|||

|

Present |

5 (4.3) |

2 (1.7) |

7 (6.0) |

|

|

Absent |

53 (45.3) |

57 (48.7) |

110 (94.0) |

0.272 |

|

Total |

58 (49.6) |

59 (50.4) |

117 (100) |

|

Figure 1. Median values of anxiety scores of the two groups.

Figure 2. Comparison of degree of emergence delirium (p value- 0.272).

Table 4. Median values of post-operative pain scores

|

Groups |

Post-operative pain scores |

p value |

|

Median (IQR) |

||

|

Group V |

4 (2-8) |

0.016 |

|

Group D |

2 (2-4) |

This study was conducted to assess the pre-operative anxiety of the child immediately after shifting the child to the operation theatre table, for which we used mYPAS tool, which is a validated scoring system for anxiety assessment. Inside the operating room, the median anxiety score (T3) was 41.67 with an IQR of 33.33-57.50 (group D) and 36.67 with an IQR of 31.67-41.67 (group V), the difference being statistically significant (p value 0.006). This might be because the children in group V were already accustomed to the environment and the equipments inside the operating room since they were shown the informative video a day prior to the surgery.

Our study observed that the median anxiety scores a day prior to the surgery (T1) were statistically comparable (p value 0.812) between group D and group V. This might be because this anxiety score was assessed when the children were in a comfortable and pleasant environment with their parents in the pre-operative ward and no interventions has been done on them.

The median anxiety scores just before transferring to OR (T2) was observed to be significantly more in group D compared to group V (p value 0.016). This is the time when the child is being separated from their parents. Parental separation itself can be stressful for the child and may cause confusion and anxiety[14]. The significant decreased median anxiety scores in group V at this time might be because, even though there was parental separation at this time, since the children were exposed to the informative video, so they were already adapted to this situation.

In a similar study conducted by Stefano Liguori et al in Italy, they created an app called Clickamico, that shows a 6 minutes videoclip of clown physicians giving a comical and informative tour of the operating room. The study observed that the application was effective in reducing preoperative anxiety in children of 6 to 11 years of age before shifting them to the operating room. But in this study, anxiety score was not assessed after shifting the children to the operating room[6].

Sara Fernandes et al., in a study, used a multimedia application called “An Adventure at the Hospital” with the goal of preparing children for common outpatient surgeries and compared it with an entertainment video game group in which children played popular retail video games and a control group without any interventions. Children’s preoperative worries were assessed using Child Surgery Worries Questionnaire self-reporting measure which is a Likert scale and The Self-Assessment Manikin. It was observed that the children who received the educational multimedia intervention reported lower level of worries about hospitalization, medical procedures, illness and negative consequences, compared to the other groups[15].

Another study by Lakshman K. et al., concluded that multimedia-based educational video showing technique of spinal anaesthesia significantly reduces anxiety and associated haemodynamic variations in oncosurgery patients undergoing spinal anaesthesia and is an easy way for transfer of information about anaesthesia which allows time for patients to reflect on this preoperatively, thereby reduces their anxiety[16].

But unlike our study, these studies did not compare the non-pharmacological interventions with a pharmacological intervention.

Another study by Samuel C. Seiden et al., to compare the effects of a tablet-based interactive distraction (TBID) tool to oral midazolam on perioperative anxiety concluded that tablet-based interactive distraction is superior to oral midazolam in minimizing anxiety in children aged 1-11 years[17]. Even though this study compared technology-based intervention with a pharmacological intervention, they used a distraction technique rather than providing pre-procedure information to the children.

Recently, a systemic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials on the efficacy of various distraction techniques by Mustafa MS et al.[18], concluded that video distraction is a prevalent distraction tool applied across numerous studies that included cartoons, relaxation-guided imagery, and self-produced audiovisual presentations and were found to be effective tools for curbing preoperative anxiety. The nonpharmacological distraction techniques included in study were Virtual reality, Psychological Preparation, Entertainment Videos, Videogames, Books, Music, Clown Intervention, Guided Tour, and Smartphone and Tablet.

Another parameter assessed in our study was the parental anxiety assessed using STAI and no significant differences were observed at both T1 and T2 between group V and group D (p0.372 for T1 and p-0.962 for T2). A previous study conducted by Joseph F et al observed significant decrease in anxiety of the parents after they were shown a 22 minutes pre-anaesthetic educational videotape[19].

But these studies used videos that focus to deliver accurate information regarding the perioperative events to the parents, while our study used a video that delivers the information in a semi-fantasy manner targeting mainly the children. So, in order to decrease anxiety of the parents, pre-procedure informative video needs to be prepared such that it delivers all the accurate informations in detail regarding the procedures that their children are going to undergo inside the OR.

The incidence of emergence delirium, assessed using PAED scale, was comparable between the two groups. A similar study conducted by Jung-Hee Ryu et al tested the effect of an immersive virtual reality tour of the operating theatre on emergence delirium in children. The study observed that even though the virtual reality tour was effective in alleviating preoperative anxiety in children, it did not reduce the incidence and severity of emergence delirium[20].

When the two groups were compared for postoperative pain, the median FPS-R score and requirement of rescue analgesia were significantly more in the video group compared to Dexmedetomidine group (p -0.016). This is in accordance with another study conducted by Aynur Akin et al., which compared intranasal Midazolam with intranasal Dexmedetomidine for premedication in children and found that the number of children requiring postoperative analgesia was lower in the dexmedetomidine group[21].

Another outcome of our study was parental satisfaction after the procedure, and there was no statistically significant difference between the two groups (p -0.248). This might be because, in addition to the preoperative anxiety of their children, parental satisfaction is also influenced by other factors like the amount of information they had obtained from their

doctors regarding the treatment and the procedure, the fasting time of the children, the nursing care provided by the staff, the waiting time and the waiting room environment[22].

-

Limitations of the study

• Only those children admitted for elective procedures were enrolled in the study. Since the video intervention was done a day before the surgery, it is difficult to use it in emergency setup.

• For decreasing parental anxiety, a video that focus to deliver accurate information regarding the perioperative events to the parents should have been used.

-

Conclusion

Hence, we conclude that NITDs based behavioural intervention in the form of a preoperative informative video clip was found to be more effective in reducing preoperative anxiety in children between 6 and 11 years of age than intranasal dexmedetomidine. Replacing pharmacological interventions with newer information technology-based methods can avoid the adverse side effects of the drugs and can enhance recovery following anaesthesia. Although, limitation of the study was that only those children admitted for elective procedures were enrolled in the study. Since the video intervention was done a day before the surgery, it is difficult to use it in emergency setup. Also, for decreasing parental anxiety, a video that focus to deliver accurate information regarding the perioperative events to the parents should have been used.

Acknowledgments: Financial and material support – None.

Authors’contributions

A1 – Acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data for the work and the anesthetic management of the patient and writing of the draft of the manuscript.

A2 – Substantial contributions to the conception or design of the work; Agreement to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved was responsible for the anesthetic management of the patient and helped write the manuscript.

A3 – Drafting the work or revising it critically for important intellectual content.

A4- Supervision and final approval of the version to be published.

The manuscript has been read and approved by all the authors, the requirements for authorship as stated earlier in this document have been met, and each author believes that the manuscript represents honest work.

Conflict of interest statement: No conflict of interest declared.

Funding-No funding: Ethics approval and consent to participate-Taken.

Consent for publication-taken.

Competing interests: The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Permission for open access: yes.

Clinical trial registration: CTRI/2019/05/019135

-

References

1. Wright KD, Stewart SH, Finley GA, Buffett-Jerrott SE. Prevention and intervention strategies to alleviate preoperative anxiety in children: a critical review. Behav Modif. 2007 Jan;31(1):52–79. https://doi.org/10.1177/0145445506295055 PMID:17179531

2. Yuen VM, Hui TW, Irwin MG, Yao TJ, Chan L, Wong GL, et al. A randomised comparison of two intranasal dexmedetomidine doses for premedication in children. Anaesthesia. 2012 Nov;67(11):1210–6. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2044.2012.07309.x PMID:22950484

3. Yuen VM, Hui TW, Irwin MG, Yuen MK. A comparison of intranasal dexmedetomidine and oral midazolam for premedication in pediatric anesthesia: a double-blinded randomized controlled trial. Anesth Analg. 2008 Jun;106(6):1715–21. https://doi.org/10.1213/ane.0b013e31816c8929 PMID:18499600

4. Chapter 69. In: Miller RD. Miller’s Anaesthesia. Philadelphia (PA): Churchill Livingstone/Elsevier; 2019.

5. Yip P, Middleton P, Cyna AM, Carlyle AV. Cochrane Review: non‐pharmacological interventions for assisting the induction of anaesthesia in children. Evid Based Child Health. 2011 Jan;6(1):71–134. https://doi.org/10.1002/ebch.669.

6. Liguori S, Stacchini M, Ciofi D, Olivini N, Bisogni S, Festini F. Effectiveness of an App for reducing preoperative anxiety in children: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA paediatrics. 2016 Aug 1;170(8): e160533. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2016.0533.

7. Kain ZN, Mayes LC, Cicchetti DV, Bagnall AL, Finley JD, Hofstadter MB. The Yale Preoperative Anxiety Scale: how does it compare with a “gold standard”? Anesth Analg. 1997 Oct;85(4):783–8. https://doi.org/10.1213/00000539-199710000-00012 PMID:9322455

8. Marteau TM, Bekker H. The development of a six-item short-form of the state scale of the Spielberger State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI). Br J Clin Psychol. 1992 Sep;31(3):301–6. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-8260.1992.tb00997.x PMID:1393159

9. Bajwa SA, Costi D, Cyna AM. A comparison of emergence delirium scales following general anesthesia in children. Paediatr Anaesth. 2010 Aug;20(8):704–11. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1460-9592.2010.03328.x PMID:20497353

10. Hicks CL, von Baeyer CL, Spafford PA, van Korlaar I, Goodenough B. The Faces Pain Scale-Revised: toward a common metric in pediatric pain measurement. Pain. 2001 Aug;93(2):173–83. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0304-3959(01)00314-1 PMID:11427329

11. Lee JH, Jung HK, Lee GG, Kim HY, Park SG, Woo SC. Effect of behavioral intervention using smartphone application for preoperative anxiety in paediatric patients. Korean journal of anaesthesiology. 2013 Dec 1;65(6):508-18.

12. LeRoy S, Elixson EM, O’Brien P, Tong E, Turpin S, Uzark K; American Heart Association Pediatric Nursing Subcommittee of the Council on Cardiovascular Nursing; Council on Cardiovascular Diseases of the Young. Recommendations for preparing children and adolescents for invasive cardiac procedures: a statement from the American Heart Association Pediatric Nursing Subcommittee of the Council on Cardiovascular Nursing in collaboration with the Council on Cardiovascular Diseases of the Young. Circulation. 2003 Nov;108(20):2550–64. https://doi.org/10.1161/01.CIR.0000100561.76609.64 PMID:14623793

13. Smith L, Callery P. Children’s accounts of their preoperative information needs. J Clin Nurs. 2005 Feb;14(2):230–8. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2702.2004.01029.x PMID:15669932

14. McCann ME, Kain ZN. The management of preoperative anxiety in children: an update. Anesth Analg. 2001 Jul;93(1):98–105. https://doi.org/10.1097/00000539-200107000-00022 PMID:11429348

15. Fernandes S, Arriaga P, Esteves F. Using an educational multimedia application to prepare children for outpatient surgeries. Health Commun. 2015;30(12):1190–200. https://doi.org/10.1080/10410236.2014.896446 PMID:25144403

16. Lakshman K, Mamatha HS, Rachana ND, Sumitha CS, Ranganath N, Gowda VB, et al. Effectiveness of Preoperative Multimedia Video-based Education on Anxiety and Haemodynamic Stability of Oncosurgery Patients Undergoing Spinal AnaesthesiaA Randomised Controlled Trial. J Clin Diagn Res. 2022;16(1):UC27–32.

17. Seiden SC, McMullan S, Sequera-Ramos L, De Oliveira GS Jr, Roth A, Rosenblatt A, et al. Tablet-based Interactive Distraction (TBID) vs oral midazolam to minimize perioperative anxiety in pediatric patients: a noninferiority randomized trial. Paediatr Anaesth. 2014 Dec;24(12):1217–23. https://doi.org/10.1111/pan.12475 PMID:25040433

18. Mustafa MS, Shafique MA, Zaidi SD, Qamber A, Rangwala BS, Ahmed A, et al. Preoperative anxiety management in pediatric patients: a systemic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials on the efficacy of distraction techniques. Front Pediatr. 2024 Feb;12:1353508. https://doi.org/10.3389/fped.2024.1353508 PMID:38440185

19. Cassady JF Jr, Wysocki TT, Miller KM, Cancel DD, Izenberg N. Use of a preanesthetic video for facilitation of parental education and anxiolysis before pediatric ambulatory surgery. Anesth Analg. 1999 Feb;88(2):246–50. https://doi.org/10.1213/00000539-199902000-00004 PMID:9972735

20. Ryu JH, Oh AY, Yoo HJ, Kim JH, Park JW, Han SH. The effect of an immersive virtual reality tour of the operating theater on emergence delirium in children undergoing general anesthesia: A randomized controlled trial. Paediatr Anaesth. 2019 Jan;29(1):98–105. https://doi.org/10.1111/pan.13535 PMID:30365231

21. Akin A, Bayram A, Esmaoglu A, Tosun Z, Aksu R, Altuntas R, et al. Dexmedetomidine vs midazolam for premedication of pediatric patients undergoing anesthesia. Paediatr Anaesth. 2012 Sep;22(9):871–6. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1460-9592.2012.03802.x PMID:22268591

22. Elebute OA, Ademuyiwa AO, Seyi-olajide JO, Bode CO. An audit of parental satisfaction of paediatric day case surgery at the Lagos University Teaching Hospital. J Clin Sci. 2014 Jul;11(2):44. https://doi.org/10.4103/1595-9587.146501.

ORCID

ORCID