Angélica Paola Fajardo1,2, Lina Marcela Valencia1,2, Silvia Margarita Clavijo1, Diego Aldemar Quesada1,2, María José Andrade López1,3*

Recibido: 15-05-2024

Aceptado: 24-12-2024

©2025 El(los) Autor(es) – Esta publicación es Órgano oficial de la Sociedad de Anestesiología de Chile

Revista Chilena de Anestesia Vol. 54 Núm. 5 pp. 725-728|https://doi.org/10.25237/revchilanestv54n5-31

PDF|ePub|RIS

Manejo anestésico con catéter epidural caudal guiado por ultrasonido para el cierre primario de exstrofia vesical en un neonato: Reporte de caso

Abstract

The exstrophy-epispadias complex is a spectrum of congenital malformations in which the main predictor for functional adverse outcomes and higher health costs is failed primary closure. We present the case of a 13-day old new-born who underwent primary closure of bladder exstrophy under general anaesthesia. We highlight some factors of the perioperative anaesthetic approach that may have influenced the successful primary closure. These factors include fluid management guided by hemodynamic goals and multimodal analgesic management involving an ultrasound-guided caudal epidural catheter.

Resumen

El complejo de extrofia-epispadias es un espectro de malformaciones congénitas en el cual el principal predictor de resultados funcionales adversos y mayores costos de salud es el fallo en el cierre primario. Presentamos el caso de un recién nacido de 13 días que se sometió al cierre primario de la extrofia vesical bajo anestesia general. Destacamos algunos factores del enfoque anestésico perioperatorio que pudieron haber influido en el éxito del cierre primario. Estos factores incluyen el manejo de líquidos guiado por objetivos hemodinámicos y el manejo analgésico multimodal que involucró un catéter epidural caudal guiado por ultrasonido.

-

Introduction

The exstrophy-epispadias complex is a spectrum of congenital malformations that involves multiple organ systems such as the genitourinary, gastrointestinal, and musculoskeletal systems. Classical bladder exstrophy is the most common presentation and is accompanied by a defect in the abdominal wall that exposes the bladder plate, pubic bone diastasis and epispadias. It occurs in one of 10,000 to 50,000 live births, being more common in male than females[1]. A failed primary closure is the main predictor for adverse functional and surgical outcomes, as well as increased costs of care. Given this, multiple techniques have been evaluated to decrease said risk, among the strategies are pelvic osteotomies and immobilization of the lower limbs. However, in neonates, it is desirable to achieve successful primary closure without the need for osteotomies due to the associated risks, such as nervous damage, bleeding, and transfusion requirements[2].

Postoperative pain management plays a significant role after bladder exstrophy closure. In neonates, epidural analgesia has demonstrated effectiveness in pain control, reducing opioid and muscle relaxants use, and managing the metabolic response to surgical stress. Additionally, it can facilitate early extubation and improve tolerance to lower limb immobilization. However, performing epidural analgesia in neonates can be challenging and carries a higher risk of complications. Factors such as anatomical considerations, technical difficulties, and the potential for adverse effects need to be considered[3]. We present the case of a neonate with bladder exstrophy who underwent a primary closure, in whom perioperative management factors such as the insertion of a caudal epidural catheter as part of multimodal analgesic strategy, could have influenced a successful outcome.

-

Case

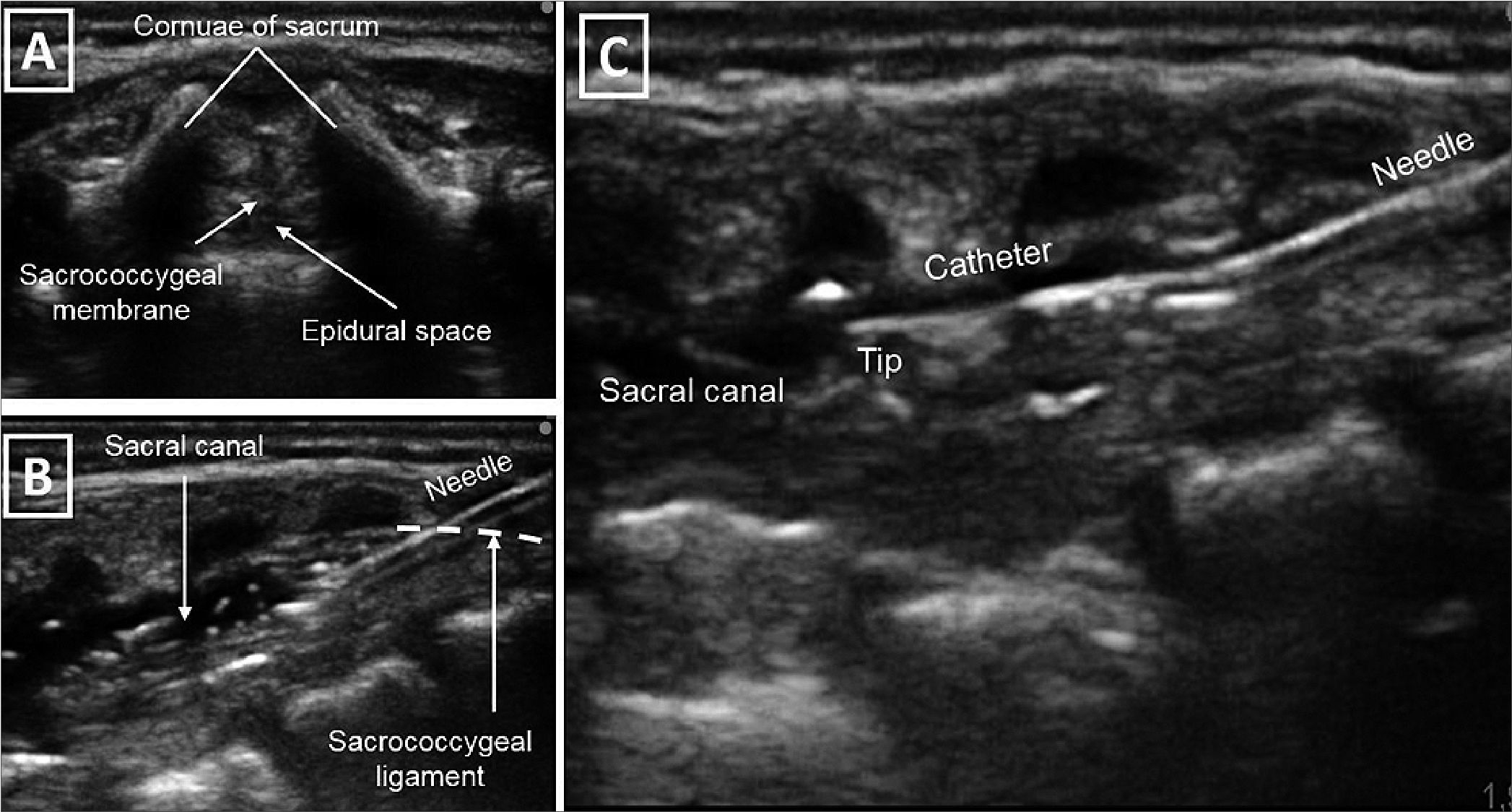

A term new-born weighing 2,800 grams was delivered vaginally at 38 weeks. He exhibited adequate adaptation but was diagnosed with multiple conditions including bladder exstrophy, pubic diastasis, corpus cavernosum malunion, and epispadias. Further extension studies were conducted, which included an echocardiogram revealing a persistent ductus arteriosus, satisfactory biventricular function, and no signs of pulmonary hypertension. An abdominal ultrasound confirmed the presence of left renal agenesis. Complete blood counts and renal function were found to be within normal limits. At 13 days of age, weighing 2.8 kg, the patient was admitted to the operating room for bladder exstrophy correction. During the procedure, the patient received basic monitoring, including inhaled sevoflurane at a concentration of 6 vol% and intravenous fentanyl at a dosage of 4 mcg/kg for induction. Orotracheal intubation was performed using a 3.0 uncuffed tube. Invasive monitoring was established through the placement of an ultrasound-guided right internal jugular central venous catheter and a left radial arterial line. With the patient positioned in left lateral decubitus, and following strict antiseptic technique, a high-frequency linear transducer was used to guide the procedure. A 20 g Touhy needle was inserted sacrococcygeally, and a peridural catheter was advanced up to t10-t11 level without any complications (Figure 1). Anaesthetic maintenance included a bolus of 1.5 cc/ kg of 0.1% bupivacaine through the catheter, and sevoflurane at 1 mac. A dose of Cisatracurium was used for neuromuscular relaxation, as was needed to aid the introduction of the bladder into the abdominal cavity and for approximation of the pubic rami. Throughout the 5-hour duration of the procedure, 10 cc of bleeding was obtained; urine output was not measured. Fluid resuscitation was guided by haemodynamic parameters such as heart rate, blood pressure and subjective variability of arterial line morphology. We administered 0.9% saline and 5% albumin, with which a neutral fluid balance was achieved. For transitional analgesia, a second bolus of 1 cc/kg of 0.1% bupivacaine was administered through the epidural catheter, along with 2 mcg/kg of fentanyl. At the end of the procedure, the patient exhibited spontaneous breathing with satisfactory ventilator mechanics, was normothermic, normoglycemic and with adequate acid-base equilibrium. Based on these favourable conditions, the decision was made to extubate the patient in the operating room. His lower limbs were immobilized, and he was transferred to the neonatal intensive care unit.

Postoperative analgesia was achieved with an infusion of 0.3 cc/kg/h 0.1% bupivacaine through the peridural catheter for 48 hours. No systemic opioids were necessary during the postoperative period. The patient exhibited a successful clinical course, characterized by hemodynamic stability, the absence of respiratory depression episodes, and no need for supplemental oxygen. Oral intake was initiated 24 hours after the surgery and was well-tolerated. He was discharged on the eighth day after surgery.

-

Discussion

The surgical management of bladder exstrophy aims to achieve multiple goals, including preserving renal function, attaining urinary continence, and achieving aesthetic reconstruction of the genitalia. Different approaches, such as complete primary closure or staged management, can be employed in neonates or older patients. While both techniques have shown successful outcomes in various studies, some suggest that primary closure in neonates offers superior results by eliminating the need for osteotomies, thereby reducing blood loss, risk of wound dehiscence, bladder prolapse, and postoperative pain[9],[10]. This approach is associated with improved outcomes in terms of cosmetic results, urinary continence, and overall quality of life[2]. Effective pain control, in addition to appropriate sedation, has been shown to decrease postoperative complications and closure failure[1].

Providing optimal pain management after extensive surgery is particularly challenging in neonatal and infant populations. Due to their immature central nervous system, they are more susceptible to the respiratory-depressant and hemodynamic effects of opioids and sedative drugs. Epidural analgesia provides a wide range of advantages for paediatric patients. It accelerates the recovery process, expedites the weaning from ventilators, decreases the duration of stay in paediatric intensive care units, reduces healthcare costs, shortens the period of catabolic states, and lowers the levels of stress hormone circulating[3].

Extensive research supports the use of epidural analgesia in abdominal and pelvic surgery, with guidelines recommending its incorporation as part of a multimodal approach following significant procedures in these areas. Case reports also highlight the successful application of continuous epidural analgesia in closing vesical exstrophy[3]. However, the use of epidural blocks is associated with hemodynamic changes due to its impact on systemic vascular resistance, primarily through sympathetic blockade[4]. Paediatric patients face additional challenges and a higher risk of complications when undergoing this technique, including neurological complications, bacterial colonization, mild motor impairment, local anaesthetic toxicity, and difficulties in catheter insertion, maintenance, and management, especially in very young patients[3].

Caudal block guided by anatomical landmarks shows a reported failure rate ranging from 3% to 11%, therefore, accurate placement of epidural needles and catheters is essential for both single-shot and continuous epidural anaesthesia[4]. This ensures selective blocking of the involved dermatomes during surgery, leading to lower doses of local anaesthetics[6]. Infants have unique sacral anatomy and fat distribution compared to adults, making ultrasonography a valuable tool for providing real-time and personalized information. The size and incomplete ossification of the vertebrae allow precise visualization and localization of the epidural space’s depth, resistance loss, important neuraxial structures, needle tip position, and spread of local anaesthetic[7],[8].

Figure 1. (A) Transversal cross section of the neural axis through the sacral hiatus; (B) Longitudinal cross section of the neuro axis. The needle inserted in plane through sacrococcygeal ligament to the sacral canal; (C) Ultrasound guided insertion of the epidural catheter with direct visualization of the tip. Source: Authors.

In our case, employing ultrasound guidance during the caudal catheter insertion, enabled us to precisely position the catheter tip at the intended intervertebral level. The accurate placement facilitated effective pain management without the need for opioids, promoted tolerance to lower limb immobilization, and allowed for the early initiation of oral intake. Additionally, the ultrasound-guided localization of the catheter tip at the desired intervertebral level potentially contributed to the patient requiring lower infusion rates of anaesthesia, thereby minimizing the occurrence of secondary hemodynamic changes.

When selecting the appropriate local anaesthetic for continuous epidural infusion in neonates, several factors need to be considered. Neonates are more susceptible to local anaesthetic toxicity due to their lower serum protein concentrations, which can result in higher serum levels of the anaesthetic. Bupivacaine is commonly used but carries the highest risk for potentially fatal cardiac arrhythmias caused by elevated blood levels[1]. Ropivacaine, on the other hand, causes less motor blockade and has prolonged systemic absorption when administered epidurally, which can be further extended with the addition of epinephrine[11]. Lidocaine is another option with a long history of safety and efficacy, and its serum levels can be easily monitored to detect potential toxicity. However, lidocaine has a shorter duration of action compared to bupivacaine and ropivacaine. Nevertheless, when administered through continuous infusion, this limitation becomes less significant. Regular measurement of lidocaine levels can help minimize the risk of systemic toxicity[1]. There have been reports of successful lidocaine epidural infusions in neonates for up to 30 days without signs of local anaesthetic toxicity at a dosage of 0.8 mg/kg/hr (19.2 mg/kg/day)[10]. Despite these options, the optimal and safe dosages of bupivacaine or ropivacaine for epidural infusions in neonates and young infants have not been established due to limited available information. In neonates, administration of lidocaine 1 mg/mL at a rate no higher than 0.8 mg/kg/hour is recommended[1].

In our case, the continuous infusion of 0.3 cc/kg/h 0.1% bupivacaine for 48 hours postoperatively, showed no signs of systemic toxicity or hemodynamic instability. This approach effectively eliminated the need for postoperative opioids and minimized the associated side effects. Based on the available evidence, we believe that if a caudal catheter is required for a duration exceeding 48 hours, the use of lidocaine may be a favourable option due to its advantages in terms of easy monitoring and lower risk of toxicity. This choice serves as a favourable alternative until a safe protocol for prolonged continuous infusion of bupivacaine or ropivacaine in neonates is established[1].

Similarly, caudally placed epidural catheters are prone to bacterial colonization within 48-72 hours after insertion. In our case, there were no signs of local or systemic catheter-associated infection within 48 hours, however, according to the literature, although the incidence of local and systemic infections is uncommon, tunnelling these catheters can effectively lower the risk of infection, particularly when they are intended to remain in position for more than 72 hours[10].

In conclusion, the perioperative anaesthesia management plays a critical role in the primary closure of bladder exstrophy, as it not only has an impact on immediate results but also in long-term outcomes. In our case, the use of ultrasonography for caudal catheter insertion, resulted in optimized intra- and postoperative outcomes, with added benefits in terms of neonatal safety. However, further randomized studies are necessary to establish a standardized anaesthetic protocol for this type of surgery.

Acknowledgments: Published with the written consent of the patient’s mother.

Competing conflicts: The authors declare to have no conflict of interests.

Funding: No external funding and no competing interests declared.

-

References

1. Inouye BM, Massanyi EZ, Di Carlo H, Shah BB, Gearhart JP. Modern management of bladder exstrophy repair. Curr Urol Rep. 2013 Aug;14(4):359–65. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11934-013-0332-y PMID:23686356

2. Mushtaq I, Garriboli M, Smeulders N, Cherian A, Desai D, Eaton S, et al. Primary bladder exstrophy closure in neonates: challenging the traditions. J Urol. 2014 Jan;191(1):193–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.juro.2013.07.020 PMID:23871929

3. Farid IS, Kendrick EJ, Adamczyk MJ, Lukas NR, Massanyi EZ. Perioperative Analgesic Management of Newborn Bladder Exstrophy Repair Using a Directly Placed Tunneled Epidural Catheter with 0.1% Ropivacaine. A A Case Rep. 2015 Oct;5(7):112–4. https://doi.org/10.1213/XAA.0000000000000191 PMID:26402021

4. Triffterer L, Marhofer P, Lechner G, Marksz TC, Kimberger O, Schmid W, et al. An observational study of the macro- and micro-haemodynamic implications of epidural anaesthesia in children. Anaesthesia. 2017 Apr;72(4):488–95. https://doi.org/10.1111/anae.13746 PMID:27891584

5. Willschke H, Bosenberg A, Marhofer P, Willschke J, Schwindt J, Weintraud M, et al. Epidural catheter placement in neonates: sonoanatomy and feasibility of ultrasonographic guidance in term and preterm neonates. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2007;32(1):34–40. https://doi.org/10.1097/00115550-200701000-00007 PMID:17196490

6. Sethi N, Chaturvedi R. Pediatric epidurals. J Anaesthesiol Clin Pharmacol. 2012 Jan;28(1):4–5. https://doi.org/10.4103/0970-9185.92409 PMID:22345936

7. Rapp HJ, Folger A, Grau T. Ultrasound-guided epidural catheter insertion in children. Anesth Analg. 2005 Aug;101(2):333–9. https://doi.org/10.1213/01.ANE.0000156579.11254.D1 PMID:16037140

8. Willschke H, Bosenberg A, Marhofer P, Willschke J, Schwindt J, Weintraud M, et al. Epidural catheter placement in neonates: sonoanatomy and feasibility of ultrasonographic guidance in term and preterm neonates. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2007;32(1):34–40. https://doi.org/10.1097/00115550-200701000-00007 PMID:17196490

9. Palacios-Palacios L, Salazar-Ramirez KJ. Anestesia y analgesia para corrección de extrofia vesical. Reporte de 3 casos. Rev Colomb Anestesiol. 2015;43(3):254–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rca.2015.03.002 .

10. Kost-Byerly S, Jackson EV, Yaster M, Kozlowski LJ, Mathews RI, Gearhart JP. Perioperative anesthetic and analgesic management of newborn bladder exstrophy repair. J Pediatr Urol. 2008 Aug;4(4):280–5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpurol.2008.01.207 PMID:18644530

11. Wiegele M, Marhofer P, Lönnqvist PA. Caudal epidural blocks in paediatric patients: a review and practical considerations. Br J Anaesth. 2019 Apr;122(4):509–17. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bja.2018.11.030 PMID:30857607

ORCID

ORCID