Gregory Contreras-Pérez1, Hipólito Labandeyra1*, Gustavo Cuadros-Mendoza1, Alex Carví-Mallo1

Recibido: 25-07-2025

Aceptado: 16-08-2025

©2025 El(los) Autor(es) – Esta publicación es Órgano oficial de la Sociedad de Anestesiología de Chile

Revista Chilena de Anestesia Vol. 54 Núm. 5 pp. 767-769|https://doi.org/10.25237/revchilanestv54n5-41

PDF|ePub|RIS

Analgesia multimodal libre de opiodes en xifoescoliosis severa

Abstract

Anesthetic management in extensive scoliosis surgeries presents specific challenges, especially concerning analgesia and postoperative recovery, particularly in adolescent or pediatric patients. This case describes a 16-year-old patient undergoing thoracolumbar arthrodesis (T3-L3) in which a multimodal anesthetic approach was used, achieving effective pain control without the use of morphine during the first 48 hours postoperatively.

Resumen

El manejo anestésico en cirugías extensas de escoliosis presenta desafíos específicos, especialmente en cuanto a la analgesia y la recuperación posoperatoria, sobre todo en pacientes adolescentes o pediátricos. Este caso describe a un paciente de 16 años sometido a una artrodesis toracolumbar (T3-L3) en la que se utilizó un enfoque anestésico multimodal, logrando un control eficaz del dolor sin el uso de morfina durante las primeras 48 horas posoperatorias.

-

Introduction

Severe scoliosis is a condition that requires complex surgical treatment, especially in adolescents, where spinal deformity can progress rapidly, affecting respiratory function and causing chronic pain[1]. Thoracolumbar arthrodesis surgeries, which involve multiple levels of the spine, are typically lengthy and demanding in terms of anesthetic and analgesic management, requiring a combination of techniques to ensure intraoperative hemodynamic stability and adequate postoperative pain control[1]. In the context of young patients, minimizing opioid use becomes a priority due to its significant side effects and potential for dependency[2]. Here, we present a case of a 16-year-old male adolescent diagnosed with severe scoliosis and grade I obesity, scheduled for extensive thoracolumbar arthrodesis from T3 to L3. A multimodal, opioid-free anesthesia approach was employed, monitoring postoperative morphine requirements within the first 48 hours post-surgery.

-

Report

A 16-year-old adolescent patient with a BMI of 32.2 kg/ m2 (115 kg and 189 cm) was scheduled for thoracolumbar arthrodesis (T3-L3) in October 2024 for kyphoscoliosis correction. His medical history included grade I obesity, with no known allergies, no chronic medication use, and no diagnosis of sleep apnea.

A pre-anesthetic evaluation was conducted, and the anesthetic technique was explained to the patient and his parents, obtaining informed consent.

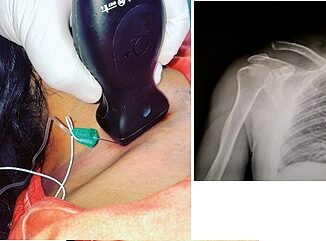

On the day of surgery, the patient was received in the pre-anesthesia area, where a pre-surgical checklist was completed. Two peripheral venous lines were established, with antibiotic prophylaxis administered, along with 2 mg IV midazolam, magnesium sulfate (50 mg/kg as a bolus over 30 minutes), and 1.5 g tranexamic acid. An arterial line was placed in the left radial artery, and he was then transferred to the operating room, where SpO2, ECG, invasive blood pressure, anesthetic depth, and nociception were monitored using the qCON and qNOX indices (Conox®, Quantium Medical, Barcelona, Spain). Doses were adjusted to the corrected body weight (99.4 kg), calculated with the Servin formula.

Before induction, dexketoprofen 50 mg, dexamethasone 8 mg, ondansetron 8 mg, and acetaminophen 1 g IV were administered. The patient was pre-oxygenated for 3 minutes, followed by fentanyl 3 mcg/kg, lidocaine 2 mg/kg, and ketamine 300 mcg/kg and methadone 0.15 mg/kg; then, dexmedetomidine (0.25 mcg/kg/h) and propofol infusions (Target Controlled Infusion) were initiated, using the Schnider model adjusted to a weight of 99.4 kg (adjusted total body weight), targeting a concentration of 5 mcg/ml at the effect site. Rocuronium 0.6 mg/kg was administered, achieving intubation without incident using an 8.5 tube and Glidescope® on the first attempt.

Mechanical ventilation was adjusted to lung-protective settings according to his weight. Anesthetic maintenance was performed with propofol infusions, dexmedetomidine 0.25 mcg/ kg/h, ketamine 300 mcg/kg/h, lidocaine 2 mg/kg/h, and magnesium sulfate 15 mg/kg/h. No neuromuscular relaxants were used to facilitate intraoperative neurophysiological monitoring.

The patient was positioned prone, ensuring attention to support points, with the bed slightly tilted in anti-Trendelenburg to reduce pressure on the face and eyes.

The patient remained hemodynamically stable throughout the surgery. Blood loss was approximately 800 ml, without clinical repercussions (permissible estimated loss at 2,000 ml). Fluid management was adjusted based on maintenance requirements, blood loss, urine output, and insensible losses. Periodic arterial blood gases reflected good metabolic, hemodynamic, and ventilatory status. The infusions of dexmedetomidine, ketamine, lidocaine, and magnesium sulfate were maintained until skin suturing was completed, with the propofol infusion gradually reduced. The patient was extubated without incident, with a verbal response at 5 minutes, appearing calm, cooperative, and pain-free. The total procedure duration was 6 hours and 45 minutes.

The patient was transferred to the Intensive Care Unit (ICU) for strict monitoring during the first 24 hours, with an analgesic regimen that included dexketoprofen (50 mg every 8 hours IV), metamizole (2 g every 12 hours IV), acetaminophen (1 g every 8 hours IV), and morphine rescue according to the Visual Analog Scale (VAS) > 3. He was discharged from the ICU and transferred to the general ward 24 hours after surgery.

-

Discussion

Severe kyphoscoliosis can lead to respiratory and cardiovascular deterioration. Previous studies have shown that postoperative pain following spinal surgery involves multiple pathways, including neuropathic, inflammatory, and nociceptive components. Postoperative pain is also directly related to the number of vertebral levels affected by the procedure[3].

When deformity reaches a certain severity, fixation or arthrodesis surgery is indicated to correct the existing deformity and prevent further progression. Traditional analgesic management for these patients has relied on intermittent opioid administration based on pain response or continuous intravenous morphine infusion via PCA. However, excessive and prolonged opioid use increases the likelihood of adverse reactions, including acute tolerance and opioid-induced hyperalgesia, which can delay recovery and hospital discharge[4].

Local anesthetic infusions at the surgical wound, epidural analgesia, or regional blocks such as paravertebral block, erector spinae plane block, the thoracolumbar interfascial plane block or intrathecal morphine have been reported to be effective in short-level arthrodesis (2-4 levels) at thoracic and lumbar regions. However, their effectiveness in open and extensive surgeries has not been validated. Epidural analgesia, in addition to the technical challenges in a young, obese patient with spinal deformity and the risk of catheter migration, is associated with risks of infection, hematoma, motor block, or unintentional dural puncture[5].

Notably, we did not observe hemodynamic instability (hypotension or bradycardia), as has been reported in some studies associated with the use of alpha-2 agonists[6]. This is likely due to the absence of an initial loading bolus and a maintenance dose of 0.25 mcg/kg/h[7]. This aspect is crucial in such interventions where hemodynamic stability is essential to ensure adequate spinal cord perfusion throughout the procedure, which can be compromised by blood loss.

We also did not observe psychomimetic effects associated with ketamine, despite using a maintenance dose of 300 mcg/ kg/h. Our patient had an average Ramsay scale score of 2 (calm, oriented, and cooperative) during the first 48 hours postoperatively.

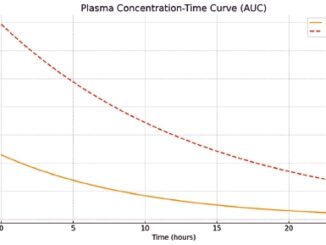

With a multimodal opioid-free approach as a strategy to reduce the risks associated with opioid use in a procedure of this magnitude, we were able to significantly reduce morphine consumption (0 mg) in the first 48 hours, marking the end of our clinical case. Independent infusions of propofol as a hypnotic agent and dexmedetomidine, lidocaine, and ketamine as adjuncts were used. The pharmacokinetic profiles of each drug were maintained by administering them separately. For dose calculation, the patient’s adjusted body weight was used, with processed EEG monitoring to avoid consequences of under or overdosing.

In this case, the patient did not require morphine rescue in the postoperative period, despite presenting risk factors for poor postoperative pain control, such as being young and obese[8]. Pain reduction and opioid requirements were achieved through the administration of drugs with recognized effects on the glutamatergic pathway, such as NMDA receptor antagonists. Ketamine and magnesium sulfate and even methadone, are essentials in reducing the incidence of central sensitization and hyperalgesia[9]. We include methadone in our approach because is the most suitable opioid to use as rescue analgesic for severe pain due to its anti NMDAr effect. Methadone decreases opioid induces hyperalgesia and attenuates the central sensitization phenomenon. In addition, the use of methadone with ketamine (both anti-NMDAr) shows a synergistic effect that enhances the opioid-sparing effect[10].

Recent publications have recommended the use of methadone (0.15 – 0.2 mg/kg bolus) at the start of anesthetic induction in complex spinal surgery[10]. Additionally, the anti-inflammatory and immunomodulatory effects of dexmedetomidine and lidocaine provide further benefits when used alongside NMDA receptor blockers[10].

To date, there are no standardized or universally accepted protocols that include specific guidelines on opioid-free anesthesia techniques for adolescent or pediatric patients undergoing extensive thoracolumbar arthrodesis surgery.

Conflict of Interests: The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Funding: No funding was received for this study.

-

References

1. Waelkens P, Alsabbagh E, Sauter A, Joshi GP, Beloeil H; PROSPECT Working group∗∗ of the European Society of Regional Anaesthesia and Pain therapy (ESRA). Pain management after complex spine surgery: A systematic review and procedure-specific postoperative pain management recommendations. Eur J Anaesthesiol. 2021 Sep;38(9):985–94. https://doi.org/10.1097/EJA.0000000000001448 PMID:34397527

2. Jones MR, Brovman EY, Novitch MB, Rao N, Urman RD. Potential opioid-related adverse events following spine surgery in elderly patients. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2019 Nov;186:105550. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clineuro.2019.105550 PMID:31610320

3. Rivkin A, Rivkin MA. Perioperative nonopioid agents for pain control in spinal surgery. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2014 Nov;71(21):1845–57. https://doi.org/10.2146/ajhp130688 PMID:25320134

4. Zhang Y, Cui F, Ma JH, Wang DX. Mini-dose esketamine-dexmedetomidine combination to supplement analgesia for patients after scoliosis correction surgery: a double-blind randomised trial. Br J Anaesth. 2023 Aug;131(2):385–96. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bja.2023.05.001 PMID:37302963

5. Koh WS, Leslie K. Postoperative analgesia for complex spinal surgery. Curr Opin Anaesthesiol. 2022 Oct;35(5):543–8. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACO.0000000000001168 PMID:35900754

6. You HJ, Lei J, Xiao Y, Ye G, Sun ZH, Yang L, et al. Pre-emptive analgesia and its supraspinal mechanisms: enhanced descending inhibition and decreased descending facilitation by dexmedetomidine. J Physiol. 2016 Apr;594(7):1875–90. https://doi.org/10.1113/JP271991 PMID:26732231

7. Feng M, Chen X, Liu T, Zhang C, Wan L, Yao W. Dexmedetomidine and sufentanil combination versus sufentanil alone for postoperative intravenous patient-controlled analgesia: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. BMC Anesthesiol. 2019 May;19(1):81. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12871-019-0756-0 PMID:31103031

8. Eipe N, Budiansky AS. Perioperative pain management in bariatric anesthesia. Saudi J Anaesth. 2022;16(3):339–46. https://doi.org/10.4103/sja.sja_236_22 PMID:35898528

9. Ji RR, Nackley A, Huh Y, Terrando N, Maixner W. Neuroinflammation and central sensitization in chronic and widespread pain. Anesthesiology. 2018 Aug;129(2):343–66. https://doi.org/10.1097/ALN.0000000000002130 PMID:29462012

10. Murphy GS, Avram MJ, Greenberg SB, Benson J, Bilimoria S, Maher CE, et al. Perioperative methadone and ketamine for postoperative pain control in spinal surgical patients: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Anesthesiology. 2021 May;134(5):697–708. https://doi.org/10.1097/ALN.0000000000003743 PMID:33730151

ORCID

ORCID