Amr Hosny Hamza Ali MD.1, Mohamed Farag Mohamed Morsi M.B.B.CH2*, Gamal Fouad Saleh Zaki M.D3, Ahmed Fayez Abd El Raof El Sayed MD4

Recibido: 02-02-2025

Aceptado: 05-05-2025

©2025 El(los) Autor(es) – Esta publicación es Órgano oficial de la Sociedad de Anestesiología de Chile

Revista Chilena de Anestesia Vol. 54 Núm. 6 pp. 891-895|https://doi.org/10.25237/revchilanestv54n6-16

PDF|ePub|RIS

Comparación entre bloqueo IPACK más canal aductor versus canal aductor en analgesia posoperatoria de artroscopias de rodilla

Abstract

Background: Arthroscopic knee surgeries are performed across various patient groups, emphasizing fasttrack recovery with early ambulation. Due to associated muscle weakness, traditional analgesic techniques like neuraxial and proximal nerve blocks are less favored. Pure sensory nerve blocks offer a promising alternative by relieving pain without impairing motor function. Methodology: Forty cases scheduled for arthroscopic knee surgery were randomized into two cohorts. Group A comprised twenty patients administered an ultrasound-guided adductor canal block (ACB) using 20 ml of 0.25% bupivacaine as the sole intervention. Group B, consisting of twenty patients received a dual approach: an ultrasound- guided ACB paired with infiltration of the interspace between the popliteal artery and capsule of the knee (IPACK) block using 20 ml of 0.25% bupivacaine for each block. Results: Although ACB alone delivered adequate pain relief, the combination of ACB and IPACK blocks yielded enhanced postoperative analgesia where postoperative VAS scores at 2, 4, 6, and 8 hours revealed statistically significant disparities between the groups (p < 0.001), with patients in Group B achieving increased ambulation distances during early recovery. Additionally, statistically significant disparities in opioid demand and total usage were noted between the two groups. Conclusion: Integrating ACB with IPACK blocks improves pain management outcomes following knee arthroscopy while avoiding compromise to motor capabilities in the knee joint. This dual approach further correlates with reduced reliance on opioid medications and superior postoperative mobility relative to isolated ACB administration.

Resumen

Antecedentes: Las cirugías de rodilla artroscópicas se realizan en diversos grupos de pacientes, haciendo hincapié en una recuperación rápida con una deambulación temprana. Debido a la debilidad muscular asociada, las técnicas analgésicas tradicionales como los bloqueos neuraxiales y proximales son menos favorecidas. Los bloqueos nerviosos puramente sensoriales ofrecen una alternativa prometedora al aliviar el dolor sin afectar la función motora. Metodología: Cuarenta casos programados para cirugía artroscópica de rodilla fueron aleatorizados en dos cohortes. El Grupo A comprendía veinte pacientes a quienes se les administró un bloqueo del canal aductor (ACB) guiado por ultrasonido utilizando 20 ml de bupivacaína al 0,25% como única intervención. El Grupo B, compuesto por veinte pacientes, recibió un enfoque dual: un bloqueo del canal aductor (ACB) guiado por ultrasonido junto con la infiltración del espacio entre la arteria poplítea y la cápsula de la rodilla (bloqueo IPACK) utilizando 20 ml de bupivacaína al 0,25% para cada bloqueo. Resultados: Aunque el ACB solo proporcionó un alivio adecuado del dolor, la combinación de los bloques ACB e IPACK produjo una analgesia posoperatoria mejorada, donde las puntuaciones de VAS posoperatorias a las 2, 4, 6 y 8 h revelaron disparidades estadísticamente significativas entre los grupos (p < 0,001), con pacientes en el Grupo B logrando mayores distancias de ambulación durante la recuperación temprana. Además, se observaron disparidades estadísticamente significativas en la demanda y el uso total de opioides entre los dos grupos. Conclusión: Integrar ACB con bloqueos IPACK mejora los resultados en el manejo del dolor tras una artroscopia de rodilla, evitando comprometer las capacidades motoras en la articulación de la rodilla. Este enfoque dual se correlaciona además con una menor dependencia de los medicamentos opioides y una movilidad postoperatoria superior en comparación con la administración aislada de ACB.

-

Introduction

Knee arthroscopy is a widely performed orthopedic procedure globally. Although it is less invasive than traditional knee surgery, postoperative pain can still be severe, often necessitating substantial opioidbased analgesia for adequate pain management[1].

Numerous patients face opioid-related adverse effects, such as sedation, respiratory depression, nausea, vomiting, and constipation, especially when opioids are consumed in high quantities for pain relief[2]. Peripheral nerve blocks effectively alleviate pain and markedly decrease the need for opioids, thus reducing the likelihood of complications linked to opioid use[3].

Rehabilitation and early mobilization are essential for successful recovery after knee arthroscopy[4]. Intense pain can impede movement and prolong rehabilitation, potentially compromising recovery results[5].

Research indicates that a significant proportion of patients report moderate to severe pain during the initial 24 hours after ambulatory surgeries, especially following knee arthroscopy. Such pain can substantially reduce patient mobility and diminish satisfaction with the surgical outcome[6]. Optimal postoperative pain management correlates with increased patient satisfaction, enhanced short-term recovery, and shorter hospitalization periods[7].

The adductor canal block (ACB), a peripheral nerve block technique, delivers effective analgesia for arthroscopic knee surgery patients, particularly in regions around and within the knee joint. A key benefit of ACB is its ability to maintain quadriceps muscle function, causing little to no motor weakness. However, ACB does not sufficiently alleviate posterior knee pain, which is frequently moderate to severe[8].

The interspace between the popliteal artery and posterior knee capsule (IPACK) block aims to anesthetize sensory branches of the sciatic nerve in this area without affecting motor function. While this method is employed in multiple clinical settings, evidence supporting its efficacy is scarce. As the IPACK block alone is inadequate for comprehensive pain management, it is often paired with ACB in a multimodal analgesic strategy[9].

-

Objective of the study

This study aims to assess and contrast the efficacy of postoperative pain relief when combining the IPACK block with ACB versus using ACB alone in patients undergoing arthroscopic knee procedures.

-

Patients and Methods

This prospective, randomized, controlled, double-blind clinical experiment was undertaken after receiving approval from the institutional ethics committee. Informed consent was acquired from all participants after a comprehensive description of the research protocol. Participant privacy and data confidentiality were ensured throughout all phases of the study.

The research included patients aged 21 to 40 years with ASA physical status I or II, irrespective of sex, scheduled for arthroscopic knee surgery under spinal anesthesia (SA). The exclusion criteria included patients who refused participation, those with ASA level III or above, contraindications to spinal anesthetic, a history of drug allergies to the research drugs, local infections at the injection site, or neuromuscular problems like multiple sclerosis.

Forty patients receiving arthroscopic knee surgery were randomly allocated into two groups, including twenty patients each. A computer-generated randomization method was used, where patients with even numbers were allocated to Group A (receiving an ACB alone), while those with odd numbers were assigned to Group B (receiving both an ACB and an IPACK block).

All patients underwent the same preoperative preparation and anesthetic protocol. A thorough history and general examination were conducted for each patient, along with routine preoperative laboratory investigations, including a complete blood count, bleeding time, INR, partial thromboplastin time, and blood chemistry (hepatic and renal function tests). Age, weight, and sex were recorded. Additionally, all patients adhered to fasting guidelines, abstaining from clear fluids for 2 hours and solid meals for 8 hours before surgery.

Intravenous access was provided in the operating room, and patients were linked to monitors for the continuous assessment of baseline mean arterial pressure (MAP), heart rate (HR), electrocardiography (ECG), and oxygen saturation (SpO2). A 500 cc Ringer’s solution was supplied as a co-load with anesthesia under stringent aseptic conditions with 10% Betadine. All patients had SA in a seated posture using the midline technique. The skin was first infiltrated with 3 ml of 2% lidocaine for local anesthetic, after which a 25G spinal needle was inserted into the subarachnoid area. Once free cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) flow was confirmed, 3 ml of heavy bupivacaine was administered, after which the patient was positioned supine.

After 5 minutes, the effectiveness of SA was assessed using the Bromage scale for motor block evaluation and the cold sensation test for sensory block assessment. SA was considered sufficient if the sensory block level was above L1.

Patients in Group A underwent an ultrasound-guided ACB with an injection of 20 ml of 0.25% bupivacaine before surgery. The procedure was performed using high-frequency ultrasound guidance (SonoSite™, Inc., Bothell, WA, USA) after SA. Patients lay in a supine position with their arms comfortably resting on the chest and the affected leg externally rotated. The adductor canal, located beneath the sartorius muscle, was identified, and a 22-gauge, 90-mm spinal needle was inserted from an anterolateral to posteromedial direction at the junction of the middle and distal thirds of the thigh, known as the mid-adductor canal. Once correctly positioned, 20 ml of 0.25% bupivacaine was injected following the technique described by Elliott et al., 2015.

In Group B, patients received an ultrasound-guided ACB with 20 ml of 0.25% bupivacaine, followed by an IPACK block, both administered before surgery. The ACB was performed as described for Group A, followed by the IPACK block based on the method outlined by Elliott et al., 2015. For the IPACK block, patients were positioned supine with the knee bent at a 90° angle. A low-frequency ultrasound probe was placed at the popliteal crease, just above the patella. A spinal needle was inserted medially at the knee and advanced in an anteromedial to posterolateral direction between the popliteal artery and the femur. The needle tip was positioned 1-2 cm beyond the lateral edge of the artery, and 20 ml of 0.25% bupivacaine was slowly injected while withdrawing the needle, ensuring negative aspiration at each stage.

Vital signs, including blood pressure, pulse rate, and oxygen saturation, were continuously monitored at five-minute intervals to maintain patient stability. Oxygen supplementation via nasal prongs was provided when necessary. If patients experienced breakthrough pain after surgery, they were given 30 mg of intravenous pethidine as rescue analgesia. Randomization was carried out using a computer-generated coding system, and all nerve blocks were performed by an independent anesthesiologist with expertise in regional anesthesia.

Sample size

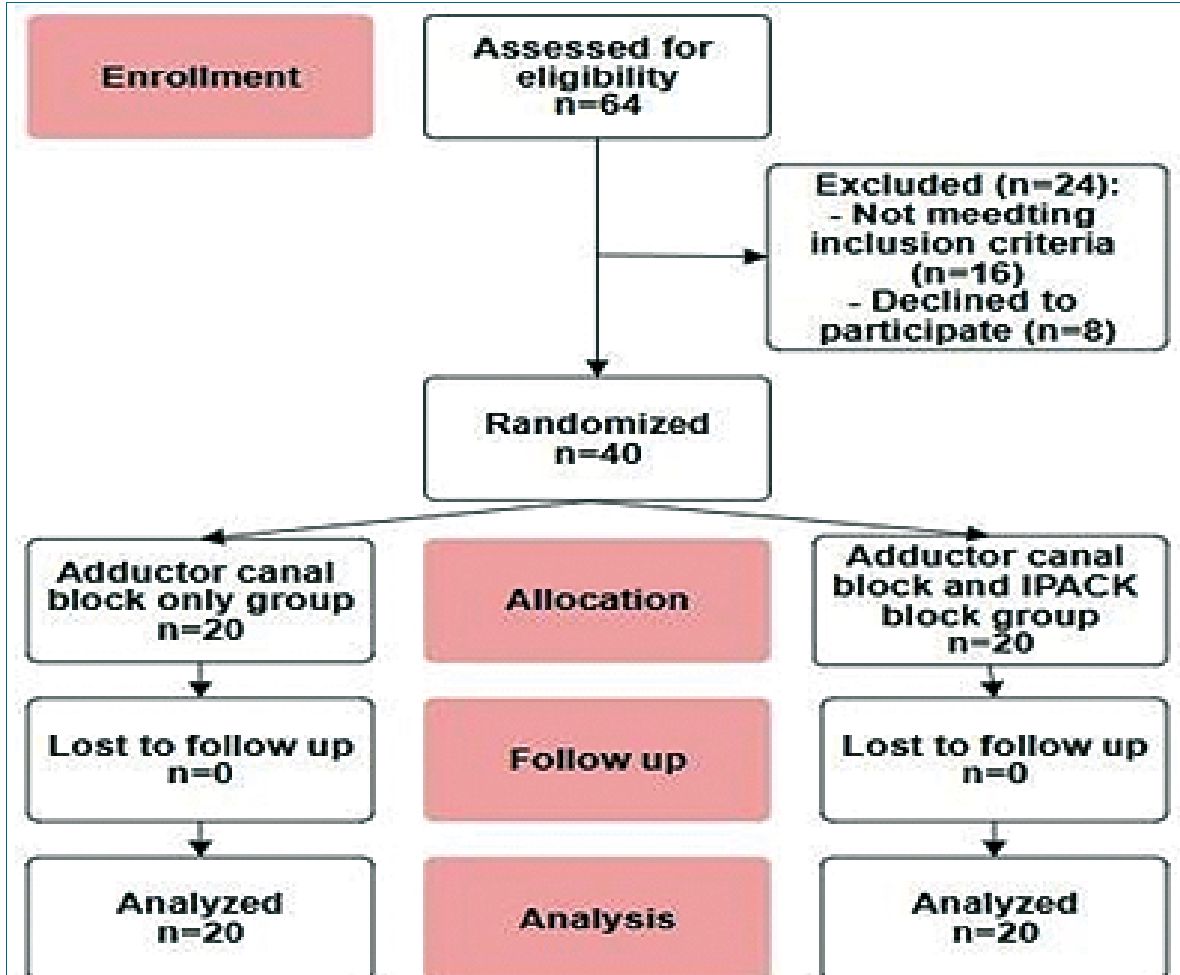

A sample size was estimated by using the PASS 11 software, which was based on previous research conducted by Sankineani et al. (2018). The a error for this determination was 5%. Following the completion of the inclusion criteria and the provision of permission, a total of forty patients who were scheduled to have arthroscopic knee surgery were randomly split into two groups of twenty each. Through the use of a computer-generated numbering system, randomization was carried out. Patients with even numbers were assigned to Group A, which received just ACB, while patients with odd numbers were assigned to Group B, which received both ACB and IPACK block (Figure 1).

Statistical methods

SPSS (Statistical Package for Social Sciences), version 23.0 (available from SPSS Inc. in Chicago, Illinois, United States of America), was used for the purpose of doing data analysis. According to the Kolmogorov-Smirnov and Shapiro-Wilk tests, the mean ± standard deviation (SD) and ranges were used to summarize the parametric variables. These tests were used to determine whether the variables were normal. The median and the interquartile range (IQR) were used to represent the nonparametric data, but the frequencies and percentages were used to describe the qualitative variables instead. The criteria for statistical significance were established as follows: p < 0.05 represented a significant finding, while p < 0.001 indicated a very significant finding.

Figure 1. Flowchart of the study.

-

Results

No significant differences were observed between Group A and Group B in demographic characteristics such as age, sex, ASA classification, BMI, or surgical duration (p > 0.05).

Similarly, baseline hemodynamic measures-heart rate, SpO2, and mean arterial blood pressure- showed no notable intergroup differences (p > 0.05).

Pain scores escalated over time in both groups (p < 0.001), with a steeper rise in Group A than Group B. Postoperative VAS scores at 2, 4, 6, and 8 hours revealed statistically significant disparities between the groups (p < 0.05).

Table (4) shows that the time to first analgesia (hours) was significantly earlier in Group A (3.90 ± 0.71 hours) compared to Group B (5.40 ± 1.50 hours), indicating that patients in Group B experienced longer pain relief before requiring additional analgesia.

There was a statistically significant higher mean pethidine consumption (mg) in Group A (45.0 ± 8.50 mg) compared to Group B (30.0 ± 0.00 mg), with a p-value of 0.019, indicating that patients in Group B required less opioid analgesia postoperatively.

Group B exhibited a significant increased number of postoperative steps walked (8.50 ± 1.16 vs. 7.00 ± 1.48 in Group A; p = 0.001), suggesting enhanced early mobility and functional recovery in Group B.

-

Discussion

In this study, the analgesic effects of an ACB alone were compared with those of ACB combined with an IPACK block in patients undergoing knee surgery. The analysis showed no statistically significant differences between the two groups (Groups A and B) in demographic variables such as age, sex, ASA classification, BMI, and surgery duration, with p-values exceeding 0.05. Similarly, baseline hemodynamic parameters, including heart rate, SpO2, and MAP, did not differ significantly between the groups (p > 0.05).

Pain assessment using the Visual Analogue Scale (VAS) at intervals of 1, 2, 4, 6, and 8 hours postoperatively revealed better pain control in the ACB + IPACK group compared to the ACB-alone group. While the 1-hour pain score difference was not significant (p = 0.303), significant improvements were observed at 2, 4, 6, and 8 hours (p = 0.016, < 0.001, < 0.001, and < 0.001, respectively). The time to first analgesia was shorter in Group A (3.90 ± 0.71 hours) than in Group B (5.40 ± 1.50 hours), with a p-value of 0.002. Pethidine was administered if the VAS score exceeded 4, and its consumption was significantly higher in Group A (45.0 ± 8.50 mg) compared to Group B (30.0 ± 0.00 mg), with a p-value of 0.019, indicating reduced opioid use in Group B.

Postoperative mobility was also better in Group B, with patients walking an average of 8.50 ± 1.16 steps compared to 7.00 ± 1.48 steps in Group A (p = 0.001), suggesting enhanced early mobilization and functional recovery in the ACB + IPACK group.

These findings are consistent with previous studies. Sanki- neani et al., reported that patients receiving a combined ACB + IPACK block experienced superior pain relief on the VAS, improved ROM, and greater walking distance compared to those receiving ACB alone. They also noted that posterior knee pain was the most frequent complaint among ACB-only patients within the first 24 hours postoperatively[10].

Li et al., found that ACB + IPACK patients had lower pain scores, reduced morphine consumption, and prolonged analgesia compared to those receiving only ACB. However, they observed no significant difference in mobility between the groups[11].

In a separate study, Tayfun et al., reported that ACB + IPACK patients experienced earlier discharge and mobilization, lower pain levels, and reduced opioid use compared to the ACB-only group[12].

Scimia et al., studied the efficacy of IPACK combined with continuous ACB for postoperative pain relief and early rehabilitation within 72 hours following TKR. Their findings indicated that compared to FNB, this approach provided similar pain control and opioid consumption while preserving quadriceps strength and enhancing mobility[13].

Thobhani et al., examined 106 adult patients across three groups: FNB alone, FNB + IPACK, and ACB + IPACK. Their results demonstrated that the ACB + IPACK group had superior PT performance and earlier hospital discharge compared to those receiving either FNB alone or FNB + IPACK[14].

Kampitak et al., investigated the motor-sparing effects of IPACK versus TNB. Their study randomized 105 patients to receive either an IPACK block or TNB alongside SA. Motor function was assessed via the TUG test, quadriceps strength, ROM, LOS, and patient satisfaction. Results showed that tibial nerve motor function was better preserved in the IPACK group than in the TNB group[15].

A 2021 study by Singtana found that IPACK recipients had significantly lower opioid consumption at 12 hours post-op compared to ACB-only patients. However, no significant differences were observed in pain scores (NPRS), total analgesic use, patient satisfaction, or complication rates[16].

Elliot et al., highlighted that combining ACB + IPACK enhances PT outcomes, reduces pain intensity, decreases opioid use, and shortens hospitalization. However, their study showed that the ACB + IPACK group did not exhibit lower VAS scores. Compared to the FNB + IPACK group, they had slightly higher opioid consumption. Nevertheless, within the first 48 hours post-op, ACB + IPACK patients demonstrated longer walking distances and higher discharge rates[8].

Furthermore, Patterson et al., found that patients receiving ACB + IPACK reported lower pain scores on the VAS within the first 48 hours post-op compared to those receiving ACB alone[17].

A 2023 study conducted by Tamam et al. indicated that ACB administration for knee arthroscopy, particularly at the proximal AC injection site, reduced opioid consumption and improved post-op pain control. Their findings also suggested that ACB did not cause motor blockade per the Bromage scale. Additionally, the proximal AC injection site resulted in lower PONV rates and greater patient satisfaction[18].

Zeng et al., demonstrated that combining IPACK with ACB provided superior post-op pain relief after AKS compared to ACB alone. Their study showed extended analgesic duration, reduced opioid use, and improved early mobility while preserving quadriceps strength, facilitating faster rehab, and lowering post-op complications[19].

This study was limited by small sample size, and the single center. Further research with larger, multicenter trials is warranted to confirm these findings.

-

Conclusion

In summary, utilizing both ACB and IPACK techniques improves postoperative pain management without compromising knee joint mobility. This combination also leads to lower opioid requirements and greater postoperative ambulation in contrast to ACB alone.

-

References

1. Jaeger P, Nielsen ZJ, Henningsen MH, Hilsted KL, Mathiesen O, Dahl JB. Adductor canal block versus femoral nerve block and quadriceps strength: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, crossover study in healthy volunteers. Anesthesiology. 2013 Feb;118(2):409–15. https://doi.org/10.1097/ALN.0b013e318279fa0b PMID:23241723

2. Jenstrup MT, Jæger P, Lund J, Fomsgaard JS, Bache S, Mathiesen O, et al. Effects of adductor-canal-blockade on pain and ambulation after total knee arthroplasty: a randomized study. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2012 Mar;56(3):357–64. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1399-6576.2011.02621.x PMID:22221014

3. Manickam B, Perlas A, Duggan E, Brull R, Chan VW, Ramlogan R. Feasibility and efficacy of ultrasound-guided block of the saphenous nerve in the adductor canal. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2009;34(6):578–80. https://doi.org/10.1097/AAP.0b013e3181bfbf84 PMID:19916251

4. Lundblad M, Forssblad M, Eksborg S, Lönnqvist PA. Ultrasound-guided infrapatellar nerve block for anterior cruciate ligament repair: a prospective, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial. European Journal of Anaesthesiology| EJA. 2011 Jul 1;28(7):511-8. https://doi.org/10.1097/EJA.0b013e32834515ba.

5. Hanson NA, Derby RE, Auyong DB, Salinas FV, Delucca C, Nagy R, et al. Ultrasound-guided adductor canal block for arthroscopic medial meniscectomy: a randomized, double-blind trial. Can J Anaesth. 2013 Sep;60(9):874–80. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12630-013-9992-9 PMID:23820968

6. Pavlin DJ, Chen C, Penaloza DA, Buckley FP. A survey of pain and other symptoms that affect the recovery process after discharge from an ambulatory surgery unit. J Clin Anesth. 2004 May;16(3):200–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinane.2003.08.004 PMID:15217660

7. Akkaya T, Ersan O, Ozkan D, Sahiner Y, Akin M, Gümüş H, et al. Saphenous nerve block is an effective regional technique for post-menisectomy pain. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2008 Sep;16(9):855–8. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00167-008-0572-4 PMID:18574578

8. Elliott CE, Myers TJ, Soberon JR. The adductor canal block combined with iPACK improves physical therapy performance and reduces hospital length of stay. In40th annual regional anesthesiology and acute pain medicine meeting (ASRA) 2015 May 14.

9. Reddy DA, Jangale A, Reddy RC, Sagi M, Gaikwad A, Reddy A. To compare effect of combined block of adductor canal block (ACB) with IPACK (Interspace between the Popliteal Artery and the Capsule of the posterior Knee) and adductor canal block (ACB) alone on Total knee replacement in immediate postoperative rehabilitation. Int J Orthop Sci. 2017;3(2):141–5. https://doi.org/10.22271/ortho.2017.v3.i2c.21.

10. Sankineani SR, Reddy AR, Eachempati KK, Jangale A, Gurava Reddy AV. Comparison of adductor canal block and IPACK block (interspace between the popliteal artery and the capsule of the posterior knee) with adductor canal block alone after total knee arthroplasty: a prospective control trial on pain and knee function in immediate postoperative period. Eur J Orthop Surg Traumatol. 2018 Oct;28(7):1391–5. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00590-018-2218-7 PMID:29721648

11. Li D, Alqwbani M, Wang Q, Liao R, Yang J, Kang P. Efficacy of adductor canal block combined with additional analgesic methods for postoperative analgesia in total knee arthroplasty: a prospective, double-blind, randomized controlled study. J Arthroplasty. 2020 Dec;35(12):3554–62. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arth.2020.06.060 PMID:32680754

12. Et T, Korkusuz M, Basaran B, Yarımoğlu R, Toprak H, Bilge A, et al. Comparison of iPACK and periarticular block with adductor block alone after total knee arthroplasty: a randomized clinical trial. J Anesth. 2022 Apr;36(2):276–86. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00540-022-03047-6 PMID:35157136

13. Scimia P, Giordano C, Ricci EB, Budassi P, Petrucci E, Fusco P. The ultrasound-guided iPACK block with continuous adductor canal block for total knee arthroplasty. Anaesth Cases. 2017 Jan;5(1):74–8. https://doi.org/10.21466/ac.TUIBWCA.2017.

14. Thobhani S, Scalercio L, Elliott CE, Nossaman BD, Thomas LC, Yuratich D, et al. Novel regional techniques for total knee arthroplasty promote reduced hospital length of stay: an analysis of 106 patients. Ochsner J. 2017;17(3):233–8. PMID:29026354

15. Kampitak W, Tanavalee A, Ngarmukos S, Tantavisut S. Motor-sparing effect of iPACK (interspace between the popliteal artery and capsule of the posterior knee) block versus tibial nerve block after total knee arthroplasty: a randomized controlled trial. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2020 Apr;45(4):267–76. https://doi.org/10.1136/rapm-2019-100895 PMID:32024676

16. Singtana K. Comparison of adductor canal block and ipack block with adductor canal block alone for postoperative pain control in patients undergoing total knee arthroplasty. Thai Journal of Anesthesiology. 2021;47(1):1–9.

17. Patterson ME, Vitter J, Bland K, Nossaman BD, Thomas LC, Chimento GF. The effect of the IPACK block on pain after primary TKA: a double-blinded, prospective, randomized trial. J Arthroplasty. 2020 Jun;35(6 6S):S173–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arth.2020.01.014 PMID:32005622

18. Tamam A, Güven Köse S, Köse HC, Akkaya ÖT. Comparison of the Effectiveness of Ultrasound-Guided Proximal, Mid, or Distal Adductor Canal Block after Knee Arthroscopy. Turk J Anaesthesiol Reanim. 2023 Apr;51(2):135–42. https://doi.org/10.5152/TJAR.2023.22225 PMID:37140579

19. Zeng J, Yang X, Lei H, Zhong X, Lu X, Liu X, et al. Enhanced postoperative Pain Management and mobility following arthroscopic knee surgery: a comparative study of Adductor Canal Block with and without IPACK Block. Med Sci Monit. 2024 Jul;30:e943735–1. https://doi.org/10.12659/MSM.943735 PMID:39068511

ORCID

ORCID