Katerina Bastidas Viritch1, Fabricio Andres Lasso Andrade2 , David A. Rincón Valenzuela3, Yolid Andrea Zuleta Martínez4

Recibido: 25-05-2024

Aceptado: —

©2025 El(los) Autor(es) – Esta publicación es Órgano oficial de la Sociedad de Anestesiología de Chile

Revista Chilena de Anestesia Vol. 54 Núm. 4 pp. 362-368|https://doi.org/10.25237/revchilanestv54n4-04

PDF|ePub|RIS

Abstract

Background and Objective: Fear and anxiety are common emotions among patients prior to surgery. This study aimed to evaluate the concordance between patients’ perceptions of the risks associated with anesthetic complications and the actual estimated risks in non-cardiac scheduled surgery. Methods: A cross-sectional study was conducted on 171 patients attending a pre-anesthetic consultation at a university hospital. A survey was administered to assess risk perception, and data from medical records were collected to calculate the actual risks using validated scales (NSQIP, revised cardiac risk, Apfel, ARISCAT). Concordance was analyzed using the weighted Kappa coefficient, and the association of perioperative anxiety (APAIS >11) with sociodemographic variables and specific fears. Results: Patients tended to overestimate the risks, with minimal concordance between perceptions and actual risks. Fear of intraoperative awareness (OR 9.08, CI 95% 2.49 – 58.48) and postoperative pain (OR 4.03, CI 95% 1.75 – 9.71) were significant predictors of clinically relevant perioperative anxiety. No associations were found between sociodemographic characteristics and anxiety. Conclusion: There is a significant discrepancy between patients’ risk perceptions and the actual estimated risks. Specifically addressing fears related to intraoperative awareness and postoperative pain could help reduce preoperative anxiety. Improving education and communication about the true risks is crucial.

Resumen

Antecedentes y Objetivo: El miedo y la ansiedad son emociones comunes en pacientes antes de la cirugía. Este estudio tuvo como objetivo evaluar la concordancia entre la percepción de los pacientes sobre los riesgos asociados a complicaciones anestésicas y los riesgos reales estimados en cirugía programada no cardíaca. Métodos: Se realizó un estudio transversal en 171 pacientes que acudieron a la consulta preanestésica en un hospital universitario. Se aplicó una encuesta para evaluar la percepción de riesgos y se recopilaron datos de las historias clínicas para calcular los riesgos reales utilizando escalas validadas (NSQIP, revisada de riesgo cardíaco, Apfel, ARISCAT). Se analizó la concordancia mediante el coeficiente Kappa ponderado y la asociación de la ansiedad perioperatoria (APAIS > 11) con variables sociodemográficas y temores específicos. Resultados: Los pacientes tendieron a sobreestimar los riesgos, con una concordancia mínima entre percepciones y riesgos reales. El miedo al despertar intra- operatorio (OR 9,08, IC 95% 2,49 – 58,.48) y al dolor posoperatorio (OR 4,03, IC 95% 1,75 – 9,71) fueron predictores significativos de ansiedad perioperatoria clínicamente relevante. No se encontraron asociaciones entre características sociodemográficas y ansiedad. Conclusión: Existe una discrepancia significativa entre la percepción de riesgos de los pacientes y los riesgos reales estimados. Abordar específicamente los temores relacionados con el despertar intraoperatorio y el dolor posoperatorio podría ayudar a reducir la ansiedad preoperatoria. Mejorar la educación y comunicación sobre los verdaderos riesgos es crucial.

-

Introduction

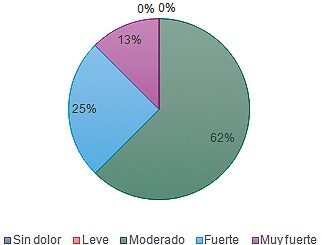

Fear and anxiety are common emotions experienced by patients prior to undergoing a surgical procedure[1],[2]. It has been reported that the majority of patients in the preoperative phase experience some level of anxiety or fear, with an incidence of up to 61%-99%[3],[4]. Moreover, it has been identified that in scheduled surgery, predominant fears are associated with anesthesia, up to 62%, rather than the surgery itself[5]. Additional studies have found that the main fear, regardless of the surgery’s severity, is death, and this fear decreases with age[6]. In contrast, other studies have shown that there is greater fear of postoperative pain and experiencing intraoperative awakening than of death itself[7],[8].

The presence of these negative feelings in the preoperative period has been linked to multiple adverse outcomes, such as delayed recovery, high doses of anesthetics use, nausea, vomiting, cardiovascular alterations, increased risk of infection, and difficulty in pain management[9]-[11]. Additionally, pain itself has been associated with other complications, such as myocardial injury, hypoventilation, decreased functional capacity, pneumonia, urinary retention, oliguria, inadequate healing, and coagulopathy[12],[13].

To address this issue, some European countries, such as Switzerland and the United Kingdom, have implemented anesthesia rooms, spaces separate from the operating room designed for the administration of induction and other anesthetic procedures, to create a calm environment and reduce patient anxiety[14]. Another intervention studied has been the presurgery medical visit, but it has been evidenced that more than 45% of visited patients did not manage to reduce their anxiety levels[3].

This is why it is crucial to understand patients’ perceptions of the risks associated with anesthesia and surgery, and how this perception compares to the actual estimated risks. The overall objective of this research is to evaluate the concordance between the perception patients have of the risks associated with different anesthetic complications and the actual estimated risks in the context of non-cardiac scheduled surgery. Our study aims to identify which anesthetic complications generate fear in pre-surgical non-cardiovascular patients and their association with perioperative anxiety, in addition to exploring the associations between sociodemographic characteristics and perioperative anxiety, and determining which complications generate the most fear and are determinants of perioperative anxiety.

-

Methods

An analytical cross-sectional observational study was conducted.Before data collection began, the protocol was approved by the ethics committee of the Hospital Universitario Nacional (HUN) and the Universidad Nacional de Colombia on February 2, 2002, under the reference CEI-HUN-AC- TA-2022-01. The subjects of this study were patients assessed in the pre-anesthetic clinic and scheduled for non-cardiac elective surgery at the Hospital Universitario Nacional. The sample size was estimated based on an anticipated Kappa value of 0.5 for the first measurement and 0.7 for the second, aiming to achieve a statistical power of 90% and an alpha significance level of 0.05[15]. A convenience sampling included all patients from the pre-anesthetic clinic list at the HUN, aiming for a total sample size of 171 patients.

The study population comprised patients over 18 years old, attending the pre-anesthetic clinic, and scheduled for outpatient non-cardiac surgery at the HUN. Patients with independent neurocognitive deterioration of any etiology, delirium, or unwillingness to participate in the study were excluded.

Initially, a paper survey was administered before the preanesthetic evaluation at the HUN. Patients were informed about the study objectives, survey details, had their questions answered, and signed informed consent. Each patient was assigned a code from 01 to 171 to maintain anonymity, with their identity known only to the principal investigator. This procedure not only protected patient confidentiality but also minimized selection bias, as the allocation of anonymous codes prevented any potential influence related to patient identity on the study’s results. Additionally, to address information bias, a comprehensive electronic form was implemented, which could only be submitted once fully completed. This approach ensured that there were no missing data, further enhancing the reliability of the study findings. To mitigate the risk of confounding, the study employed multivariate statistical analysis, allowing for the control of potential confounders and providing a more accurate estimation of the effects of the studied variables. The individual responsible for the statistical analysis did not have access to the information until the sample collection was completed. Subsequently, an evaluation of electronic medical records was conducted to collect data from the pre-anesthetic and intraoperative assessments, in order to complete various risk scales (NSQIP, revised cardiac risk, Apfel scale, ARISCAT score)[16]-[19] and to gather sociodemographic characteristics. For calculating the risk of postoperative nausea and vomiting,

scenarios were assumed where patients were administered opioids.

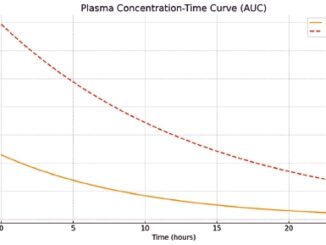

A descriptive analysis of the collected variables was conducted. Discrete variables were described using relative frequencies, while quantitative variables were summarized using mean and standard deviation. Data related to mortality risk, postoperative nausea and vomiting (NVPO), surgical site infection, and thrombotic events such as deep vein thrombosis (DVT) and pulmonary embolism (PE) were categorized into quintiles. The risk of acute myocardial infarction (AMI) was classified into quartiles, and the risk of pulmonary complications was divided into tertiles. This stratification facilitated alignment with a Likert scale ranging from 1 to 10, where a score of 0 indicated ‘impossibility’ and 10 ‘certainty,’ to gauge the likelihood of the mentioned complications occurring. Risks were categorized as low, low-intermediate, intermediate, high-intermediate, and high for variables analyzed in quintiles; low, low-intermediate, high-intermediate, and high for those analyzed in quartiles; and low, intermediate, and high for those evaluated in tertiles.

A concordance analysis was performed using the weighted Kappa test[20], suitable for variables of real and patient-estimated risk categorized on an ordinal scale, to assess the concordance between patient perception and the risks calculated according to the NSQIP, ARISCAT, and Apfel scales. Furthermore, the correlation and association of APAIS scores > 11, considered clinically significant for perioperative anxiety[21], were analyzed. For continuous variables, normality was verified using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test[22]. Categorical variables were assessed using the Chi-square test with Yates’ correction or Fisher’s exact test, applied in cells with frequencies less than five[23],[24]. Fear levels, rated from 1 to 4, were dichotomized into ‘some degree of fear’ or ‘no fear’ categories for their association with APAIS scores > 11. A statistical significance threshold of p < 0.05 was established for all analyses. Additionally, a multivariate analysis was conducted using binary logistic regression, with APAIS > 11 as the dependent variable, presenting only those variables that demonstrated statistical significance in terms of odds ratios (OR) with a 95% confidence interval. McFadden’s RA2 was also used as a model fit estimator[25].

Table 1. Clinical and sociodemographic characteristics

| Variable | n = 171 (%) |

| Age | |

| Mean ± SD | 50.6 ± 17.41 |

| Median (IQR) | 48 (37.5 – 65) |

| Sex (Female) | 125 (73.1) |

| ASA | |

| I | 50 (29.24) |

| II | 82 (47.95) |

| III | 39 (22.81) |

| Provenance | |

| Bogotá | 94 (54.97) |

| Andina | 28 (16.37) |

| Pacífico | 7 (4.09) |

| Caribe | 3 (1.75) |

| Amazonia | 2 (1.17) |

| Otra | 37 (21.65) |

| Education Level | |

| Primary School | 32 (18.71) |

| Secondary School | 43 (25.15) |

| Technical | 36 (21.05) |

| Undergraduate | 32 (18.71) |

| Postgraduate | 25 (14.62) |

| Non-schooled | 3 (1.75) |

| Socioeconomic Status | |

| 1-3 | 148 (86.55) |

| 4-6 | 23 ( 13.45) |

| Previous Surgery (Yes) | 128 (85) |

| Depression and Anxiety (No) | 160 (93.57) |

| Lee Index (Class 1) | 142 (83.04) |

| APAIS Score > 11 | 137 (80.12) |

| ARISCAT (Low Risk) | 160 (93.57) |

| APFEL | |

| 0 | 2 (1.17) |

| 1 | 7 (4.09) |

| 2 | 47 (27.49 |

| 3 | 88 (51.46) |

| 4 | 27 (15.79) |

SD: standard deviation; IQR: interquartile range; ASA: American Society of Anesthesiologists; ARISCAT: Assess Respiratory Risk in Surgical Patients in Catalonia; APFEL: Assessment of Postoperative Nausea and Vomiting; APAIS: Amsterdam Preoperative Anxiety and Information Scale.

-

Results

A total of 171 participants were enrolled and completed the study. The clinical and sociodemographic characteristics of the participants are detailed in Table 1. The average age was 50.6 years, with a standard deviation of 17.41 years. The majority of participants (73.1%) were female. Regarding the American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) classification, most were categorized as ASA II (47.95%). Educational levels varied, with the majority having secondary education or higher. Most patients had a history of previous surgery and perioperative anxiety determined by an APAIS score > 11. Table 2 presents the comparison between perceived and actual perioperative risks for complications such as mortality, surgical site infection, and thrombosis.

However, the concordance between patients’ perceptions and actual risks, measured through the Weighted Kappa Coefficient, suggested minimal agreement, as highlighted in Table 2. Additional analyses evaluated the association of sociode-

mographic variables with high levels of perioperative anxiety (APAIS > 11), as shown in Table 3. Factors such as educational level and previous surgical experiences were analyzed for their impact on anxiety levels. These analyses helped identify potential areas for intervention to reduce anxiety.

The logistic regression analysis, detailed in Table 4, identified significant predictors of perioperative anxiety (APAIS > 11). Specifically, the fear of intraoperative awakening showed a strong association with higher APAIS scores, with an odds ratio of 9.08, indicating a substantial impact on patient anxiety. Similarly, fear of postoperative pain was significantly associated with an odds ratio of 4.03.

The place of origin was distributed as follows: most pa-

tients were from Bogotá (54.97%), followed by the Andean region (16.37%), and the rest were distributed among the other regions. The predominant socioeconomic status was in the 1-3 strata (86.55%), while only 13.45% belonged to the 4-6 strata. Regarding educational level, 25.15% of patients had secondary education, followed by 21.05% with technical training. A total of 85% of participants had undergone previous surgeries. Regarding the scales used, 93.57% of patients were classified as low- risk according to the ARISCAT scale, and 51.46% had a score of 3 on the APFEL scale, indicating a high risk of postoperative nausea.

Table 2. Comparison of actual and estimated perioperative risks

| Perioperative complication | Perceived Risk n = 171 (%) | Actual Risk n = 171 (%) | Weighted Kappa Coefficient | p -Value |

| Mortality | ||||

| Low -0-1.48% (0-2 points) | 97 (56.73) | 168 (98.24) | ||

| Low – Intermediate 1.49-2.96% (3-4 points) | 23 (13.45) | 1 (0.59) | ||

| Intermediate 2.97-4.44% (5-6 points) | 24 (14.04) | 0 (0) | -0.0042 | 0.909 |

| High – Intermediate 4.45-5.92% (7-8 points) | 6(3.51) | 0 (0) | ||

| High -5.92-7.4% (9-10 points) | 21 (12.28) | 2 (1.17) | ||

| Lee Score (MI/Cardiac Arrest within 30 Days) | ||||

| Low -3.90% (0-2 points) | 99 (57.89) | 142 (83.04) | ||

| Low – Intermediate 6.00% (3-5 points) | 43 (25.15) | 27 (15.79) | 0.000965 | 0.844 |

| High – Intermediate 10.10% (6-8 points) | 13 (7.60) | 1 (0.58) | ||

| High – 15% (9-10 points) | 16 (9.36) | 1 (0.58) | ||

| Surgical Site Infection | ||||

| Low – 1.72% (0-2 points) | 77 (45.03) | 134 (78.36) | ||

| Low – Intermediate 1.73-3.44 (3-4 points) | 33 (19.3) | 25 (14.62) | ||

| Intermediate 3.45-5.16% (5-6 points) | 18 (10.53) | 10 (5.83) | -0.00455 | 0.133 |

| High – Intermediate 5.17-6.88% (7-8 points) | 24 (14.04) | 0 (0) | ||

| High – 6.89-8.60% (9-10 points) | 19 (11.11) | 2 (1.17) | ||

| Thrombosis (PE/DVT) | ||||

| Low – 0.9% (0-2 points) | 100 (58.48) | 151 (88.3) | ||

| Low – Intermediate 1.0-1.8% (3-4 points) | 19 (11.11) | 18 (10.53) | ||

| Intermediate- 1.9-2.7% (5-6 points) | 28 (16.37) | 1 (0.58) | 0.00182 | 0.325 |

| High – Intermediate 2.8-3.6% (7-8 points) | 12 (7.02) | 0 (0) | ||

| High – 3.7-4.5 (9-10 points) | 12 (7.02) | 1 (0.58) | ||

| Pulmonary Complications | ||||

| Low – 1.60% (0-3 points) | 120 (70.18) | 160 (93.57) | ||

| Intermediate -13.30% (4-7 points) | 35 (20.47) | 11 (6.43) | -0.00201 | 0.531 |

| High – 42.10% (8-10 points) | 16 (9.36) | 0 (0) | ||

| Postoperative Nausea and Vomiting | ||||

| Low -10% (0-2 points) | 73 (42.69) | 2 (1.17) | ||

| Low – Intermediate 21% (3-4 points) | 33 (19.3) | 7 (4.09) | ||

| Intermediate 39% (5-6 points) | 32 (18.71) | 47 (27.49) | 0.0132 | 0.000345 |

| High – Intermediate 61% (7-8 points) | 16 (9.36) | 88 (51.46) | ||

| High – 79% (9-10 points) | 17 (9.94) | 27 (15.79) |

Weighted Kappa Coefficient: A statistical measure that assesses inter-rater agreement for ordinal data, accounting for the severity of disagreements and chance agreement.

-

Discussion

This study aimed to assess the agreement between patients’ perceptions of the risks associated with various anesthetic com

plications and the actual estimated risks in non-cardiac elective surgery. It also sought to identify anesthetic complications that cause fear in pre-surgical non-cardiovascular patients, explore the links between sociodemographic characteristics and perioperative anxiety, and determine which complications are most fear-inducing and influential in driving perioperative anxiety.

The key findings of this study reveal a significant discrepancy between patients’ perceptions of perioperative risks and the actual estimated risks. Consistent with previous studies, patients tended to overestimate the risks, with minimal agreement between perceptions and actual calculations, as measured through the Weighted Kappa Coefficient[26]. This contrasts with some earlier reports of greater concordance, but supports the broader evidence that patients have a limited understanding of the true risks associated with anesthetic and surgical procedures. This gap in risk perception

could have significant implications for preoperative anxiety and informed decision-making[27].

Regarding the factors associated with perioperative anxiety, the logistic regression analysis identified fear of intraoperative awareness and postoperative pain as significant predictors of APAIS scores > 11, which are considered clinically relevant. This suggests that these specific fears have a substantial impact on patients’ preoperative anxiety and should be addressed in the perioperative setting due to the adverse postoperative outcomes associated with perioperative anxiety[28].

However, the study has some limitations that must be considered. Firstly, being a cross-sectional design, it does not allow for causality to be established between the analyzed variables, only associations. Additionally, the sample was selected for convenience, which could introduce selection bias and limit the generalizability of the results. Moreover, the assessment of actual risks was based on scales and risk calculators, which, al

though validated tools, may have some degree of imprecision. Another limitation is that the study was conducted in a single hospital center, which could affect the representativeness of the population. Furthermore, psychological factors beyond anxiety, which could influence risk perception and perioperative anxiety, were not evaluated.

Table 3. Association and Correlation of Sociodemographic Variables with Clinically Relevant Perioperative Anxiety (APAIS > 11)

| Variable | Association p – Value | Correlation |

| Age | – | -0.17547* |

| Sex | 0.5586+ | – |

| ASA | 0.5708+ | – |

| Provenance | 0.6451 + | – |

| Education Level | 0.8612+ | – |

| Socioeconomic Status | 0.7156+ | – |

| Previous Surgery | 0.6747+ | – |

| Depression and Anxiety | 0.6952+ | – |

| Some Degree of Fear (Score 2 to 4) | ||

| – Pain | < 0.01 + | |

| – Intraoperative Awareness | < 0.01 + | |

| – Postoperative Nausea and Vomiting | 0.1073+ | |

| – Death | < 0.01 + | |

| – Not Regain Consciousness | 0.2343+ | |

| – Transient/Permanent Cognitive Impairments | 0.7418+ | |

| – Pulmonary Complication | 0.2063+ | |

| No Fear (Score 1) | ||

| – Acute Myocardial Infarction | 0.0465+ | |

| – Surgical Site Infection | 0.02836+ | – |

| – Thrombotic Events (PE/DVT) | 0.0465+ |

Significance indicators: + p < 0.05; + p < 0.1. ASA: American Society of Anesthesiologists classification; PE/DVT – Pulmonary Embolism/Deep Vein Thrombosis. *: Biserial Correlation; +: Chi-squared test with Yates continuity correction; + : Fisher’s Exact Test.

Table 4. Predictors of an APAIS score > 11: logistic regression

| OR (CI 95%) | p-value | R2 McFadden | |

| Pain | 4.03 (1.75 – 9.71) | 0.00135 | 0.248 |

| Intraoperative Awareness | 9.08 (2.49 – 58.48) | 0.00389 | |

| OR: Odds ratios; CI: 95% confidence intervals. A higher odds ratio indicates a stronger association with APAIS scores above 11; McFadden’s R2 is provided to indicate the model fit. The variance inflation factor (VIF) values for the variables included in the model are; Pain = 1.77, Intraoperative Awareness = 1.30. VIF values below 5 suggest acceptable multicollinearity. | |||

Despite these limitations, the findings of this study have significant clinical implications. The discrepancy found between patients’ risk perceptions and the actual estimated risks underscores the need to improve education and communication between healthcare professionals and patients about the true risks associated with anesthetic and surgical procedures. This could help dispel unfounded fears and reduce preoperative anxiety. Additionally, identifying fear of intraoperative awareness and postoperative pain as key predictors of clinically significant perioperative anxiety highlights the importance of addressing these specific fears in preoperative care. Targeted

interventions to provide accurate information about the actual risks of these complications, as well as strategies for their prevention and management, could help reduce patient anxiety before surgery[29].

This study was conducted in a single hospital center, yet the population included patients from various geographical regions and socioeconomic levels, potentially increasing the representativeness of the findings. Nevertheless, it is important to replicate the study in other contexts and populations to assess the consistency of the results. Additionally, future studies could delve deeper into the analysis of other sociodemographic and psychological factors that may influence risk perception and perioperative anxiety, such as prior surgical experience, the presence of mental disorders, among others. Furthermore, it would be relevant to evaluate the impact of specific interventions, such as preoperative education, on reducing patient anxiety.

In conclusion, this study demonstrates a significant discrepancy between patients’ perceived risks and the actual estimated risks, as well as the importance of fear of intraoperative awareness and postoperative pain as predictors of perioperative anxiety. These findings underscore the need to improve communication and education about the real risks associated with anesthetic and surgical procedures, and to specifically address these fears in preoperative care. Replicating this study in other contexts and analyzing other relevant factors could contribute to a better understanding and management of preoperative anxiety.

Conflict of interest: Authors state no conflict of interest.

Funding: The research is self-funded from the authors.

-

References

1. Vileikyte L. Stress and wound healing. Clin Dermatol. 2007;25(1):49–55. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clindermatol.2006.09.005 PMID:17276201

2. Kefelegn R, Tolera A, Ali T, Assebe T. Preoperative anxiety and associated factors among adult surgical patients in public hospitals, eastern Ethiopia. SAGE Open Med. 15 de noviembre de 2023;11:20503121231211648. https://doi.org/10.1177/20503121231211648.

3. Masjedi M, Ghorbani M, Managheb I, Fattahi ZS, Dehghanpisheh L. Evaluation of anxiety and fear about anesthesia in adults undergoing surgery under general anesthesia. Acta Anaesth Belg. 1 de agosto de 2017;

4. Mulugeta H, Ayana M, Sintayehu M, Dessie G, Zewdu T. Preoperative anxiety and associated factors among adult surgical patients in Debre Markos and Felege Hiwot referral hospitals, Northwest Ethiopia. BMC Anesthesiol. 30 de octubre de 2018;18(1):155. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12871-018-0619-0

5. Ramsay M a. E. A survey of pre–operative fear*. Anaesthesia. octubre de 1972;27(4):396-402. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2044.1972.tb08244.x

6. Kindler CH, Harms C, Amsler F, Ihde-Scholl T, Scheidegger D. The visual analog scale allows effective measurement of preoperative anxiety and detection of patients’ anesthetic concerns. Anesth Analg. marzo de 2000;90(3):706-12. https://doi.org/10.1097/00000539-200003000-00036

7. Macario A, Weinger M, Carney S, Kim A. Which clinical anesthesia outcomes are important to avoid? The perspective of patients. Anesth Analg. septiembre de 1999;89(3):652-8. https://doi.org/10.1213/00000539-199909000-00022

8. Matthey PW, Finegan BA, Finucane BT. The public’s fears about and perceptions of regional anesthesia. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2004;29(2):96–101. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rapm.2003.10.017 PMID:15029543

9. Rosenberger PH, Jokl P, Ickovics J. Psychosocial factors and surgical outcomes: an evidence-based literature review. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. julio de 2006;14(7):397-405. https://doi.org/10.5435/00124635-200607000-00002

10. Kiecolt-Glaser JK, Page GG, Marucha PT, MacCallum RC, Glaser R. Psychological influences on surgical recovery. Perspectives from psychoneuroimmunology. Am Psychol. noviembre de 1998;53(11):1209-18. https://doi.org/10.1037//0003-066X.53.11.1209

11. Maranets I, Kain ZN. Preoperative anxiety and intraoperative anesthetic requirements. Anesth Analg. diciembre de 1999;89(6):1346-51. https://doi.org/10.1213/00000539-199912000-00003

12. Joshi GP, Ogunnaike BO. Consequences of inadequate postoperative pain relief and chronic persistent postoperative pain. Anesthesiol Clin North Am. marzo de 2005;23(1):21-36. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atc.2004.11.013.

13. Kehlet H, Holte K. Effect of postoperative analgesia on surgical outcome. British Journal of Anaesthesia. 1 de julio de 2001;87(1):62-72. https://doi.org/10.1093/bja/87.1.62.

14. Torkki PM, Marjamaa RA, Torkki MI, Kallio PE, Kirvelä OA. Use of anesthesia induction rooms can increase the number of urgent orthopedic cases completed within 7 hours. Anesthesiology. agosto de 2005;103(2):401-5. https://doi.org/10.1097/00000542-200508000-00024.

15. Determining Sample Sizes Needed to Detect a Difference between Two Proportions. En: Statistical Methods for Rates and Proportions [Internet]. 2003 [citado 25 de mayo de 2024]. p. 64-85. (Wiley Series in Probability and Statistics). Disponible en: https://doi.org/10.1002/0471445428.ch4.

16. Khuri SF, Daley J, Henderson W, Barbour G, Lowry P, Irvin G, et al. The National Veterans Administration Surgical Risk Study: risk adjustment for the comparative assessment of the quality of surgical care. J Am Coll Surg. mayo de 1995;180(5):519-31.

17. Lee TH, Marcantonio ER, Mangione CM, Thomas EJ, Polanczyk CA, Cook EF, et al. Derivation and prospective validation of a simple index for prediction of cardiac risk of major noncardiac surgery. Circulation. 7 de septiembre de 1999;100(10):1043-9. https://doi.org/10.1161/01.CIR.100.10.1043.

18. Canet J, Gallart L, Gomar C, Paluzie G, Vallès J, Castillo J, et al. Prediction of postoperative pulmonary complications in a population-based surgical cohort. Anesthesiology. diciembre de 2010;113(6):1338-50. https://doi.org/10.1097/ALN.0b013e3181fc6e0a.

19. Apfel CC, Läärä E, Koivuranta M, Greim CA, Roewer N. A simplified risk score for predicting postoperative nausea and vomiting: conclusions from cross-validations between two centers. Anesthesiology. septiembre de 1999;91(3):693-700. https://doi.org/10.1097/00000542-199909000-00022.

20. Fleiss JL, Cohen J. The Equivalence of Weighted Kappa and the Intraclass Correlation Coefficient as Measures of Reliability. Educ Psychol Meas. 1973;33(3):613–9. https://doi.org/10.1177/001316447303300309.

21. Moerman N, van Dam FS, Muller MJ, Oosting H. The Amsterdam Preoperative Anxiety and Information Scale (APAIS). Anesth Analg. marzo de 1996;82(3):445-51. https://doi.org/10.1213/00000539-199603000-00002

22. Massey Jr. FJ. The Kolmogorov-Smirnov Test for Goodness of Fit. Journal of the American Statistical Association. 1 de marzo de 1951;46(253):68-78. https://doi.org/10.1080/01621459.1951.10500769.

23. Fisher RA. On the Interpretation of χ2 from Contingency Tables, and the Calculation of P. En 2010. Disponible en: https://api.semanticscholar.org/CorpusID:15378540

24. Yates F. Contingency Tables Involving Small Numbers and the χ2 Test. J R Stat Soc Series B Stat Methodol. 1934;1(2):217–35. https://doi.org/10.2307/2983604.

25. McFadden D. Conditional logit analysis of qualitative choice behavior. Frontiers in econometrics. 1974;

26. Caumo W, Schmidt AP, Schneider CN, Bergmann J, Iwamoto CW, Bandeira D, et al. Risk factors for preoperative anxiety in adults. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. marzo de 2001;45(3):298-307. https://doi.org/10.1034/j.1399-6576.2001.045003298.x.

27. Mavridou P, Dimitriou V, Manataki A, Arnaoutoglou E, Papadopoulos G. Patient’s anxiety and fear of anesthesia: effect of gender, age, education, and previous experience of anesthesia. A survey of 400 patients. J Anesth. 1 de febrero de 2013;27(1):104-8. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00540-012-1460-0

28. Pritchard MJ. Identifying and assessing anxiety in pre-operative patients. Nurs Stand. 26 de septiembre de 2009;23(51):35-40. https://doi.org/10.7748/ns.23.51.35.s46

29. Kruzik N. Benefits of preoperative education for adult elective surgery patients. AORN J. septiembre de 2009;90(3):381-7 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aorn.2009.06.022.

ORCID

ORCID