Martha Patricia Lázaro Ovalle MD.1, Fabricio Andrés Lasso Andrade MD.1,2*, Pedro José Herrera Gómez MSc.1

Recibido: 29-09-2024

Aceptado: 23-12-2024

©2025 El(los) Autor(es) – Esta publicación es Órgano oficial de la Sociedad de Anestesiología de Chile

Revista Chilena de Anestesia Vol. 54 Núm. 4 pp. 421-425|https://doi.org/10.25237/revchilanestv54n4-12

PDF|ePub|RIS

Dolor postoperatorio agudo en cesárea y ligadura tubular: Una cohorte prospectiva

Abstract

Background: Postoperative pain is a common complication in patients undergoing cesarean section and tubal ligation, affecting recovery and satisfaction. This study evaluates the intensity of postoperative pain at 2, 24, and 48 hours in patients who underwent cesarean section, cesarean with tubal ligation, or tubal ligation alone, under spinal anesthesia. Methods: A prospective cohort observational study was conducted in 73 patients at the Instituto Materno Infantil of Bogotá. Patients with pre-existing chronic pain or critical conditions were excluded. Postoperative pain was measured using the numeric pain scale at 2, 24, and 48 hours. Fisher’s exact test was used for categorical comparisons and the Wilcoxon test with continuity correction for ordinal variables, applying Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons. Results: At 2 hours postoperatively, 89% of patients reported no pain, while 20.5% experienced severe pain at 24 hours, and 16.5% reported severe pain at 48 hours. No statistically significant differences were found between pain levels at 24 and 48 hours (p = 0.4094). Furthermore, no significant differences were observed in pain levels between the three types of procedures (cesarean section, cesarean with tubal ligation, and tubal ligation alone) at any of the measured time points (2 hours, p = 0.1037; 24 hours, p = 0.9685; 48 hours, p = 0.88). Conclusion: Postoperative pain increased between 2 and 24 hours, remaining elevated at 48 hours, with no significant differences between procedures. The need to improve postoperative pain management regardless of the type of surgery is highlighted.

Resumen

Antecedentes: El dolor posoperatorio agudo es una complicación común en pacientes sometidas a cesárea y ligadura tubárica, afectando la recuperación y la satisfacción. Este estudio evalúa la intensidad del dolor posoperatorio a las 2, 24 y 48 h en pacientes sometidas a cesárea, cesárea con ligadura tubárica, o ligadura tubárica sola, bajo anestesia subaracnoidea. Métodos: Se realizó un estudio observacional de cohorte prospectivo en 73 pacientes del Instituto Materno Infantil de Bogotá. Se excluyeron pacientes con dolor crónico preexistente o en estado crítico. El dolor posoperatorio se midió utilizando la escala numérica del dolor a las 2, 24 y 48 h. Para el análisis estadístico se empleó la prueba exacta de Fisher para comparaciones categóricas y la prueba de Wilcoxon con corrección de continuidad para variables ordinales, aplicando corrección de Bonferroni en comparaciones múltiples. Resultados: A las 2 h posoperatorias, el 89% de las pacientes no reportaron dolor, mientras que el 20,5% experimentó dolor severo a las 24 h, y el 16,5% reportó dolor severo a las 48 h. No se encontraron diferencias estadísticamente significativas entre los niveles de dolor a las 24 y 48 h (p = 0,4094). Además, no se observaron diferencias significativas en los niveles de dolor entre los tres tipos de procedimientos (cesárea, cesárea con ligadura tubárica, y ligadura tubárica sola) en ninguno de los momentos medidos (2 h, p = 0,1037; 24 h, p = 0,9685; 48 h, p = 0,88). Conclusión: El dolor posoperatorio aumenta entre las 2 y 24 h, manteniéndose elevado a las 48 h, sin diferencias significativas entre los procedimientos. Se destaca la necesidad de mejorar el manejo del dolor posoperatorio independientemente del tipo de cirugía.

-

Introduction

Postoperative pain is a major concern in the management of patients undergoing surgical procedures such as cesarean section and tubal ligation. According to reports from the World Health Organization (WHO), annually, 18.5 million cesarean sections are performed globally, of which approximately 6 million are considered unnecessary. It is believed that the cesarean section rate should not exceed 15% anywhere in the world[1].

In Colombia, in 2016, the proportion of births by cesarean section was 46.4% at the national level, with a slight decrease to 44.6% by 2020. In public health institutions (IPS), the proportion of cesarean sections increased from 26.2% in 1998 to 42.9% in 2014, while in private institutions it increased from 45.0% to 57.7% in 2013. The prevalence ratio of cesarean sections in private institutions compared to public ones was 1.57 (95% CI: 1.56-1.57)[2]. In Brazil, between 2014 and 2017, it was observed that the cesarean section rate was 80.0% in patients without prenatal care, 45.2% in those with inadequate prenatal care, 43.0% for those with adequate care, and 50.5% in the group with “adequate plus” care[3], showing similar proportions of cesarean sections reported in Latin America. Cesarean section rates above 30% in Latin America are concerning due to their association with higher perioperative morbidity and mortality[4].

High-efficacy contraceptive measures, such as tubal ligation, can significantly contribute to improving post-cesarean morbidity and mortality rates. This procedure is increasingly common among women, especially in the immediate postpartum period, particularly in those with higher parity[5]. Tubal ligation not only offers a permanent contraceptive method but also reduces the risk of complications in future pregnancies[6].

Although these surgical procedures are considered to have lower pain scores, postoperative pain for tubal ligations has shown average scores of 4.74 and for cesarean section 6.14 on the numerical pain scale[7]. This pain is associated with decreased patient satisfaction, delayed ambulation, the development of chronic pain, and increased morbidity and mortality[8].

The primary objective of this study is to evaluate the intensity of acute postoperative pain in patients undergoing cesarean section, with or without tubal ligation, under spinal anesthesia. Secondary objectives include characterizing sociodemographic, clinical, and surgical variables, as well as pain management. Additionally, the study aims to establish relationships between pain intensity (mild, moderate, or severe) and the type of procedure performed, evaluating these parameters at three key postoperative moments, up to 48 hours after the procedure.

-

Methods

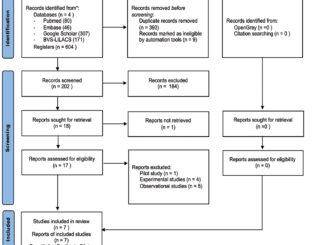

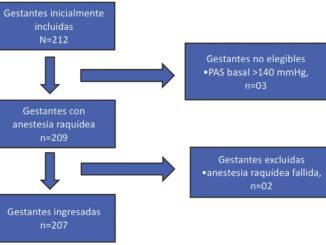

This prospective cohort observational study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the National University of Colombia (act No. 011-191-17) and the Ethics and Research Committee of the Maternal and Child Institute – Subred Centro Oriente (act No. 231 of November 27, 2017). It was conducted at the Maternal and Child Institute in Bogotá, where data were collected between November 2017 and 2018. Pregnant patients over 18 years old who underwent cesarean section with tubal ligation, cesarean section alone, or tubal ligation alone, all under spinal anesthesia, were included. Patients in critical condition with mechanical ventilation, postoperative neurological complications, pre-existing chronic pain, or those undergoing simultaneous surgeries were excluded.

Using a statistical power of 80%, an expected correlation of 0.5, a two-tailed hypothesis, and a significance level of 0.05, a minimum sample size of 56 participants was calculated[9]. Adjusting for a 20% non-response rate, a total of 73 participants were required. A form with three categories of information was used for prospective data collection: sociodemographic, clinical, and related to the surgical procedure and anesthesia. Follow-up was conducted from admission to the operating room until 48 hours after the surgical procedure. Postoperative pain intensity was measured upon admission to the post-anesthesia care unit, at 24 and 48 hours, using the numerical pain scale[10]. The collected physical data were stored in a file under the custody of the principal investigator. A Microsoft Excel® database was built for data processing and analysis, which was performed using the R programming language (R Foundation®).

The data were analyzed using descriptive statistics. Numerical variables were presented as means and standard deviations, while nominal and qualitative variables were expressed as absolute numbers and percentages. A bivariate analysis was performed to evaluate differences in pain levels between the different procedures (cesarean section, cesarean section with tubal ligation, and tubal ligation), using Fisher’s exact test[11], for categorical comparisons and the Wilcoxon test with continuity correction for ordinal variables[12]. In addition, Bonfer- roni correction was applied to adjust the significance values in multiple comparisons with a p-value of 0.017 for repeated measures comparison[13]. Bivariate results were considered statistically significant when the p-value was less than 0.05.

-

Results

In the analysis of sociodemographic and clinical data from the 73 patients, the average age was 26.5 ± standard deviation (SD) of 6.2, while the average body mass index (BMI) was 26.9 ± SD 3.9 kg/m2. Most procedures were tubal ligation (54.8%), followed by cesarean section (24.7%) and cesarean section with tubal ligation (20.5%). 82.2% of patients had between 1 and 3 previous pregnancies, and 90.4% had had between 1 and 3 vaginal deliveries. 52.1% of patients had no history of cesarean section, while 39.7% had had between 1 and 2 previous cesarean sections. Labor before the cesarean section occurred in only 21.2% of patients (Table 1).

For pre-cesarean analgesia, only 15.1% of patients received epidural anesthesia and 9.1% received intravenous anesthesia. The indication for cesarean section was elective in 72.3% of cases, while 27.7% were emergency cesarean sections. The most commonly used anesthetic technique was spinal anesthesia (98.6%), and in terms of neuroaxial opioids, an average of 19.2 ± 22.3 mcg of fentanyl and 54.5 ± 51.4 mcg of morphine were administered. The average surgical time was 32.2 ± 18 minutes, and intraoperative complications (hypotension, nausea, and vomiting) occurred in 6.8% of cases.

For intraoperative analgesia, the most frequently administered intravenous drug was diclofenac, which was used in 68.5% of patients, while 15.1% received dipyrone. In immediate postoperative analgesia, only 1.4% received diclofenac, and 43.8% received dipyrone. In terms of postoperative pain, 89% of patients reported no pain at 2 hours. At 24 hours, 13.7% of patients had no pain, and 20.5% had severe pain. At 48 hours, a similar distribution was observed, with only 12.3% having no pain, while 16.5% had severe pain.

In the bivariate analysis of pain levels in the post-anesthesia care unit (PACU) at 2 hours postoperatively, no statistically significant differences were found between the three types of procedures (cesarean section, cesarean section with ligation, and tubal ligation alone) at any of the observation times: 2, 24, and 48 hours (Table 2).

When comparing pain measurements at 2, 24, and 48 hours postoperatively, the Wilcoxon test with continuity correction was used, and applying the Bonferroni correction (p < 0.017), statistically significant differences were observed between pain levels at 2 hours and 24 hours (p < 0.01), as well as between 2 hours and 48 hours (p < 0.01). No significant differences were found in pain levels between 24 and 48 hours (p = 0.4094) (Figure 1).

Table 1. Sociodemographic and Clinical Characterization

Table 2. Bivariate analysis of pain and procedure

| Type of Procedure (Mean ± SD) | Pain in PACU | Value p | |||

| No Pain | 2 hours postoperatively Mild | Moderado | Severo | ||

| Cesarean section and Tubal Ligation | (1.1 ± 2.32) | 11 (73.3) | 2 (13.3) | 1 (6.7) | 1 (6.7) |

| Ligadura de trompas (0.2 ± 0.99) | 38 (95) | 1 (2.5) | 1 (2.5) | 0 (0) | |

| Cesarean section (4.2 ± 2.67) | 2 (11.1) | 24 hours postoperatively

5 (27.7) |

7 (38.9) | 4 (22.2) | 0.9685* |

| Cesarean section and Tubal Ligation | 3 (20) | 5 (33.3) | 4 (26.7) | 3 (20) | |

| (3.5 ± 2.77)

Tubal Ligation (4.1 ± 2.78) |

5 (12.5) | 15 (37.5) | 12 (30) | 8 (20) | |

| Cesarean section (3.9 ± 2.46) | 2 (11.1) | 48 hours postoperatively

6 (33.3) |

7 (38,9) | 3 (16,7) | 0.88* |

| Cesarean section and Tubal Ligation | 1 (6.7) | 4 (26.7) | 8 (53,3) | 2 (13,3) | |

| (4.2 ± 1.98)

Tubal Ligation (3.6 ± 2.39) |

6 (15) | 15 (37.5) | 12 (30) | 7 (17,5) | |

| PACU: Post-anesthesia care unit; *:Fisher’s exact test; SD: Standard deviation. | |||||

Figure 1. Distribution of pain at 2, 24, and 48 hours by procedure. Comparisons of pain levels at 2, 24, and 48 hours using the Wilcoxon test with continuity correction. Bonferroni correction (p < 0.0167) was applied to adjust the significance values with 3 comparisons. ****: The results showed statistically significant differences between pain levels at 2 hours and 24 hours (p < 0.01) and between 2 hours and 48 hours (p < 0.01): Ns: No significant difference was found between pain levels at 24 and 48 hours (p = 0.4094).

-

Discussion

This study showed that acute postoperative pain in the first 48 hours after the procedure does not vary significantly among patients undergoing cesarean section, cesarean section with tubal ligation, and tubal ligation alone. Two hours postoperatively, 89% of patients did not report pain, whereas at 24 hours, this percentage decreased to 13.7%, and 20.5% of patients reported severe pain. At 48 hours, only 12.3% of patients did not report pain, while 16.5% still experienced severe pain. These findings are consistent with previous studies indicating that postoperative pain in cesarean sections is a critical factor affecting recovery and patient satisfaction[14].

The bivariate analysis of pain levels between the three procedures showed that, at 2 hours, there were no statistically significant differences between the groups (p = 0.1037), reinforcing the idea that tubal ligation is not a procedure exempt from relevant postoperative pain. At 24 hours, no significant differences were found in pain levels among the three procedures (p = 0.9685), with mean pain scores of 4.2 for cesarean section, 3.5 for cesarean section with ligation, and 4.1 for tubal ligation. These data highlight the need to improve pain management strategies in all patients undergoing tubal ligation[15]. This suggests that postoperative pain does not depend on the procedure but on the time elapsed after surgery, which is consistent with existing literature on the evolution of postoperative pain in patients undergoing cesarean section and tubal liga- tion[16],[17].

This study presents some limitations that should be considered when interpreting the results. The relatively small sample size (n = 73) could affect the generalization of the results. However, the sample size calculation was adequate to maintain the accepted statistical power, aiming to reduce alpha and beta errors, thereby increasing the validity of the findings within this specific context. Another important limitation was the lack of long-term follow-up to assess the incidence of chronic postoperative pain, which is known to affect a significant percentage of women undergoing cesarean section. Future studies should explore different follow-up periods for patients undergoing tubal ligation to establish its association with potential persistent postoperative pain, with a larger sample size that could detect a statistical difference.

-

Conclusion

Acute postoperative pain did not show significant differences between cesarean section, cesarean section with ligation, and tubal ligation alone at 2 hours. However, there was an increase in pain intensity at 24 and 48 hours, highlighting the importance of postoperative pain management regardless of the surgical procedure.

Funding: This study has no funding source.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Dedication: To the professors of the Universidad Nacional de Colombia for their contributions to our education.

-

References

1. Betran AP, Torloni MR, Zhang JJ, Gülmezoglu AM; WHO Working Group on Caesarean Section. WHO Statement on Caesarean Section Rates. BJOG. 2016 Apr;123(5):667–70. https://doi.org/10.1111/1471-0528.13526 PMID:26681211

2. Zuleta-Tobón JJ. Evolución de la cesárea en Colombia y su asociación con la naturaleza jurídica de la institución donde se atiende el parto. Rev Colomb Obstet Ginecol. 2023 Mar;74(1):15–27. https://doi.org/10.18597/rcog.3901 PMID:36920899

3. Piva VM, Voget V, Nucci LB. Cesarean section rates according to the Robson Classification and its association with adequacy levels of prenatal care: a cross-sectional hospital-based study in Brazil. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2023 Jun;23(1):455. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-023-05768-2 PMID:37340447

4. Villar J, Valladares E, Wojdyla D, Zavaleta N, Carroli G, Velazco A, et al.; WHO 2005 global survey on maternal and perinatal health research group. Caesarean delivery rates and pregnancy outcomes: the 2005 WHO global survey on maternal and perinatal health in Latin America. Lancet. 2006 Jun;367(9525):1819–29. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68704-7 PMID:16753484

5. Adesiyun AG. Female sterilization by tubal ligation: a re-appraisal of factors influencing decision making in a tropical setting. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2007 Apr;275(4):241–4. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00404-006-0257-5 PMID:17021769

6. Cole LP, Colven CE, Goldsmith A. Tubal occlusion via laparoscopy in Latin America: an evaluation of 8186 cases. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 1979;17(3):253–9. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1879-3479.1979.tb00161.x PMID:42580

7. Gerbershagen HJ, Aduckathil S, van Wijck AJ, Peelen LM, Kalkman CJ, Meissner W. Pain intensity on the first day after surgery: a prospective cohort study comparing 179 surgical procedures. Anesthesiology. 2013 Apr;118(4):934–44. https://doi.org/10.1097/ALN.0b013e31828866b3 PMID:23392233

8. Stourač P, Kuchařová E, Křikava I, Malý R, Kosinová M, Harazim H, et al. Establishment and evaluation of a post caesarean acute pain service in a perinatological center:retrospective observational study. Ces Gynekol. 2014 Nov;79(5):363–70. PMID:25472454

9. Cohen J. A power primer. Psychol Bull. 1992 Jul;112(1):155–9. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.112.1.155 PMID:19565683

10. Breivik H, Borchgrevink PC, Allen SM, Rosseland LA, Romundstad L, Hals EK, et al. Assessment of pain. Br J Anaesth. 2008 Jul;101(1):17–24. https://doi.org/10.1093/bja/aen103 PMID:18487245

11. Kim HY. Statistical notes for clinical researchers: chi-squared test and Fisher’s exact test. Restor Dent Endod. 2017 May;42(2):152–5. https://doi.org/10.5395/rde.2017.42.2.152 PMID:28503482

12. Fagerland MW, Sandvik L. The Wilcoxon-Mann-Whitney test under scrutiny. Stat Med. 2009 May;28(10):1487–97. https://doi.org/10.1002/sim.3561 PMID:19247980

13. Armstrong RA. When to use the Bonferroni correction. Ophthalmic Physiol Opt. 2014 Sep;34(5):502–8. https://doi.org/10.1111/opo.12131 PMID:24697967

14. Duan G, Yang G, Peng J, Duan Z, Li J, Tang X, et al. Comparison of postoperative pain between patients who underwent primary and repeated cesarean section: a prospective cohort study. BMC Anesthesiol. 2019 Oct;19(1):189. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12871-019-0865-9 PMID:31640565

15. Manjunath AP, Chhabra N, Girija S, Nair S. Pain relief in laparoscopic tubal ligation using intraperitoneal lignocaine: a double masked randomized controlled trial. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2012 Nov;165(1):110–4. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejogrb.2012.06.035 PMID:22819575

16. Borges NC, Silva BC, Pedroso CF, et al. Dolor postoperatorio en mujeres sometidas a cesárea. Enferm Glob. 2017;16(48):354–83. https://doi.org/10.6018/eglobal.16.4.267721.

17. Jankelevich A, Carmona C, Gutiérrez R, Reyes F, Ásfora C, Oñate G, et al. Dolor Crónico Post Cesárea, un problema desconocido. Rev Chil Anest. 2022;51(6):783–7. [cited 2024 Sep 29] https://doi.org/10.25237/revchilanestv5130111514.

ORCID

ORCID