Gabriel de Sousa MD.1,2,3, Luiza Lino MD.1,2, Felipe Alves MD.1,2, Anderson Goncalves MD.1,2, Ricardo Carlos MD, PhD.1,2, Vinicius Caldeira Quintäo MD, MSc, PhD1,2*

Recibido: 18-08-2025

Aceptado: 17-09-2025

©2025 El(los) Autor(es) – Esta publicación es Órgano oficial de la Sociedad de Anestesiología de Chile

Revista Chilena de Anestesia Vol. 54 Núm. 5 pp. 551-557|https://doi.org/10.25237/revchilanestv54n5-10

PDF|ePub|RIS

Construyendo un currículo basado en competencias en anestesia pediátrica en América Latina

Abstract

Pediatric anesthesia training in Latin America remains heterogeneous, marked by disparities in infrastructure, educational frameworks, and subspecialty recognition. With rising surgical demand and evolving perioperative challenges, aligning training with competency-based models is crucial. This narrative review draws on international guidelines, regional experiences in Brazil, Chile, Colombia, and Mexico, and global curriculum frameworks to propose strategies for harmonizing pediatric anesthesiology education. We highlight structural gaps, curricular priorities, and opportunities for regional collaboration toward a unified, context-sensitive competency-based model that responds to both global standards and local realities.

Resumen

La formación en anestesia pediátrica en América Latina sigue siendo heterogénea, marcada por disparidades en infraestructura, marcos educativos y reconocimiento de la subespecialidad. Con el aumento de la demanda quirúrgica y la evolución de los desafíos perioperatorios, resulta crucial alinear la formación con modelos basados en competencias. Esta revisión narrativa se apoya en guías internacionales, experiencias regionales en Brasil, Chile, Colombia y México, y marcos curriculares globales para proponer estrategias que permitan armonizar la educación en anestesiología pediátrica. Destacamos brechas estructurales, prioridades curriculares y oportunidades de colaboración regional hacia un modelo unificado, sensible al contexto, basado en competencias, que responda tanto a los estándares globales como a las realidades locales.

-

Introduction

The safe and effective administration of anesthesia in pediatric patients necessitates a particular understanding of age-specific physiological and pharmacological principles, as well as the unique psychosocial dimensions of caring for children. Anesthesiologists must be adept at addressing a broad spectrum of pediatric-specific challenges, ranging from the complexities of neonatal airway management to effective perioperative communication with families[1]. However, across much of Latin America, pediatric anesthesia is frequently administered by general practitioners whose training includes minimal formal exposure to pediatric subspecialties[2]. This situation reflects deep-rooted structural disparities in medical education systems, unequal allocation of healthcare resources, and longstanding deficiencies in strategic workforce develop- ment[3].

The adoption of competency-based medical education (CBME) offers an opportunity to reform training in a way that prioritizes defined outcomes, formative feedback, and learner autonomy[4]. CBME has become the preferred model for postgraduate training in many high-income countries, replacing traditional time-based approaches[5]. Its key features-entrustable professional activities (EPAs), milestones, and real-time assess- ments-ensure that trainees acquire and demonstrate essential competencies before transitioning to unsupervised practice[6]. In pediatric anesthesiology, where clinical precision and team coordination are vital, this model is especially relevant.

Although CBME principles are increasingly accepted, their implementation in Latin America remains inconsistente[2]. This review examines the region’s current landscape, focusing on Brazil, Chile, Colombia, and Mexico, and proposes strategies for developing a regionally adapted, competency-based curriculum.

-

The Latin American landscape

Latin America comprises over 600 million people across highly diverse healthcare systems[7],[8]. In Brazil, pediatric anesthesia is not formally recognized by the Federal Medical Council, despite its clinical relevance[9]. Fellowship programs in pediatric anesthesia have emerged in large tertiary centers, such as Hospital das Clínicas, Faculdade de Medicina, Universi- dade de Sao Paulo (HCFMUSP) and Hospital Pequeño Príncipe, offering one-year training experiences[10]. However, pediatric exposure during residency remains limited, especially in institutions without specialized children’s hospitals[11]. As a result, anesthesiologists often graduate with minimal practical experience in managing neonates, syndromic patients, or advanced airway cases.

In Chile, the landscape is similarly fragmented. An estimated 20 anesthesia residency programs operate nationally, most of which include pediatric rotations. However, only one formal fellowship exists, and the demand for highly trained pediatric anesthesiologists exceeds supply[10]. To address the training gap, temporary solutions-such as one-month refresher courses and six-month placements organized through the World Federation of Societies of Anaesthesiologists (WFSA)-have been ad- opted[12]. These initiatives, while helpful, might be insufficient to sustain long-term workforce development[13].

Mexico has achieved greater institutionalization of pediatric anesthesia as a subspecialty. The National Council for Certification in Anesthesiology (CNCA) has accredited ten two-year fellowships in university hospitals, and formal board certification is available. Nonetheless, fewer than 300 anesthesiologists are board-certified in pediatric anesthesia nationally. Barriers include inadequate financial compensation, regional concentration of programs, and limited mentorship in non-urban areas[10].

Pediatric anesthesia in Colombia is not formally recognized as a distinct subspecialty, and the majority of pediatric surgical procedures are still delivered by general anesthesiologists with variable exposure to pediatric training during residency[2]. Specialized pediatric anesthesia fellowships remain limited to a few university-affiliated hospitals in major cities such as Bogotá and Medellín, creating disparities in access to subspecialized care across the country. National pediatric surgical programs, particularly in oncology, orthopedics, and congenital malformations, have highlighted the increasing demand for pediatric anesthesiologists. However, resource limitations and uneven distribution of trained providers continue to challenge the development of a structured national curriculum. Recent efforts by academic centers and the Colombian Society of Anesthesiology have focused on strengthening continuing education, simulationbased training, and regional collaborations to address gaps in pediatric perioperative safety[14].

Across all these countries, training pathways differ in duration, structure, and accreditation. This lack of standardization contributes to persistent inequalities in the preparation of pediatric anesthesia providers, with significant implications for patient safety and workforce distribution[15] (Figure 1).

-

Global competency frameworks

International organizations have made significant progress in defining competencies for pediatric anesthesiologists. The Society for Pediatric Anesthesia (SPA), through a structured Delphi process, produced a comprehensive framework identifying key clinical areas, such as neonatal anesthesia, congenital cardiac disease, advanced airway management, anesthesia outside the operating room (OR), and regional techniques under ultrasound guidance. In addition to technical domains, the SPA consensus underscores the importance of non-clinical competencies: leadership, communication, patient safety, quality improvement, education, and research literacy[16].

Simulation-based education constitutes a foundational component of this educational framework. High-fidelity simulations enable the realistic replication of critical clinical scenarios-such as pediatric anaphylaxis or challenging neonatal intubation- thereby allowing trainees to develop technical and cognitive skills within a risk-free environment[17]. These are effectively complemented by low-fidelity simulations and case-based discussions, which reinforce clinical reasoning, decision-making, and interprofessional collaboration. Integral to this pedagogical approach is structured debriefing, which fosters reflective practice and facilitates the identification of areas for continuous improvement[18].

The European Society of Anaesthesiology and Intensive Care (ESAIC), in collaboration with the European Society for Paediatric Anaesthesiology (ESPA), has promoted similarly rig-

orous standards[19]. Their curriculum proposes tiered training: core pediatric skills for all anesthesiologists, and advanced training for those specializing in pediatrics. Portfolios, logbooks, and standardized assessments form the backbone of their evaluation strategy.

These frameworks are not without challenges. Implementation requires robust faculty training, institutional commitment, and adequate infrastructure. Nonetheless, they provide a blueprint for regional adaptation in Latin America, where variability in training and resources is significant[11].

Figure 1. Main challenges in Pediatric Anesthesia Education in Latin America.

-

Gaps in Latin American programs

Latin American training programs face numerous deficits that undermine consistent skill acquisition. Evaluation methods are often informal, relying on case counts or subjective faculty impressions[20]. Structured assessment tools-such as EPAs, direct observation instruments, and multisource feedback-are rarely used, making it difficult to ensure that all graduates meet minimum standards of clinical competence[2].

Clinical exposure among trainees is markedly heterogeneous. While those training in high-volume pediatric centers may encounter complex surgical cases, individuals based in general hospitals frequently lack access to high-acuity pediatric scenarios. Subspecialty areas such as neonatal anesthesia, pediatric cardiac anesthesia, and advanced regional techniques are particularly underrepresented in many training environ- ments[21]. This disparity in clinical experience contributes to variability in competency development and poses a potential risk to patient safety.

Non-technical skills remain a blind spot. In modern healthcare, anesthesiologists must function as team leaders, educators, communicators, and system thinkers. Yet few Latin American curricula include formal instruction in these areas. Simulation-based team training, root-cause analysis of critical incidents, and quality improvement projects are rarely embedded in educational structures[22].

Another major concern is faculty readiness. Many clinical educators have no formal training in CBME methods, and limited time is allocated for teaching, mentorship, or curriculum development. Institutions often lack incentive structures to support academic contributions. These limitations hinder the ability to implement sustainable and effective training programs[23].

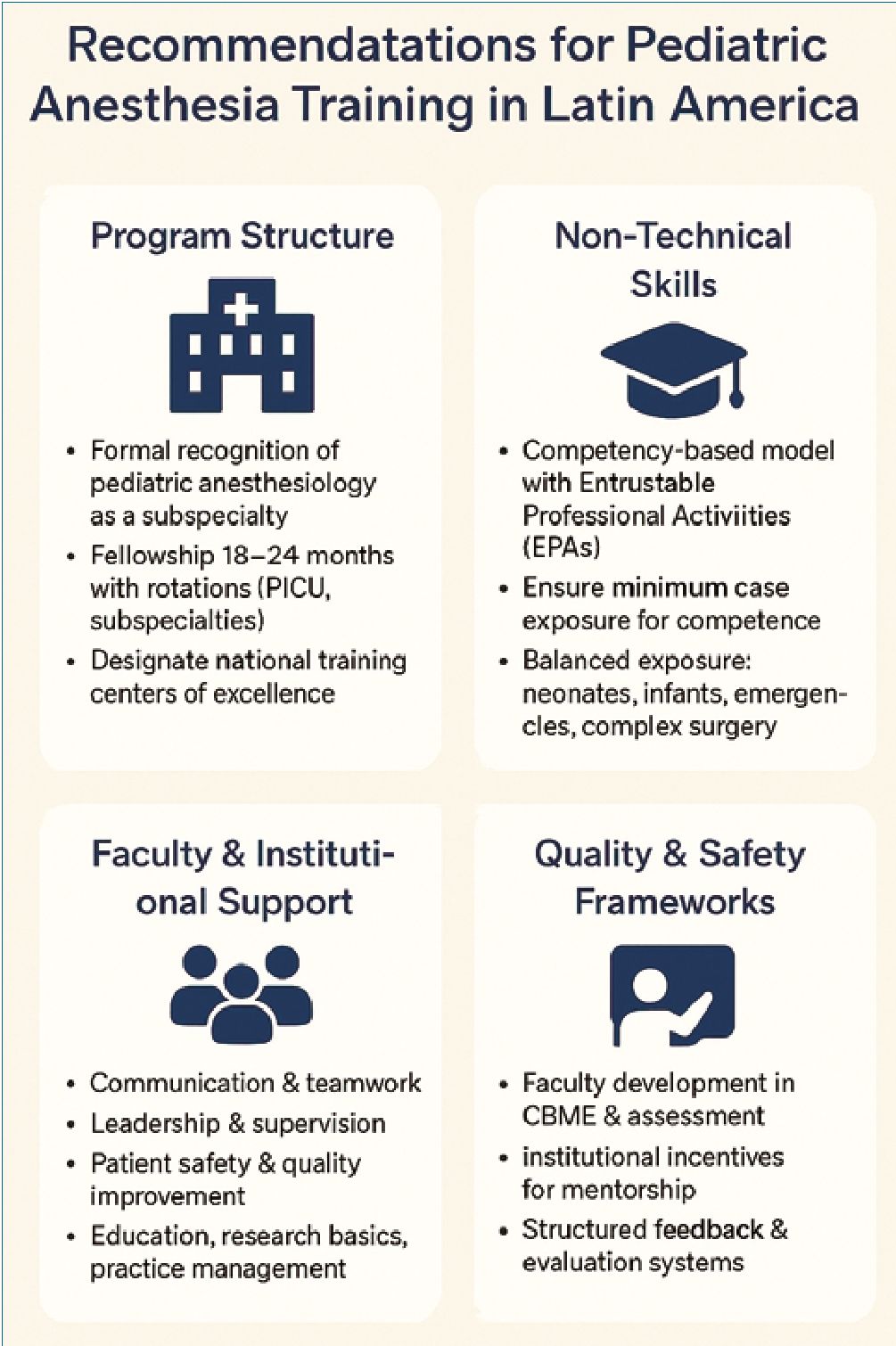

Lastly, pediatric anesthesia fellowships remain concentrated in metropolitan areas. As a result, many regions-especially in rural or resource-constrained areas-lack access to pediatric- trained professionals[24]. This not only exacerbates healthcare inequities but also limits the reach of educational initiatives. The recommendations for pediatric anesthesia training in Latin America are summarized in the Figure 2.

-

Strategic directions for curriculum reform

Transforming pediatric anesthesia education in Latin America requires a multi-pronged approach. A regional core curriculum should be established, drawing on global frameworks but tailored to local needs. This curriculum must define clinical and non-clinical competencies, establish progression milestones, and incorporate diverse assessment tools. Core areas might include neonatal physiology, pediatric pharmacology, airway management, ultrasound-guided blocks, ethical decision-making, and perioperative communication[5]

Simulation should be a foundational component. It allows standardization of rare but critical scenarios and promotes interprofessional learning. In low-resource areas, low-cost simulators or role-playing exercises can be equally effective. The integration of simulation into national curricula must be accompanied by faculty training and institutional investment.

Curriculum design should be collaborative. Ministries of health, academic leaders, national societies, and local educators must work together to ensure that training reflects public health priorities, epidemiological patterns, and available resources. Regional and national task forces could oversee curriculum implementation, monitor outcomes, and provide feedback loops for continuous improvement.

Importantly, equity must be prioritized. Programs should invest in distance learning, tele-mentoring, and rotating faculty models to expand training opportunities beyond large academic centers. Partnerships between well-established programs and smaller or rural institutions can promote shared growth and mutual learning.

-

Implementing and sustaining CBME

To implement CBME effectively, institutions must move beyond procedural quotas and focus on observable professional activities. EPAs should be contextualized for pediatric practice in Latin America, with clear descriptions of supervision levels and expected behaviors. Faculty must be trained to conduct real-time observations and provide structured, actionable feed- back[25].

Assessment tools such as the Mini Clinical Evaluation Exercise, Objective Structured Clinical Examinations (OSCEs), simulation checklists, and narrative evaluations should be deployed across the training timeline. Digital platforms can facilitate documentation, feedback delivery, and portfolio management. These systems also allow program directors to monitor progress, identify learners in difficulty, and tailor remediation strate- gies[26].

Simulation must be strategically used not just for technical skills but also for evaluating communication, decision-making, and crisis management. Shared simulation cases across coun- tries-adjusted for language and epidemiology-can facilitate benchmarking and joint quality improvement.

Figure 2. Main recommendations for Pediatric Anesthesia Training in Latin America.

Faculty development is critical. Educators must understand CBME theory, assessment principles, and feedback strategies. Regional societies can lead faculty training efforts, offering blended learning courses, mentorship programs, and recognition awards. Institutional policies should protect time for teaching, recognize academic contributions, and reward innovation.

CBME should be understood not as a discrete initiative, but as a foundational framework guiding all phases of professional development-from residency and fellowship training to lifelong continuing medical education. Harmonizing postgraduate curricula with national certification standards and ongoing professional development systems is essential to ensure coherence, long-term sustainability, and the continuous advancement of clinical competence[27].

-

Accreditation and quality assurance

A reliable accreditation system is essential for ensuring the quality and consistency of pediatric anesthesia training across Latin America. Current national accreditation frameworks, such as the CNCA in Mexico or the collaboration between the Brazilian Society of Anesthesiology (SBA) and the Sao Paulo Society of Anesthesiology (SAESP) in Brazil, offer valuable starting points[10]. However, these systems vary widely in scope, criteria, and enforcement. To promote harmonization and shared benchmarks, the region would benefit from a unified, transparent accreditation framework aligned with competency-based principles.

This regional accreditation model should establish minimum standards for curriculum structure, faculty qualifications, simulation capacity, case exposure, and evaluation methods. Accreditation should not only assess whether programs cover a sufficient number of pediatric cases but also evaluate the complexity of cases encountered, the quality of supervision, and the extent to which EPAs and milestones are integrated into training[28].

A modernized case log system is essential. Rather than simply recording the number of cases, logs should track patient age groups, comorbidities, techniques used, and procedural acuity. For instance, managing anesthesia for a healthy child undergoing a hernia repair should be documented differently than providing care for a syndromic neonate undergoing thoracic surgery. This approach provides a more meaningful picture of trainee experience and readiness[29].

Peer review should be incorporated into the accreditation process. Site visits conducted by trained educators from within the region can offer objective evaluations, facilitate mutual learning, and foster regional solidarity. These visits can assess infrastructure, review teaching and assessment practices, and provide recommendations for program improvement. Structured self-assessment reports prepared by each institution can complement site visits, fostering a culture of reflection and accountability.

The use of digital dashboards can significantly enhance the efficiency and transparency of accreditation. These platforms can aggregate data on EPA completion, simulation participation, assessment frequency, and trainee satisfaction, allowing programs to monitor progress in real time and benchmark against regional peers. Institutions should also track long-term outcomes such as graduate placement, board certification pass rates, and retention in pediatric practice settings.

Crucially, accreditation should be viewed as a longitudinal process rather than a one-time evaluation. Periodic re-accreditation cycles, supported by ongoing data collection and feedback loops, can help ensure that programs evolve alongside changes in clinical practice, educational evidence, and population needs.

-

Faculty development and mentorship

High-quality education depends on high-quality educators. In pediatric anesthesia, where both technical proficiency and emotional intelligence are essential, the role of faculty extends far beyond teaching procedures. Faculty must guide learners through complex ethical dilemmas, foster interprofessional collaboration, model patient-centered communication, and support professional growth[19].

Despite the growing emphasis on educational quality, many training programs in Latin America lack formal faculty development frameworks. Clinicians frequently assume teaching responsibilities without prior training in pedagogical theory, curriculum development, or assessment methodologies. Moreover, institutional support for medical educators is often limited, with few programs offering protected academic time or formal recognition for teaching excellence. These gaps not only hinder the effectiveness of instruction but also contribute to diminished faculty engagement and increased risk of burnout.

A deliberate, multi-tiered faculty development strategy is needed. Introductory workshops on CBME principles, simulation facilitation, and structured feedback should be made widely accessible-ideally in both in-person and virtual formats. More advanced training in mentorship, curriculum leadership, and educational research should be available for experienced faculty. Regional anesthesiology societies can support this through certification programs, educator tracks at conferences, and collaboration with international partners.

Mentorship must also be formalized within training programs. While informal mentorship often occurs organically, structured programs with defined roles, goals, and meeting schedules have been shown to improve mentee satisfaction and career progression. Faculty should be trained not only to supervise clinical tasks but to support academic productivity, personal development, and leadership aspirations. Institutions should recognize mentorship contributions in promotion criteria and workload planning.

Leadership development represents a critical yet frequently overlooked dimension of medical education. Faculty must be prepared to navigate institutional dynamics, advocate for the allocation of educational resources, and effectively represent the interests of pediatric anesthesia in national policy discussions. Targeted training in strategic planning, conflict resolution, and high-impact communication is essential to cultivate future program directors, professional society leaders, and influential voices in health policy[30].

Academic promotion systems must evolve to acknowledge the increasingly multifaceted roles of medical educators. Contributions to curriculum design, faculty development, educational innovation, and program evaluation should be valued on par with traditional scholarly outputs such as peer-reviewed publications and research funding. Without formal recogni-

tion of these activities, educational leadership risks remaining undervalued, thereby compromising its long-term viability and impact within academic institutions.

International partnerships offer additional opportunities. Faculty exchanges, co-supervised fellowships, remote lectureships, and twinning arrangements with global centers of excellence can enhance local capacity and foster innovation. These collaborations should be guided by principles of equity and mutual benefit, ensuring that local educators retain ownership of curricula and contextually adapt imported models.

-

Regional collaboration and capacity building

Latin America’s shared linguistic, cultural, and historical context provides a unique opportunity to foster regional collaboration in pediatric anesthesia education. While countries differ in healthcare structure and economic development, they face common challenges-unequal access to training, concentration of resources in urban centers, and limited recognition of pediatric anesthesia as a subspecialty. Rather than reinventing the wheel within each country, regional cooperation can accelerate progress and optimize resource use.

One of the most impactful steps would be the co-creation of a Latin American pediatric anesthesia competency framework. This document, developed by a regional working group and endorsed by national societies, could define essential clinical and non-clinical competencies, outline suggested EPAs, and provide guidance on assessment strategies. While respecting national autonomy, it would promote alignment and enable mutual recognition of training across borders[31].

Collaborative educational initiatives hold significant transformative potential[32]. The co-development of bilingual online learning modules, regionally tailored simulation scenarios, and standardized assessment rubrics-hosted on accessible digital platforms-could greatly enhance training across diverse settings. Such shared resources would be especially impactful for smaller or under-resourced programs, promoting equitable access to high-quality educational materials and fostering regional academic cohesion.

Cross-institutional activities-such as virtual case discussions, regional journal clubs, and simulation-based competitions-can foster peer learning, professional networks, and a shared educational culture[33]. Faculty development can also benefit from regional collaboration, with experienced educators mentoring newer programs through on-site or virtual support.

Research collaborations represent another powerful mechanism for advancing the field[34]. Multicenter studies investigating perioperative outcomes, anesthesia-related adverse events, and the implementation of CBME frameworks can generate critical data to inform clinical practice, support evidence-based advocacy, and enhance the academic visibility of the region on the global stage. The LASOS-Peds initiative, for instance, has demonstrated the feasibility and value of collaborative data collection in Latin America[35].

Advocacy efforts can also be more effective when coordinated regionally. Whether pushing for formal recognition of pediatric anesthesia, increased funding for training programs, or regulatory support for CBME, a unified voice carries more weight. Organizations such as WFSA or SPA can play a facilita- tive role, helping to coordinate efforts, secure technical support, and represent Latin American interests in global forums[36].

Ultimately, regional collaboration is not just a practical strat- egy-it is a moral imperative. By sharing expertise, aligning standards, and supporting each other’s growth, countries across Latin America can ensure that all children, regardless of where they live, receive safe and high-quality anesthesia care.

-

Conclusion

Pediatric anesthesia in Latin America is at a pivotal moment. The region has made important strides in expanding training programs and embracing modern educational concepts. Yet significant gaps persist-in curriculum standardization, faculty development, equitable access, and assessment quality. The consequences are tangible: children in many parts continue to receive anesthesia from providers without specialized training, exposing them to unnecessary risks.

Competency-based medical education offers a compelling path forward. Grounded in defined outcomes, formative feedback, and progressive autonomy, CBME aligns with the complexity of pediatric care and the evolving role of the anesthesiologist. Its implementation, however, must be carefully adapted to the Latin American context. A one-size-fits-all model imported from high-income countries will not succeed without local adaptation, faculty ownership, and institutional commitment.

To realize the promise of CBME, the region must invest in faculty training, develop robust accreditation systems, and build infrastructure for simulation and assessment. Collaboration across countries is essential. Shared frameworks, joint resources, and multicenter research can accelerate capacity building and foster a culture of excellence. National societies, ministries of health, universities, and international partners each have a role to play.

What is needed now is collective vision and sustained action. A harmonized, high-quality training system in pediatric anesthesia is not only feasible-it is urgent. By preparing future anesthesiologists to meet the highest standards of clinical care, communication, and leadership, Latin America can ensure that every child receives the safe, compassionate, and expert care they deserve.

Satement: This manuscript has not been submitted to any other journal and has not been previously published. The authors declare that no funding was received for this work. All authors declare no conflicts of interest. We hereby assign the intellectual property rights of this article to the Revista Chilena de Anestesia.

-

References

1. Habre W. Pediatric anesthesia after APRICOT (Anaesthesia PRactice In Children Observational Trial): who should do it? Curr Opin Anaesthesiol. 2018 Jun;31(3):292–6. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACO.0000000000000580 PMID:29443725

2. Cabrera Hernández JS, Reinoso Chávez N. Current situation of pediatric anesthesiology training in Colombia. Colombian Journal of Anesthesiology. 2024 Apr 2; https://doi.org/10.5554/22562087.e1109.

3. Rocha TA, Vissoci J, Rocha N, Poenaru D, Shrime M, Smith ER, et al.; Global Initiative for Children’s Surgery. Towards defining the surgical workforce for children: a geospatial analysis in Brazil. BMJ Open. 2020 Mar;10(3):e034253. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2019-034253 PMID:32209626

4. Snell JJ, Lockman JL, Suresh S, Chatterjee D, Ellinas H, Walker KK, et al. Pediatric Anesthesiology Milestones 2.0: An Update, Rationale, and Plan Forward. Anesth Analg. 2024 Mar;138(3):676–83. https://doi.org/10.1213/ANE.0000000000006381 PMID:36780299

5. Kaur B, Taylor EM. Development of a pediatric anesthesia fellowship curriculum in Australasia by the Society for Pediatric Anesthesia of New Zealand and Australia (SPANZA) education sub committee. Paediatr Anaesth. 2023 Feb;33(2):100–6. https://doi.org/10.1111/pan.14536 PMID:35876724

6. Kealey A, Naik VN. Competency-Based Medical Training in Anesthesiology: Has It Delivered on the Promise of Better Education? Anesth Analg. 2022 Aug;135(2):223–9. https://doi.org/10.1213/ANE.0000000000006091 PMID:35839492

7. Vissoci JR, Ong CT, Andrade L, Rocha TA, Silva NC, Poenaru D, et al.; Global Initiative for Children’s Surgery. Disparities in surgical care for children across Brazil: use of geospatial analysis. PLoS One. 2019 Aug;14(8):e0220959. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0220959 PMID:31430312

8. Demographic Observatory of Latin America and the Caribbean 2024. Population Prospects and Rapid Demographic Changes in the First Quarter of the Twenty-first Century in Latin America and the Caribbean. 2024.

9. Quintão VC, Carlos RV, de Sousa GS, Carmona MJ. Mind the gap between low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) and high-income countries (HICs): fostering pediatric anesthesia globally. Braz J Anesthesiol. 2024;74(5):844544. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bjane.2024.844544 PMID:39089425

10. Quintão VC, Concha M, Argüello LA, Cavallieri S, Cortinez LI, de Sousa GS, et al. Pediatric anesthesiology in Brazil, Chile, and Mexico. Paediatr Anaesth. 2024 Sep;34(9):858–65. https://doi.org/10.1111/pan.14886 PMID:38619275

11. Módolo NS, Cumino DO, Lima LC, Barros GA. Advancing pediatric anesthesia in Brazil: reflections on research and education. Braz J Anesthesiol. 2024;74(5):844535. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bjane.2024.844535 PMID:38936800

12. Cavallieri S, Cánepa P, Campos M. Evolution of the WFSA education program in Chile. Paediatr Anaesth. 2009 Jan;19(1):33–4. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1460-9592.2008.02881.x PMID:19076500

13. Evans FM, Duarte JC, Haylock Loor C, Morriss W. Are Short Subspecialty Courses the Educational Answer? Anesth Analg. 2018 Apr;126(4):1305–11. https://doi.org/10.1213/ANE.0000000000002664 PMID:29547425

14. Lopez MJ, Amaya S, Albornoz E, Hernandez JS. Pediatric Anesthesiology in Colombia. Paediatr Anaesth. 2025 May;35(5):404–5. https://doi.org/10.1111/pan.15085 PMID:39960143

15. Schifino Wolmeister A, Hansen TG, Engelhardt T. Challenges of organizing pediatric anesthesia in low and middle-income countries. Braz J Anesthesiol. 2024;74(5):844525. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bjane.2024.844525 PMID:38906364

16. Ambardekar AP, Eriksen W, Ferschl MB, McNaull PP, Cohen IT, Greeley WJ, et al. A Consensus-Driven Approach to Redesigning Graduate Medical Education: The Pediatric Anesthesiology Delphi Study. Anesth Analg. 2023 Mar;136(3):437–45. https://doi.org/10.1213/ANE.0000000000006128 PMID:35777829

17. Daly Guris RJ, George P, Gurnaney HG. Simulation in pediatric anesthesiology: current state and visions for the future. Curr Opin Anaesthesiol. 2024 Jun;37(3):266–70. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACO.0000000000001375 PMID:38573191

18. Manyumwa P, Chimhundu-Sithole T, Marange-Chikuni D, Evans FM. Adaptations in pediatric anesthesia care and airway management in the resource-poor setting. Paediatr Anaesth. 2020 Mar;30(3):241–7. https://doi.org/10.1111/pan.13824 PMID:31910309

19. Hansen TG, Vutskits L, Disma N, Becke-Jakob K, Elfgren J, Frykholm P, et al.; Safetots Initiative (www.safetots.org). Harmonising paediatric anaesthesia training in Europe: proposal of a roadmap. Eur J Anaesthesiol. 2022 Aug;39(8):642–5. https://doi.org/10.1097/EJA.0000000000001694 PMID:35822223

20. Echeverry P. Reflexion about Pediatrics, Anesthesia and Education in Pediatric Anesthesia in Colombia and South America. Pediatr Neonatal Nurs. 2015 Apr;2(1):37–42. https://doi.org/10.17140/PNNOJ-2-107.

21. Lopez-Barreda R, Schaigorodsky L, Rodríguez-Pinto C, Salas W, Muñoz Y, Betanco B, et al. Barriers to healthcare access for children with congenital heart disease in eight Latin American countries. Paediatr Anaesth. 2024 Sep;34(9):893–905. https://doi.org/10.1111/pan.14880 PMID:38515426

22. Mathis MR, Janda AM, Yule SJ, Dias RD, Likosky DS, Pagani FD, et al. Nontechnical Skills for Intraoperative Team Members. Anesthesiol Clin. 2023 Dec;41(4):803–18. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anclin.2023.03.013 PMID:37838385

23. Fraser AB, Stodel EJ, Jee R, Dubois DA, Chaput AJ. Preparing anesthesiology faculty for competency-based medical education. Can J Anaesth. 2016 Dec;63(12):1364–73. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12630-016-0739-2 PMID:27646528

24. Salinas-Torres VM, Salinas-Torres RA, Cerda-Flores RM, Martínez-de-Villarreal LE. Prevalence, Mortality, and Spatial Distribution of Gastroschisis in Mexico. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2018 Jun;31(3):232–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpag.2017.12.013 PMID:29317257

25. Hansen TG. Specialist training in pediatric anesthesia – the Scandinavian approach. Paediatr Anaesth. 2009 May;19(5):428–33. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1460-9592.2009.02932.x PMID:19236599

26. Boyer TJ, Ye J, Ford MA, Mitchell SA. Modernizing Education of the Pediatric Anesthesiologist. Anesthesiol Clin. 2020 Sep;38(3):545–58. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anclin.2020.06.005 PMID:32792183

27. Weiss M, Vutskits L, Hansen TG, Engelhardt T. Safe Anesthesia For Every Tot – The SAFETOTS initiative. Curr Opin Anaesthesiol. 2015 Jun;28(3):302–7. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACO.0000000000000186 PMID:25887194

28. Desjardins G, Cahalan MK. Subspecialty accreditation: is being special good? Curr Opin Anaesthesiol. 2007 Dec;20(6):572–5. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACO.0b013e3282f18bd8 PMID:17989552

29. Ambardekar AP, Furukawa L, Eriksen W, McNaull PP, Greeley WJ, Lockman JL. A Consensus-Driven Revision of the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education Case Log System: Pediatric Anesthesiology Fellowship Education. Anesth Analg. 2023 Mar;136(3):446–54. https://doi.org/10.1213/ANE.0000000000006129 PMID:35773224

30. Lockman JL, Schwartz AJ, Cronholm PF. Working to define professionalism in pediatric anesthesiology: a qualitative study of domains of the expert pediatric anesthesiologist as valued by interdisciplinary stakeholders. Paediatr Anaesth. 2017 Feb;27(2):137–46. https://doi.org/10.1111/pan.13071 PMID:28101983

31. Journal C, Cecilia P, Marín E. Revista Colombiana de Anestesiología The new challenges in pediatric anesthesia in Colombia Los nuevos retos de la Anestesia Pediátrica en Colombia [Internet]. 2016. Available from: http://www.congresoscare.com.co/cali/agenda/1er-congreso-

32. Morriss WW, Milenovic MS, Evans FM. Education: The Heart of the Matter. Anesth Analg. 2018 Apr;126(4):1298–304. https://doi.org/10.1213/ANE.0000000000002653 PMID:29547424

33. Putnam EM, Baetzel AE, Leis A. Paediatric anaesthesiology education: simulation-based ‘attending boot camp’ for fellows shows feasibility and value in the early years of attendings’ careers. BJA Open. 2022 Dec;4:100115. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bjao.2022.100115 PMID:37588785

34. Quintão VC, Carmona MJ. A call for more pediatric anesthesia research. Braz J Anesthesiol. 2021;71(1):1–3. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bjane.2020.12.001 PMID:33712245

35. Quintão VC, de Sousa GS, Torborg A, Vieira A, Consonni F, Rodrigues S, et al. Latin American Surgical Outcomes Study in Paediatrics (LASOS-Peds): study protocol and statistical analysis plan for a multicentre international observational cohort study. BMJ Open. 2024 Sep;14(9):e086350. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2024-086350 PMID:39313281

36. Coté CJ. The WFSA pediatric anesthesia fellowships: origins and perspectives. Paediatr Anaesth. 2009 Jan;19(1):31–2. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1460-9592.2008.02867.x PMID:19076499

ORCID

ORCID