Marisol Zuluaga Giraldo1*, Simón Galindo Zuluaga2, Susan M. Goobie3

Recibido: 19-08-2025

Aceptado: 20-09-2025

©2025 El(los) Autor(es) – Esta publicación es Órgano oficial de la Sociedad de Anestesiología de Chile

Revista Chilena de Anestesia Vol. 54 Núm. 5 pp. 632-634|https://doi.org/10.25237/revchilanestv54n5-19

PDF|ePub|RIS

Manejo de la sangre en el paciente perioperatorio: un nuevo estándar de atención para pacientes pediátricos

Abstract

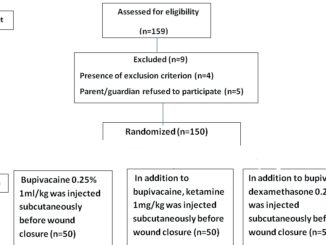

Perioperative Patient Blood Management (PBM) is an evidence-based, patient-centered approach increasingly recognized as the standard of care in pediatric surgery. Although blood transfusion save lives, it carries higher risks in children, including immunomodulation, organ dysfunction, prolonged hospitalization, and increased costs. Preoperative anemia, particularly common in low- and middle-income countries, is a predictor of perioperative transfusion and adverse outcomes. PBM is based on three pillars: optimizing red cell mass, minimizing perioperative blood loss, and improving tolerance to anemia. Strategies include early anemia detection, iron supplementation, restrictive transfusion thresholds, intraoperative blood conservation techniques, antifibrinolytic therapy, cell saver, normovolemic hemodilution, Surgical, anesthetic methods and goal-directed transfusion guided by viscoelastic testing and massive hemorrhage protocols. Massive perioperative hemorrhage remains a leading cause of morbidity and preventable cardiac arrest in children, particularly in complex surgeries such as trauma, cardiac procedures, scoliosis, craniosynostosis, and liver transplantation. Effective management requires early recognition of high-risk patients, restrictive transfusion strategies, meticulous surgical hemostasis, and goal-directed interventions guided by viscoelastic testing and massive hemorrhage protocols. Novel approaches, such as artificial intelligence and machine learning, may further enhance inventory management and predict transfusion needs. Importantly, pediatric transfusion practices must consider unique physiological requirements, avoiding simple extrapolation from adult thresholds. Postoperative management emphasizes minimizing iatrogenic blood loss, adhering to institutional guidelines, and applying multimodal, physiology-guided strategies. PBM improves safety, reduces unnecessary transfusions, conserves resources, and enhances outcomes in pediatric perioperative care. Implementation requires multidisciplinary collaboration and institutional commitment.

Resumen

La Gestión de Sangre del Paciente Perioperatorio (PBM) es un enfoque basado en la evidencia y centrado en el paciente, cada vez más reconocido como el estándar de atención en la cirugía pediátrica. Aunque las transfusiones de sangre salvan vidas, conllevan mayores riesgos en los niños, incluyendo la inmunomodulación, la disfunción orgánica, la hospitalización prolongada y el aumento de costos. La anemia preoperatoria, particularmente común en los países de ingresos bajos y medios, es un predictor de transfusión perioperatoria y resultados adversos. La PBM se basa en tres pilares: optimización de la masa de glóbulos rojos, minimización de la pérdida de sangre perioperatoria y mejora de la tolerancia a la anemia. Las estrategias incluyen la detección temprana de la anemia, la suplementación de hierro, los umbrales restrictivos de transfusión, las técnicas de conservación de sangre intraoperatoria, la terapia antifibrinolítica, el recuperador de sangre, la hemodilución normovolémica, Métodos quirúrgicos, anestésicos y transfusión dirigida por objetivos guiada por pruebas viscoelásticas y protocolos de hemorragia masiva. La hemorragia perioperatoria masiva sigue siendo una de las principales causas de morbilidad y paro cardíaco prevenible en niños, particularmente en cirugías complejas como trauma, procedimientos cardíacos, escoliosis, craneosinostosis y trasplante de hígado. La gestión efectiva requiere el reconocimiento temprano de pacientes de alto riesgo, estrategias de transfusión restrictivas, hemostasia quirúrgica meticulosa e intervenciones dirigidas por objetivos guiadas por pruebas viscoelásticas y protocolos de hemorragia masiva. Enfoques novedosos, como la inteligencia artificial y el aprendizaje automático, pueden mejorar aún más la gestión de inventarios y predecir las necesidades de transfusión. Es importante que las prácticas de transfusión pediátrica consideren los requisitos fisiológicos únicos, evitando la simple extrapolación de los umbrales adultos. El manejo posoperatorio enfatiza la minimización de la pérdida sanguínea iatrogénica, la adherencia a las directrices institucionales y la aplicación de estrategias multimodales guiadas por la fisiología. La PBM mejora la seguridad, reduce las transfusiones innecesarias, conserva recursos y mejora los resultados en el cuidado perioperatorio pediátrico. La implementación requiere colaboración multidisciplinaria y compromiso institucional.

Throughout the centuries and in all civilizations and cultures there has been a mysterious and magical link between life and blood; Blood transfusion has undoubtedly saved millions of lives and has been one of the great contributions to modern medicine. However, some aspects surrounding its safety have changed this concept, which, instead of being a solution, is now part of a problem. Evidence is emerging that suggests that the risks of blood transfusion go beyond the more commonly known infectious and metabolic complications, especially in critically ill pediatric patients. Those non-infectious risks include allergic reactions, immunomodulation, and hemolysis. Leukocytes and inflammatory mediators present in blood products have been implicated in blood transfusion-induced immunomodulatory response (TRIM). TRIM is associated with increased risk of nosocomial infection, multiple organ dysfunction, and death in critically ill patients. These risks have been associated with an increases in days in the intensive care unit, hospital length of stay, and morbidity and mortality.

In 2012, the American Medical Association and the Joint Commission National Summit on Overuse identified blood transfusion as one of the most important health care-related overuse issues facing the world. Blood is a precious resource, evident now more than ever, with global critical blood shortages.

SHOT (Serius Hazards of Transfusion) is a national audit system of transfusion practice in England; it reports that adverse effects are 3 times more frequent in children than in adults and more than 80% of cases It is due to the transfusion of incorrect blood components due to lack of medical knowledge about some special requirements in children such as the indications for leukoreduced, irradiated, washed or fresh components[1] (Table 1).

Furthermore, with an aging population, a significant reduction in blood bank stocks is anticipated, which will force medicine to operate without allogeneic blood transfusions in many scenarios. Additionally, allogeneic blood transfusions represent high costs for healthcare systems when we account for their production, transport, storage, and hospital administration. This cost burden is borne not only by the public healthcare system per unit of blood but also by private healthcare entities. The prolonged hospital stays and morbidities associated with allogeneic blood transfusions further increase these costs.

The risks of transfusion therapy, high costs, progressive decrease in donors in some countries and evidence of increased morbidity and mortality, have spured the adoption of a more judicious use of blood products with evidence-based transfusions.

Multiple studies in adults have shown that in elective surgeries the need for a perioperative blood transfusion can be predicted in 98% of cases analyzing 3 parameters that include preoperative hemoglobin concentration, estimated blood loss and transfusion threshold[2]. In children the main risk factors for perioperative transfusion include: young age (neonates and infants have a lower blood volume, making them more susceptible to transfusion even with minimal blood loss) preoperative anemia; comorbidities (especially patients with congenital cardiac defects, pulmonary diseases), hemoglobinophaties, type or complexity of surgery (liver transplant, neurosurgery, cardiovascular, spinal, orthopedic surgery, trauma), low body weight and higher ASA score.

Patient Blood Management (PBM) involves the timely and multidisciplinary application of evidence-based multimodal medical and surgical concepts and is founded on three key pillars, which aim to optimize and improve red blood cell (RBC) mass by: treating and preventing preoperative and iatrogenic anemia (Pillar 1); minimizing surgical, procedural, and iatrogenic blood loss while optimizing coagulation (Pillar 2); and maximizing patient-specific physiological tolerance of anemia and coagulopathy using restrictive transfusion thresholds (Pillar 3) [3]-[8].

Unlike adults, pediatric patients have unique physiological characteristics and medical needs that necessitate specialized approaches to PBM.

Pediatric PBM optimizes a child’s own blood health, minimizes unnecessary transfusions, and employs age/weight-specific conservation strategies. Neonates, infants, children, and adolescents each have distinct physiological responses to blood loss and transfusion, requiring individualized management based on total blood volume, hemodynamic stability, and developmental differences in coagulation and metabolism[9],[10].

The evolution of patient blood management (PBM) from a transfusion-centered approach (focused on the use of blood components) to a patient-centered approach (focused on supporting the patient’s overall blood health) has provided major improvements in health care delivery, patient outcomes, patient satisfaction, preservation of resources, and cost savings has recently been defined by an international expert PBM committee as a “patient-centered, systematic, evidence-based approach to improve patient outcomes by managing and preserving a patient’s own blood, while promoting patient safety and empowerment. In 2010, the World Health Organization (WHO) recommended that all member states implement multidisciplinary and multimodal PBM strategies to improve outcomes for patients. More recently, in 2025, the WHO published a policy brief titled “The Urgent Need to Implement Patient Blood Management”; it noted that the PBM paradigm has not been universally employed.

The World Health Organization (WHO) has called for implementation of PBM as a global standard of care. The WHO policy statement, ‘The Urgent Need to Implement PBM’, is an appeal to transform awareness into implementation. This call for action creates a sense of urgency for healthcare entities to implement PBM, ‘a systematic, multidisciplinary, multi-professional concept to routinely minimise risk factors, and, in so doing, significantly and cost-effectively improve health and clinical outcomes for hundreds of millions of medical and surgical patients, pregnant women, neonates, children, adolescents, older patients, and the population as a whole’.

Patient blood management (PBM) is a personalized, evidence-based, multidisciplinary strategy to optimize blood health, improve patient outcomes and reduce unnecessary exposure to blood and blood products[11].

Table 1. Patien blood management in children

| Preoperative | Intraoperative | Postoperative |

| Preoperative History | Fluid Management (avoid hemodilution) | Restrictive Tranfusion |

| Detect – Investigate anemia (3-6 weeks before elective Surgery) | Careful Blood Pressure | Consider Point of Care Testing |

| Consider postponing elective major Surgery to optimize Haemoglobin in high risk patients | Restrictive transfusión1 | Avoid Hypothermia, Hemodilution, Acidosis3 |

| Erithropoiesis stimulation to maximise red blood cells | Optimize Hemostatic Surgical Tecnique2 | Minimize iatrogenic blood loss |

| Treat Iron deficiency | Avoid Hypothermia, Acidosis, Hemodilution3 | Limit rutin blood draws and volumes |

| Risk stratification of bleeding assesment tool | Goal directed Transfusions protocols4 | Consider Antifibrinolytics |

| Consider minimally invasive tecniques | Use Point of Care Testing (TEG-ROTEM )5 | Optimize Cardiac output, ventilation, and oxygenation |

| Optimize cardiovascular, respiratory, hematological, renal comorbidities | Consider Topical Hemostatics Agents6 | Minimize Oxygen consuption |

| Optimize organ oxygenation and perfusión | Consider Cell Saver

Consider Concentrate Factor7 Consider Antifibrinolytics8 Consider Patient Position9 Consider Tourniquet10 |

|

| 1Restrictive transfusión strategy: patients haemodynamically stable suggest haemoglobin >7.0 g /dL except neonates, cyanotic cardiac disease, pulmonary disease or actively bleeding (Hb > 8 g/dL).

2Optimising surgical technique, local vasoconstrictors, meticulous surgical technique, cautery, minimally invasive surgery, preoperative surgical planning with 3D models, and preoperative embolisation. 3Avoid Hypothermia; for each decrease in temperature below 36oC, there is 10% decrease in coagulation factors. 4Goal-directed transfusion protocols such as massive haemorrhage management pathways. If active uncontrolled bleeding and hemodynamic instability consider fixed ratio transfusion( MTP) until patient is stabilized and then transition to goal directed strategy. 5Point-of-care testing includes viscoelastic testing such as thromboelastography (TEG) or rotational thromboelastometry (ROTEM). 6Topical coagulation products include gelatine sponges (Gelfoam), Surgicel, Avitene, topical thrombin preparations, fibrin glue/fibrin sealant (products that combine thrombin and fibrinogen such as Crosseal that contains fibrinogen, thrombin, and TXA, Floseal, Evicel) and topical antifibrinolytics. 7Recombinant coagulation products include fibrinogen concentrate and prothrombin complex concentrates. 8Antifibrinolitics: tranexamic acid bolus 10-30 mg/kg and infusion 5-10 mg /kg/h. 9Patient position simple and effective intervention to reduce intraoperative bleeding:reverse Trendelenburg reduce blood loss in craneal surgery, endoscopic sinus surgery. Prone position: free abdomen; decrease of compression inferior vena cava in scoliosis surgery. 10Tourniquet: minimize intraoperative bleeding in extremity surgeries , improve surgical field visibility, reduces operative time, increase postoperative pain. |

||

-

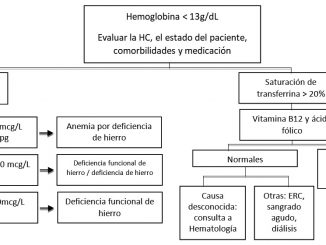

What do we know about the preoperative anemia in children?

Anaemia is an underappreciated and underestimated global public health issue affecting billions worldwide. Preoperative anaemia is preventable and manageable in the paediatric patient. For patients who are undergoing an elective procedure or surgery and have weeks before their scheduled surgery date, iron deficiency anaemia often can either be corrected or mitigated before the day of surgery.

Anaemia among children in low- and middle-income countries (LIMC) is a significant global health concern as highlighted by the World Health Organisation (WHO). Several factors such as malnutrition, infections, parasitic infections, haemoglobinopathies, and HIV or chronic illness contribute to this wide-spread issue. Haemoglobinopathies are of particular importance in LMICs, with 80% of children born each year with this condition. Various socio economic factors, including poverty, antenatal care, provision of iron supplementation in pregnancy, maternal diet in pregnancy, familial level of education, poor preventive measures for malaria, and rural location contribute to the high prevalence of anaemia in children in LMICs. The analysis of the South African Paediatric Surgical Outcomes Study in patients with aged between 6 months and < 16 years, who underwent elective and non elective noncardiac surgery and had a preoperative hemoglobin recorded found that In children in whom a preoperative Hb was recorded 46.2% had preoperative anemia. Preoperative anemia was independently associated with an increased risk of any postoperative complication and preoperative anemia an independent predictor of intraoperative blood transfusion[12].

The WHO estimates approximately 40% of children in the under 5 years age group are anaemic. This has inevitable consequences on a child’s development and long-term blood health. In neonates, anemia is associated with poor feeding, neonatal infection, intensive care unit admission, neurocognitive alterations, increased risk of attention deficit and hyperactivity disorder, increased risk of autism spectrum disorder, and perinatal mortality. In children and adolescents, iron deficiency with or without anemia is associated with impaired cognition and cognitive development. Hence, the prevalence of pediatric anemia is highest in the most vulnerable populations and is underrecognized and under-treated by pediatricians and the medical community.

Anemia in neonates and children is independently associated with a two fold increase in morbidity compared to matched cohorts undergoing non-cardiac surgery in the United States, independent of blood transfusions[13]. Furthermore, preoperative anemia is an independent predictor of intraoperative blood transfusion and is associated with postoperative complications including increased mortality, length of stay in hospital and intensive care units, surgical site infections, and diminished quality of life[13].

The Advancement of Patient Blood Management Pediatric and Neonatal Medicine recommends state Don’t proceed with non-emergent major surgery until anemia is evaluated and treated. Since iron deficiency anemia is the most common etiology of preoperative anemia, expert consensus guidelines recommend screening for anemia at least 3-6 weeks before major elective surgery[14]. Expert consensus suggests postponing elective surgery to optimise preoperative haemoglobin (Hb) unless the surgery is classified as urgent.

Iron deficiency anaemia as a result of poor diet is the most common aetiology of preoperative anaemia. The US prevalence of iron deficiency anaemia in children 1-5 yr of age is estimated to be 1-2%, and as high as 15% depending on ethnicity and socio-economic status. First-line treatment for patients who have at least 4-6 weeks before surgery is oral iron replacement. If dose-appropriate replacement is adhered to with good compliance, this approach is expected to increase the Hb concentration by at least 1 g /dl over 4-6 weeks. The typical dose of oral iron is 2-6 mg kg/day Gastrointestinal side-effects are seen in 15-30% of children, along with a reported unpleasant metallic taste[8],[15],[16].

Erythropoietin is currently recommended to optimize red blood cell mass for those at risk for significant blood loss and where transfusion of allogeneic blood product is not an accepted option within a bloodless programme. Recombinant human erythropoietin alpha (EPO) has demonstrated safety and efficacy in numerous studies to reduce the need for allogenic transfusion[17].

Several studies have reported improved outcomes with preoperative EPO administration, however dosing was expectedly variable in terms of amount and frequency 300 to 600 U/kg (most use 600) on a weekly or biweekly basis, typically for 3 weeks. Adjunctive ferrous sulfate supplementation (2-6 mg/ kg/d) should be inlcuded in a RBC optimization EPO protocol. There is ongoing research investigating the utilization of preoperative EPO with elemental iron supplementation in children undergoing craniosynostosis surgery.

Recombinant human erythropoietin (EPO) given subcutaneously weekly for 3-6 weeks prior to surgery in select patients with supplemental Iron, folic acid, B12 vitamin, and E vitamin can increase the preoperative Hct by 28-56% and decrease transfusion requirements[16],[18]-[24].

-

How can we decrease the intra-operative blood loss?

Intraoperative blood loss is an independent predictor of morbidity and mortality.

Bleeding caused by trauma or major surgery, which requires massive transfusion, is one of the main causes of preventable morbidity and mortality in pediatric patients. Hypovolemia secondary to blood loss has been reported as the number one cause of cardiovascualr mortality perioperatively and prevetable[25]. Critical bleeding management requires preparation, and a protocoled, goal directed therapeutic approach. The two main causes of perioperative bleeding inlcude surgical bleeding attributed to a failure to control bleeding from blood vessels at the surgical site, or because surgery is performed in highly vascularized tissues that are not easily cauterized, such as occurs in scoliosis surgery or correction of craniosynostosis. Meticulous surgical hemostasisand proper patient selection with colloborative preparation and management contribute to reduce the risk of bleeding.

Another consideration is non-surgical or hemostatic bleeding that presents as generalized bleeding at venipuncture sites, through the nasogastric tube, through the surgical wound margins and the presence of hematuria. Its etiology may be due to: 1) A pre-existing coagulation disorder not diagnosed before surgery; 2) Coexistence of previous diseases that are associated with dysfunction of coagulation or platelet factors, such as chronic kidney disease, liver disease, malignant disease (Wilms tumor) and the use of medications; 3) Alteration of hemostasis related to the surgical procedure, as occurs in cardiac surgery under extracorporeal circulation or liver transplantation with all the changes in the hemostatic system in different phases of surgery; 4) Massive blood loss in major or trauma surgery[26].

It has been estimated that 60-90% of children undergoing major surgery (e.g., liver transplant, cardiac surgery, and cranial surgery) receive blood transfusion[27].

Early identification of patients at high risk of bleeding and adequate treatment of massive bleeding and its consequences are vital to reduce morbidity and mortality in pediatric patients. The management strategies forperioperative bleeding in children are included in Table 2[28].

Surgery itself alters coagulation by multiple mechanisms that include hyperadrenergic responses, hyperfibrinolysis, and consumptive coagulopathy. In most routine surgical procedures on infants and children, the orchestration of procoagulant, anticoagulant, fibrinolytic, and vascular endothelial responses is sufficiently balanced to prevent pathological bleeding or thrombosis. However, when invasive procedures cause significant vascular endothelial injury, exposure of blood to non-endothelial surfaces, or altered hemodynamics, life-threatening bleeding and/or thrombosis can occur.

Representative clinical scenarios with increased rates of bleeding are cardiac surgery with cardiopulmonary bypass, liver transplant, cranial and scoliosis surgery, severe trauma, which triggers increased bleeding. It is essential to consider the different hemostatic changes depending on the procedure to adopt different treatment strategies. A-depth knowledge of the patient’s risk factors, the hemostatic changes that occur depending on the type of surgery, and adequate knowledge of the surgical technique can help predict perioperative bleeding and determine the extent of prophylactic measures to avoid allogeneic transfusion, and allow preparation for correct replacement of blood losses[29],[30].

Table 2. The management of the perioperative bleeding in children

| 1. Identify patients at risk of bleeding (preventive) |

| 2. Understand the physiological hemostatic changes in pediatric patients and the hemostatic changes related to the surgical procedure |

| 3. Preparation for the surgical procedure |

| 4. Reduce allogeneic transfusions through Patient Blood Management |

| 5. Correct replacement of blood losses: protocol in massive bleeding and restrictiva transfusión strategy |

| 6. Prevent and early treat complications caused by massive transfusión |

| 7. Pharmacological therapy |

| 8. Consider the usefulness of the different coagulation tests and limitations |

-

Preoperative preparation

Preparation for the surgical procedure include:

1. Evaluate the clinical history and patient’s clinical status including timely preoperative anemia screening and management.

2. Consider the estimated blood volume according to age and weight, and the permissible blood losses.

3. Preoperative planning and collaborative between the anesthesia and surgical team to discuss the risk of blood loss and blood conservation techniques.

4. Communication with the blood bank (for special requirements).

5. If the pateint is less than one year of less than 10 kg or if there is a risk of massive transfusion in any age, request packaged erythrocytes with less than a 1 week of collection or washed to reduce the potassium load. Hyperkalemia is one of the most feared complications in massive transfusions, particularly in children[31].

5. Monitoring (invasive, arterial gases, coagulation) and venous access based on expected blood losses.

6. Avoid hypothermia, hemodilution, acidosis.

The coagulopathy of hypothermic patients includes dysregulation of coagulation enzyme processes, platelet function, activation of fibrinolysis, and endothelial injury.

All available active warming methods should be applied in all surgical procedures[32],[33].

-

Reduce allogeneic transfusions through patient blood management

Intraoperative blood conservation strategies using evidence-based restrictive transfusion protocols guided by hemodynamic stability and monitoring for impaired end-organ oxygen delivery is a critical component of pediatric PBM. Allogeneic blood transfusion, once considered an essential therapeutic measure for anaemia and blood loss, carries the risk of increased morbidity and mortality in a dose-dependent relationship. Therefore, harnessing restrictive management strategies, including optimal blood use, limits blood transfusion by administering the right component, in the right dose, to the right patient, at the right time, for the right reason, and is an important measure of PBM succes. Intraoperative techniques to minimize blood loss may be broadly categorized into surgical methods or no pharmacological methods such acute normovolemic hemodilution (ANH), cell salvage and pharmacological interventions (Table 3).

-

Anesthesia methods

Acute normovolemic hemodilution (ANH) has been described for both adult and pediatric surgeries in which high blood loss is anticipated. ANH under anesthesia is the removal of whole blood from the patient before surgical incision while maintaining normovolemia by infusing crystalloids or colloids as needed. It reported in paediatric cardiac surgery , scoliosis, orthopedic and maxillofacial surgery, in which high blood loss is anticipated. The goal of this procedure is to reserve a safe supply of fresh autologous whole blood while maintaining adequate hemoglobin Hb concentration and hemodynamics. The whole blood may be reinfused over the course of the surgery to maintain stable hemodynamics with the remaining blood administered near the end of surgery. Whole blood is collected using a syringe or blood bag containing anticoagulant in a 1 to 7 ratio of blood and Anticoagulant Citrate Dextrose Adenin Solution. Up to 20% of the patient’s circulating blood volume may be collected as tolerated. The volume drawn is also dependent on the patient’s starting hematocrit. Exact recommendations for

hemodilution targets and fluid replacement ratios should take into account the individual patient and surgical characteristics, and vary widely between patients and surgeries. For example, replacement volumes must account for the variability of perioperative intravascular depletion based on NPO times, projected insensible losses, metabolic requirements, and other unique patient characteristics;due to the volume of blood removed, adequate venous access is required. Hypotension must be avoided and may limit collection volume. The anesthesiologist should calculate the allowable blood loss based on the starting Hb and the post ANH Hb target. Autologous blood must be collected in labeled, designated whole blood storage bags, and is stored at room temperature for 8 h and up to 24 h when stored in a cooler between 2°C and 6°C. Storage of red cells at ~4°C decreases the metabolic rate of the cell and enables blood to be stored for longer periods. When returned to the patient, whole blood should be given via a 170-260 pm filter set while utilizing a blood infusion warmer.

Table 3. Surgical methods

| 1. Meticulous surgical technique including staging of compfex surgery |

| 2. Preoperative emboiization of highly vascularized lesions (lnterventional radiological embolization of the tumors vascular blood supply prior to resection has become a mainstay of the management of some tumors and has improved patient outcome |

| 3. Minimally invasive surgical methods (laparoscopic and robotic surgeries) |

| 4. Electrocoagufation devices such as argon |

| 5. Miniaturization of CPB circuits In cardiac surgery have also been a successful strategy especially for newborns and small infants. |

| 6. Reducing CVP in liver surgery has been an important strategy in mlnimizíng blood loss. A reduction in CVP of 30% of the initial valué is desirable in the hepatectomy phase during liver transplant or in resection of liver tumors |

| 7. Patient position |

| 8. Use of tourniquet |

This technique is useful in patients undergoing surgery in which substantial blood loss is anticipated and blood component replacement will be needed. The use of ANH may avoid or decrease allogeneic blood component transfusions. The advantages of ANH include (1) reduction in blood viscosity which improves oxygen transport especially to the microcirculation; (2) blood lost during surgery will contain less RBCs per volume; (3) ability to transfuse whole blood, containing functional platelets and coagulation factors, back to patient after bleeding has slowed down or subsided; (4) another advantages; low cost compared to other blood conservation techniques, easy and quick to do it, does not require laboratory testing, minimum risk of transfusion errors,not storage injuries.

Acute normovolemic hemodilution requires an adequate RBC mass to start, making it unsuitable for emergencies, patients with preexisting cardiac or pulmonary disease, hematologic disorders such sickle cell anemia, infants with small blood volumes or those who are severely anemic or hypovolemic[34]-[36]. ANH is more labor-intensive for the anesthesia team than traditional transfusion practice[37].

Autologous salvaged blood; is an important method of Red Blood Cell (RBC) conservation that should be used as a part of a multimodal paediatric PBM strategy. Expert consensus recommendations, observational reports, and prospective research suggest that utilising cell salvage decreases RBC transfusion in infants, children, and adolescents undergoing craniosynostosis, liver transplant, spinal, and cardiac surgical procedures. Children with 10 kg who lose more than 10% of their total blood volume benefit from cell salvage.

Equipment specific for paediatrics such as smaller collection bowls and specific collection and washing strategies (high-quality wash) allows this technique to be used even in neonates. In addition, erythrocyte washing may reduce inflammatory biomarkers and systemic inflammation. NATA guideline recommends the use of cell salvage in pediatric cardiac surgery to reduce perioperative transfusion[38],[39].

Pharmacologic intervention include ; vasoconstrictors, topical hemostatic agents including fibrin/thrombin gel, systemic hemostatic agents, antifibrinolytics,factor concentrates.

Antifibrinolytic drugs such as tranexamic acid (TXA) is a synthetic lysine analog that competitively inhibit the activation of plasminogen to plasmin, thus preventing fibrinolysis. TXA may also have anti-inflammatory effects by reducing vasoactive peptide release. At higher doses, TXA is a direct inhibitor of plasmin and conse-quently an indirect inhibitor of all pathways activated by plasmin (e.g., platelets, complement, inflammation). It is excreted in the urine largely unchanged, with filtration inversely proportional to plasma creatinine. Large doses of TXA have the potential to promote thrombosis and, due to its ability to pass the blood-brain barrier, can cause central nervous system hyperexcitability (seizures) by blocking the action of the inhibitory neurotransmitters gamma-aminobutyric acid and glycine[40].

Strong evidence suggests that administration of tranexamic acid perioperatively can reduce blood loss and the need for transfusion in children. The tranexamic acid should be considered in all children undergoing surgery where there is a risk of substantial bleeding. This method could be a relatively safer, simpler, and cost-efficient approach for patient blood management in comparison to transfusion and would be invaluable in LMICs where other facilities are not well established. tranexamic acid have been shown to reduce blood transfusion in cardiac, orthopedic, scoliosis and cranial remodeling surgeries in children[41]-[44].

Studies of pharmacokinetic modeling and simulation suggest a TXA dosing regimen of between 10 and 30 mg/ kg loading dose (maximum 2 g), followed by between 5 and 10 mg/ kg/h maintenance infusion rates to maintain TXA plasma concentrations between 20 and 70 ug/ml for pediatric surgeries and trauma patients[45].

Absolute contraindications for antifibrinolytics include known hypersensitivity, active thromboembolic disease and fibrinolytic conditions with consumption coagulopathy Relative contraindications include renal impairment (dose adjust), disorders of thrombosis, pre-existing coagulopathy or use of oral anticoagulants. TXA is not contraindicated in children with a seizure disorder given the growing evidence supporting the safety profile of therapeutic dosing regimens. TXA-associated seizures have been reported in high-risk pediatric cardiac surgery patients with high doses (eg, 100 mg/kg). The reported TXA-associated seizure incidence for non-cardiac pediatric surgery is extremely low. In pediatric craniofacial surgery, the incidence of seizures with antifibrinolytics is comparable to the incidence reported in children not exposed to TXA[46].

Prophylactic administration of TXA is considered an essential component of an effective perioperative PBM strategy and expert consensus guidelines recommend TXA to be considered for all pediatric patients undergoing high blood loss surgery[47]-[49].

-

Appropriate management of intraoperative blood loss

The objectives in the intraoperative bleeding to identify and control the source of bleeding, minimize blood loss, restore tissue perfusion, and achieve hemodynamic stability and prevent coagulopathy. The goal in fluid management should include maintaining normovolemia, avoiding hypervolemia, and minimizing edema and hemodilution. Hemodilution can lead to dilutional anaemia and coagulopathy when RBCs and clotting factors are not replaced in a balanced resuscitation strategy; this causes a bleeding diathesis and should be avoided. Diagnosis and management of coagulation derangements to target appropriate allogeneic haemostatic product use (plasma, platelets, cryoprecipitate) can be accomplished using individualised multimodal strategies. These include using algorithm-based transfusion guidelines, point-of-care viscoelastic testing, goal-directed massive haemorrhage protocols (MHPs), and preferential treatment with pharmacological haemostatic agents or factor concentrates[50].

-

Goal directed massive hemorrhage and massive transfusion protocols

Blood; is an indispensable resource, yet it is becoming increasingly scarce. At the same time the transfusion of foreign blood is associated with risks for recipients if there is inadequate indication for its use. For this reason, a rational approach to the use of allogeneic blood transfusions is recommended in all areas of medicine and encouraged by the World Health Organization (WHO).

Implementation of standardized transfusion protocols is a simple, inexpensive, and effective strategy to safely minimize transfusion. Moreover, there is a body of scientific evidence demonstrating efficacy. Standardized transfusion thresholds have been shown to reduce red blood cell transfusion without an increased incidence of adverse events in adult patients and critically ill children and in pediatric postoperative patients.

The guideline from the “European Society of Anaesthesiology and Intensive Care” (ESAIC) for “severe perioperative bleeding” is opposed to transfusion if the child is hemodynamically stable and the Hb concentration is at least 7 g/dL. The decision to transfuse RBC concentrates should not only be based on laboratory results but should also depend on the child’s clinical condition and take risks and advantages of transfusion into account. Identification of “safe” hemoglobin thresholds for children is extremely important in practical anesthesia and perioperative medicine, it is also, and especially, true for pediatric patients that a transfusion decision should never be made solely on the basis of the Hb value. Oxygen supply and demand, lactate levels, regional oxygen saturation as well as the hemodynamic and respiratory status should, together with other parameters, be considered for the decision-making process[51].

In children with hemorrhagic shock, it is recommended to transfuse RBCs, plasma, and platelets empirically in ratios between 2 : 1 : 1 and 1 : 1 : 1. Pediatric patients with massive hemorrhage or active critical bleeding should be managed with a goal-directed massive hemorrhage protocol which may include a ratio driven, balanced resuscitation strategy, until the child is stabilized, and the bleeding is controlled. These recommendations exclude patients with acute brain injury, oncologic disease, stem cell transplantation, sickle cell anemia, severe acute respiratory distress syndrome, mechanical support, or cardiac disease, who may require a higher Hb.

Administration of therapeutic plasma is indicated for active bleeding with coagulopathy , abnormal viscoelastic point-of- care testing, perioperative or peri-procedural 1.5-fold increase in activated partial thromboplastin time (aPTT), and is an essential component of massive transfusion. Regardless of age and laboratory parameters, therapeutic plasma should not be administered as protection against bleeding; with the following exceptions: before major surgery and for severe coagulation imbalance. Its prophylactic administration, for example, to correct laboratory abnormalities, is contraindicated. Therapeutic plasma should not be used for volume replacement[52].

The decision to transfuse platelets should be based on the platelet count and function with VET (viscoelastic testing) and the patient’s clinical status. Platelet transfusion volume should be calculated based on weight and desired increase in platelet increment. The decision to transfuse, fresh frozen plasma, platelets and cryoprecipitate should be based on the etiology of the coagulopathy, clinical of bleeding and point-of-care viscoelastic testing[53].

Hypofibrinogenemia is an important risk factor for bleeding in clinical settings, including pediatric surgery. Fibrinogen reference ranges are 150-300 mg/dL in infants and newborns, some studies recommend keeping levels at least around 150-200mg/ dL for craniofacial surgeries. The decision to supplement fibrinogen firstly relies on adequate measurement of fibrinogen and there are many pitfalls around the optimal fibrinogen measurement in children. Cryoprecipitate and fibrinogen concentrate both effectively restore fibrinogen levels, but each product has its own set of advantages and constraints specific to use in children. In children, dosing for therapeutic cryoprecipitate indications should be calculated at least taking into account the child’s weight. Most pediatric transfusion guidelines dose cryoprecipitate based on the child’s weight as a single variable. Many advise doses of 5 to 10 mL/kg, with exceptions of 20 mL/ kg for the treatment of congenital fibrinogen deficiency with pathogen-reduced cryoprecipitate. Fibrinogen concentrate is dosed by most clinical guidelines in 50 to 70mg/Kg. There remains considerable uncertainty in children of all ages around optimal fibrinogen levels and the best fibrinogen replacement strategies[54].

Evidence for the use of PCC in pediatrics is weak. PCC contains factors II, VII, IX, and X, the vitamin K dependent factors, and can be given to pediatric patients undergoing invasive surgery who are receiving vitamin K antagonists. There is no evidence of efficacy, safety, or dosing of PCCs in pediatric patients. The use of PCCs is reported in those receiving CPB for cardiac surgery[55],[56] (Table 4).

Table 4. Perioperative management of perioperative bleeding in children

| Activate Institutional Pediatric Massive Transfusión Protocol |

| Obtain optimal vascular access (big and short catheter) |

| Controlled resuscitation until hemorraghe control has been stablished (hypotensive resuscitation is not recommended in children) |

| Maintain Hemodynamic and Volume status with crystalloid, colloids, blood products and vasopressors. Employ restrictive transfusion strategy Goal postoperative RBC transfusion should be HB 9.5 g/dL – avoid overtransfuision Avoid Ringer Lactate in Traumatic Brain Injury |

| Administer blood products and crystalloids per Kilogram Avoid fluid overload and haemodilution |

| If active uncontrolled bleeding and hemodynamic instability consider fixed ratio transfusion( MTP) until the patient is stabilized and then transition to goal directed strategy Consider RBC:PFC:Platelets = 2:1:1 or 1:1:1

Use un-crossmatched 0 negative RBC and AB+ plasma until Crossmatched blood is available Consider Intraoperative Blood Salvage (cell saver) Avoid risk of hiperkalemia , request RBC less than 1 week of recolection Watch for Hyperkalemia, if needed give calcium gluconate 60 mg/kg or calcium chloride 20 mg/kg IV |

| Prevention and treatment of Hypotermia, Hypocalcemia, Hyperkalemia |

| Blood products administration:

Use 140 micron filter for all products (except platelets) Use a blood warmer for RBC and FFP transfusión (NOT for platelets) Consider Use of rapid transfusión pumps in massive bleeding Monitor arterial blood gases, electrolytes and temperature Coagulation Monitoring. (TEG-ROTEM) |

| Consider Antifibrinolytics: Tranexamic acid IV bolus 10-30 mg/kg then 5-10 mg/kg/h IV infusion |

| Mantain Hemoglobin between 7-9 g/dl : Every 5 ml/kg of RBC increases Hb 1 g/dl |

| Platelets more than 50.000 mm3, more than 100.000 3i in Traumatic Brain Injury or active bleeding |

| Fibrinogen more tan 150 mg/dl: 10 ml/kg cryoprecipitate increases fibrinogen by 30-50 mg/dl |

-

Management of massive hemorrhage

Massive blood loss is defined as follows:

1. Loss of one blood volume in 24 h.

2. 50% loss of one blood volume in 3 h.

3. Losses over 1.5 ml/kg/min for 20 minutes.

4. Blood transfusion of over 40 ml/kg of red cells in 3 h.

5. Blood transfusion at a rate of 10% of total blood volume every 10 minutes.

Major blood losses should be acknowledged early, and the shock and its consequences, such as coagulopathy, must be treated promptly. Massive transfusion is associated with coagulopathy secondary to tissue trauma, hypoperfusion, dilution and coagulation factors, and platelets consumption. Dilution of coagulation factors and platelets is an important cause of coagulopathy in massively transfused patients. Hemodilution induces interstitial edema, disruption of microcirculation, and oxygenation, resulting in acidosis[57]-[59].

Hypothermia-induced coagulopathy is attributed to platelet dysfunction, reduced coagulation factors activity, and induction of fibrinolysis. Hypothermia induces platelet morphological changes and disrupts activation, adhesion, and aggregation. The enzyme cascade for coagulation factors is efficient if the temperature is above 35°C; there is a 10% decrease in the coagulation factors activity per every one degree of temperature decrease. The effect of hypothermia on in vivo coagulation is usually underestimated because the evaluations of the conventional coagulation tests are done at 37°C. In massively transfused patients, hypoperfusion and saline overdosing during resuscitation often induce acidosis. Acidosis alters coagulation through various pathways: platelets change their structure and shape and become spherical and deprived of their pseudopods at a pH below 7.4. Factor VII bonding to tissue factor is decreased, and the coagulation factors’ activity diminishes, resulting in lower thrombin generation, the main cause of co- agulopathic bleeding. Moreover, acidosis leads to increased fibrin degradation, further worsening the coagulopathy. Anemia contributes to coagulopathy because the red blood cells induce the marginalization of platelets by enabling their binding to the endothelium. Moreover, the red blood cells modulate the biochemical and functional responses within the activated platelets. They support the generation of thrombin through the exposure of membrane pro-coagulating phospholipids, stimulate the release of alpha granules, and the platelet production of cyclooxygenase.

Optimal massive bleeding management in major surgery involving pediatric patients requires a comprehensive knowledge of their hemostatic system and of the disruptions in the coagulation system during the specific surgical procedure. Early intervention is a must to avoid any coagulopathy-triggering factors such as hypothermia, acidosis, and hemodilution.

Adequate blood loss replacement is essential to reduce morbidity and mortality in pediatric surgical patients in situations where massive bleeding is expected. Complications of massive hemorrhage not only relate to the immediate concerns of hypovolemia but also the sequelae of incorrect replacement with crystalloids, colloids, and blood components. These sequelae include metabolic acidosis, dilutional coagulopathy, thrombocytopenia, hyperkalemia (from high potassium content of stored packed red blood cells), hypocalcemia (citrate toxicity), and hypothermia. Rapid administration of packed red blood cells with prolonged storage, particularly in the setting of hypovolemia, can result in hyperkalemic cardiac arrest.

The potassium concentration in a unit of packed red blood cells increases linearly with time. Blood irradiation drastically accelerates the transmembrane leakage of potassium from stored red blood cells. In an advisory statement, the Wake-up Safe group recommends using PRBCs less than 7 days from collection or packed red blood cells that have been washed and resuspended in saline to minimize the risk of hyperkalemia in scenarios where massive hemorrhage is anticipated[59]-[64]. Prevention and early treatment of complications from massive transfusion

Keep in mind the complications from blood transfusion, particularly the metabolic complications such as hypocalcemia, hyperkalemia, hypomagnesemia, metabolic acidosis and changes in the hemoglobin dissociation curve[65].

-

Coagulation monitoring

Goal-directed transfusion algorithms using point-of-care technology, such as viscoelastic testing (VET), are helpful to target specific hemostatic derangements and therefore guide transfusion of appropriate products in the appropriate quantities. Point of care viscoelastic testing allows the anesthesia team to track hemostatic derangements in real time guiding the point of care, goal directed management of coagulation and management the need for transfusion of the “yellow” blood components (fresh frozen plasma, cryoprecipitate and/ recombinant products such as fibrinogen concentrate or prothrombin). A VET-based transfusion algorithm should be considered for surgical procedures associated with a high risk of bleeding (e.g. liver transplant, neuro-craniofacial, spine, and cardiac surgeries) and in pediatric trauma.

Several guidelines favour use of viscoelastography (VET) and goal-directed viscoelastic haemostatic assay (VHA) testing using tailored transfusion algorithms for bleeding management in the perioperative period or in trauma. The 2022 ESAIC guidelines recommend utilising VHA-guided interventions to help guide transfusion in neonates and children undergoing cardiac and noncardiac surgery. VET such as thromboelastography (TEG®5000, TEG6s, Haemonetics Corporation, Braintree, MA, USA), thromboelatometry (Delta and Sigma ROTEM®, TEM Innovations GmbH, Munich, Germany), and Quantra Hemostasis Analyzer (Quantra®, HemoSonics, Durham, NC, USA) can analyse the dynamic viscoelastic properties of clot formation and fibrinolysis[66],[67].

-

How can we increase individual tolerance to anemia?

Traditionally the only parameter for blood transfusion had been the Hb level, currently the decision to transfuse or not Transfusion should not be based on Hb values but on the hemodynamic status, organ perfusion, oxygen extraction rate and clinical situation of the patient. We must always remember that the goal is to treat patients and not treat numbers. Restrictive

transfusion criteria that prioritize individualized based on gestational age, postnatal physiological indicators over hemoglobin levels alone. RBC transfusion should be age, oxygen dependency, respiratory support hemodynamic status, and comorbidities. In hemodynamically stable patients with hemoglobin above 7.0 g/dL, transfusion is generally discouraged, while a target of 7 to 9 g/dL is recommended during active bleeding[68]. Higher thresholds may be necessary for neonates, critically ill children with high oxygen requirements, cyanotic congenital heart disease, and preexisting hemoglob-inopathy, with transfusion decisions incorporating markers of end-organ perfusion (e.g., lactate or base deficit)[69].

The first goal of RBC transfusion is to increase the transport and delivery of oxygen to the tissues and this goal can be achieved with lower levels of Hb than those traditionally used without having an increase in morbidity and mortality.

Adherence to restrictive transfusion with a low transfusion threshold is one of the most cost-effective tools to reduce the number of unnecessary transfusions. Different studies have reported that this simple strategy has reduced the incidence of transfusions by 40%. Lacroix and colleagues published a landmark multicenter randomized control trial in pediatric intensive care patients (TRIPICU) that compared a restrictive (Hb < 7.0 g/dL) versus a liberal (Hb < 9.5 g/dL) transfusion strategy in critically ill children with the primary outcome designated as new or progressive multiorgan failure. This trial demonstrated that the restrictive transfusion strategy was as safe as the liberal transfusion strategy but reduced RBC transfusions by half in the restrictive transfusion group[70]-[72].

It must be remembered that a restrictive transfusion threshold be maintained throughout the perioperative journey. For a haemodynamically stable patient there is no evidence that transfusion is of benefit unless the haemoglobin is less than 7 g/dl.

So when should we transfuse? In a stable child, without major comorbidity or ongoing blood loss, a threshold of 7 g/dl should be used. This restrictive transfusion practice has no association with an increase in adverse outcomes and is associated with reduced blood use. Decisions to transfuse should also anticipate any further drop in haemoglobin, especially if frequent monitoring is not possible.

During active blood loss it is useful to calculate the point at which blood transfusion is required. This includes an appreciation of how blood volume varies with age: a neonate has a circulating volume of 90 ml/kg, an infant 75-80 ml/kg and a child 70-75 ml/kg. This allows a calculation to be made of the volume at which a patient has lost a certain percentage of their circulating volume and to appreciate how small volumes that may mean a significant blood loss[5].

The Pediatric Critical Care Transfusion and Anemia eXpertise Initiative (TAXI) guidelines and the European Society of Anaesthesia and Intensive Care guidelines recommend against transfusion if the child is haemodynamically stable with an Hb concentration of at least 7 g/dl. Once transfusion is initiated, recommendations are to avoid over-transfusion, with a post-transfusion Hb target of 9.5 g/dl in the haemodynamically stable child without active bleeding. High-risk groups, such as cyanotic children or neonates, might require higher threshold.

Physiological optimisation together with RBC mass optimisation is the best strategy to guide the decision to transfuse or to withhold transfusion in paediatric patients . Tolerance of anaemia is likely based more on tissue oxygen delivery, end organ perfusion, oxygen extraction, and compensatory physiology than a single Hb concentration. Emerging literature suggests that novel technologies, such as cerebral and somatic near infrared spectroscopy (NIRS), can better quantify and monitor oxygen consumption and delivery, especially when taken together with patient haemodynamic and laboratory markers indicative of sufficient perfusion (e.g. lactate, base deficit, ph).

A restrictive transfusion strategy also applies to management of coagulopathic haemostatic abnormalities. Platelet and plasma transfusions are commonly administered in paediatric clinical care settings, when clinically significant bleeding is present or expected, or to prevent bleeding complication.

-

Postoperative blood management

Post operative blood conservation measures include using small-volume phlebotomy tubes, point-of-care devices, closed sampling systems, and eliminating ‘‘standing daily” laboratory orders. Next to minimizing loss, adapting restrictive thresholds would be very effective in minimizing transfusion without increasing adverse events. Reduced sampling has shown to be more cost-efficient and no significant difference was shown in adverse outcomes (eg, extubation failure, hospital mortality, and central-catheter-associated infection). Reduced postoperative blood sampling is particularly relevant to patients undergoing minor procedures in Low and Middle income countries where laboratory resources could be directed as per clinical need. Other supportive postoperative measures of patient blood management include wound site observations, use of pressure dressings, and reduced dressing changes, where clinically appropriate.

-

Development of facility-specific transfusion practice guidelines

The first step in implementing a blood utilization review program is to establish a set of institution specific, evidence-based transfusion practice guidelines for each blood component, including component modifications such as irradiation where appropriate. Additionally, separate guidelines may be developed for specific patient populations such as neonates and pediatrics, patients requiring massive transfusion, cardiothoracic surgery patients, liver transplant surgery or patients with sickle cell disease.

Implementation of clinical guidelines to promote education among the physicians is an essential, but insufficient, measure to guarantee its correct use. The requests audit is an important tool to assess the implementation of these protocols. A post-transfusion, retrospective audit can provide information for further education of the clinical staff, but does not prevent the occurrence of inadequate transfusion. A pre-transfusion, concurrent audit is effective in preventing the unwanted blood transfusion, but is a laborious and time-consuming task. The development of Clinical Decision Support (CDS) systems, in which the clinical guidelines are associated with the electronic prescription software may help in alerting the prescribing physician, based on the available laboratory results, radiology tests and clinical information, to verify if the requested transfusion is compliant with the best practices or should be reviewed. This approach avoids unnecessary use of blood components, promoting a decrease of up to 20% in the volume of red blood cells (RBCs) transfused.

In addition to the possible financial impact, the program could promote more availability of blood, where and when it is needed. The promoting of blood availability is of great importance because an aging population and decreasing number of blood donor candidates generate a dangerous imbalance between the transfusion needs and blood inventory. Starting a PBM program can be a daunting task that requires support from hospital administration, information technology (IT) teams, medical and nursing staff, and the transfusion service.

-

Novel techniques in PBM

Artificial intelligence (AI) and Machine Learning (ML) use sophisticated algorithms to ‘learn’ and ‘self-correct’ by assimilating and distilling large amounts of data, which can then be used to assist or optimize transfusion practices. The applications of novel techniques like AI/ML are still limited but increasingly being explored for data-driven inventory management decisions for blood products including demand forecasting and inventory optimization. From the PBM side, the main application can be for more effective and efficient care delivery by predicting disease trajectory and the need for an intervention like RBC transfusion in massively bleeding or trauma patients or sick patients in the Intensive Care Units[73].

-

Conclusions

Historically, allogeneic blood transfusion has become one of the most common medical practices worldwide, largely due to its development and widespread use during the World Wars. Unfortunately, it has been prescribed without the proper scrutiny by physicians, supposedly triggered by the low prevalence and severity of transfusion reactions, especially those of greater severity, suggesting it is a safe therapeutic resource. However, the advancement of molecular scientific methods has identified increasingly deleterious effects of blood transfusions on the recipients, leading to increased morbidity and mortality. The immunomodulation related to allogeneic blood transfusion (transfusion-related immunomodulation) brings significant consequences; these mechanisms have been associated with the diminished function of natural killer cells and antigen-presenting cells, a reduction in cell-mediated immunity, and an increase in regulatory T cells. Through these immunomodulatory and inflammatory effects, allogeneic blood transfusions have been associated with a higher risk of infection, prolonged hospital stays, and increased morbidity and mortality, regardless of the presence of confounding factors, such as demographic characteristics, healthcare team, hospital infrastructure, and patient conditions.

Blood transfusion in pediatrics is not about the transfusion of smaller volumes to smaller humans because children are not simply smaller adults due to the physiologically higher average haemoglobin concentrations and oxygen requirements compared to adults.

A comprehensive understanding of pathophysiology of hematologic derangements and a multimodal patient blood management strategy is crucial in quickly and safely managing anemia and coagulopathy associated with massive intraoperative blood loss during pediatric major surgery. The goals should be to maintain hemodynamic stability, oxygen carrying capacity and perfusion to vital organs. Overtransfusion and transfusion-related side-effects should be minimized. Future efforts should focus on furthering the education of pediatric anesthesiologists, surgeons and intensivists regarding pediatric patient blood management techniques with particular focus on goal-directed targeted diagnosis using point-of-care testing and targeted therapy.

Adherence to transfusion guidelines should be an institutional priority at every hospital. Widespread compliance with guidelines will result in increased safety as well as cost savings for patients, payers, and medical centers, as well as preservation of the blood supply for patients who truly need transfusions.

Every hospital must develop a multidisciplinary protocol to treat pediatric massive bleeding in accordance with the resources available at the institution and the needs of the community. Specialist who takes care of children with severe bleeding must anticipate coagulopathy and focus on achieving hemostasis as soon as possible; early intervention is in order for the multiple aspects of hemorrhagic shock such as hypothermia, acidosis, and hemodilution.

It is well known that implementation of practice improvements requires drivers to actively engage stakeholders, change behavior and culture, make infrastructure alterations to the delivery of health care services, and support patient-specific plans of care. These roles are essential and can be attributed to the “human component” of implementation of Patient Blood Manament. Current scientific evidence supports the effectiveness of PBM by reducing the need for blood transfusions, decreasing associated complications and mortality, and promoting more efficient and safer PBM. Thus, PBM not only improves clinical outcomes for patients but also contributes to the economic sustainability of healthcare systems. The implementation of this program may lead to optimized medical practices, yielding benefits for both patients and healthcare systems. Therefore, based on current evidence, the implementation and dissemination of PBM in hospitals and healthcare centers is strongly recommended[74],[75].

-

References

1. Harrison E, Bolton P. Serious hazards of transfusion in children (SHOT). Pediatr Anesth. enero de 2011;21(1):10-3.

2. Inghilleri G. Prediction of transfusion requirements in surgical patients: a review. Transfus Altern Transfus Med. marzo de 2010;11(1):10-9. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1778-428X.2009.01118.x.

3. Sullivan HC, Roback JD. The pillars of patient blood management: key to successful implementation (Article, p. 2840). Transfusion (Paris). septiembre de 2019;59(9):2763-7.

4. Zacharowski K, Spahn DR. Patient blood management equals patient safety. Best Pract Res Clin Anaesthesiol. junio de 2016;30(2):159-69. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bpa.2016.04.008.

5. Goobie SM, Gallagher T, Gross I, Shander A. Society for the advancement of blood management administrative and clinical standards for patient blood management programs. 4th edition (pediatric version). Veyckemans F, editor. Pediatr Anesth. marzo de 2019;29(3):231-6.

6. Kumba C. Patient Blood Management in Craniosynostosis Surgery. Open J Mod Neurosurg. 2021;11(04):211–22. https://doi.org/10.4236/ojmn.2021.114025.

7. Beethe AB, Spitznagel RA, Kugler JA, Goeller JK, Franzen MH, Hamlin RJ, et al. The Road to Transfusion-free Craniosynostosis Repair in Children Less Than 24 Months Old: A Quality Improvement Initiative. Pediatr Qual Saf. julio de 2020;5(4):e331.

8. Karacaer F. Patient Blood Management in Pediatric Cardiac Surgery. Cukurova Anestezi Ve Cerrahi Bilim Derg. 19 de marzo de 2025;8(1):12-8. https://doi.org/10.36516/jocass.1591406.

9. Tan GM, Murto K, Downey LA, Wilder MS, Goobie SM. Error traps in Pediatric Patient Blood Management in the Perioperative Period. Pediatr Anesth. agosto de 2023;33(8):609-19. https://doi.org/10.1111/pan.14683.

10. Guzzetta NA, Miller BE. Principles of hemostasis in children: models and maturation. Pediatr Anesth. enero de 2011;21(1):3-9. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1460-9592.2010.03410.x.

11. Hofmann A, Shander A, Blumberg N, Hamdorf JM, Isbister JP, Gross I. Patient Blood Management: Improving Outcomes for Millions While Saving Billions. What Is Holding It Up? Anesth Analg. septiembre de 2022;135(3):511-23.

12. Meyer HM, Torborg A, Cronje L, Thomas J, Bhettay A, Diedericks J, et al. The association between preoperative anemia and postoperative morbidity in pediatric surgical patients: A secondary analysis of a prospective observational cohort study. Goobie S, editor. Pediatr Anesth. julio de 2020;30(7):759-65. https://doi.org/10.1111/pan.13872.

13. McCormack G, Faraoni D, DiNardo JA, Goobie SM. Association between preoperative anaemia, transfusion, and outcomes in children undergoing noncardiac surgery. Br J Anaesth. agosto de 2025;135(2):375-81. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bja.2025.04.050.

14. Shander A, Corwin HL, Meier J, Auerbach M, Bisbe E, Blitz J, et al. Recommendations From the International Consensus Conference on Anemia Management in Surgical Patients (ICCAMS). Ann Surg. abril de 2023;277(4):581-90.

15. Faraoni D, DiNardo JA, Goobie SM. Relationship Between Preoperative Anemia and In-Hospital Mortality in Children Undergoing Noncardiac Surgery. Anesth Analg. diciembre de 2016;123(6):1582-7. https://doi.org/10.1213/ANE.0000000000001499.

16. Goobie SM, Faraoni D, Zurakowski D, DiNardo JA. Association of Preoperative Anemia With Postoperative Mortality in Neonates. JAMA Pediatr. 1 de septiembre de 2016;170(9):855. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2016.1032.

17. Chumble A, Brush P, Muzaffar A, Tanaka T. The Effects of Preoperative Administration of Erythropoietin in Pediatric Patients Undergoing Cranial Vault Remodeling for Craniosynostosis. J Craniofac Surg. julio de 2022;33(5):1424-7.

18. Coombs DM, Knackstedt R, Patel N. Optimizing Blood Loss and Management in Craniosynostosis Surgery: A Systematic Review of Outcomes Over the Last 40 Years. Cleft Palate Craniofacial J. diciembre de 2023;60(12):1632-44.

19. Patient blood management guidelines. Module 6. Neonatal and paediatrics. Canberra (ACT): National Blood Authority; 2016.

20. The Urgent Need to Implement Patient Blood Management. Policy Brief. 1st ed. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2021. 1 pp.

21. Safiri S, Kolahi AA, Noori M, Nejadghaderi SA, Karamzad N, Bragazzi NL, et al. Burden of anemia and its underlying causes in 204 countries and territories, 1990–2019: results from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. J Hematol OncolJ Hematol Oncol [Internet]. 4 de noviembre de 2021 [citado 9 de julio de 2025];14(1). Disponible en: https://jhoonline.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s13045-021-01202-2

22. East P, Delker E, Lozoff B, Delva J, Castillo M, Gahagan S. Associations Among Infant Iron Deficiency, Childhood Emotion and Attention Regulation, and Adolescent Problem Behaviors. Child Dev. marzo de 2018;89(2):593-608.

23. Shander A, Hardy JF, Ozawa S, Farmer SL, Hofmann A, Frank SM, et al. A Global Definition of Patient Blood Management. Anesth Analg. septiembre de 2022;135(3):476-88. https://doi.org/10.1213/ANE.0000000000005873.

24. Goobie SM. Patient Blood Management Is a New Standard of Care to Optimize Blood Health. Anesth Analg. septiembre de 2022;135(3):443-6. https://doi.org/10.1213/ANE.0000000000006168.

25. Bhananker SM, Ramamoorthy C, Geiduschek JM, Posner KL, Domino KB, Haberkern CM, et al. Anesthesia-Related Cardiac Arrest in Children: Update from the Pediatric Perioperative Cardiac Arrest Registry. Anesth Analg. agosto de 2007;105(2):344-50.

26. Zuluaga Giraldo M. Sangrado perioperatorio en niños. Aspectos básicos. Rev Colomb Anestesiol. enero de 2013;41(1):44-9.

27. Zuluaga Giraldo M. Management of perioperative bleeding in children. Step by step review. Colomb J Anesthesiol. enero de 2013;41(1):50-6.

28. Manual de anestesiología pediátrica. 1a edición, noviembre 2015; 1a reimpresión digital, junio 2018. Madrid, España: Editorial Médica Panamericana; 2018.

29. Achey MA, Nag UP, Robinson VL, Reed CR, Arepally GM, Levy JH, et al. The Developing Balance of Thrombosis and Hemorrhage in Pediatric Surgery: Clinical Implications of Age-Related Changes in Hemostasis. Clin Appl Thromb [Internet]. 1 de enero de 2020 [citado 9 de julio de 2025];26. Disponible en: https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/1076029620929092

30. Erdoes G, Faraoni D, Koster A, Steiner ME, Ghadimi K, Levy JH. Perioperative Considerations in Management of the Severely Bleeding Coagulopathic Patient. Anesthesiology. mayo de 2023;138(5):535-60. https://doi.org/10.1097/ALN.0000000000004520.

31. Yamada C, Edelson MF, Lee AC, Saifee NH, Dinov ID. Transfusion‐associated hyperkalemia in pediatric population: Analyses for risk factors and recommendations. Transfusion (Paris). diciembre de 2022;62(12):2503-14.

32. Zuluaga Giraldo M. Management of perioperative bleeding in children. Step by step review. Colomb J Anesthesiol. enero de 2013;41(1):50-6.

33. Burke M, Sinha P, Luban NL, Posnack NG. Transfusion-Associated Hyperkalemic Cardiac Arrest in Neonatal, Infant, and Pediatric Patients. Front Pediatr [Internet]. 29 de octubre de 2021 [citado 9 de julio de 2025];9. Disponible en: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fped.2021.765306/full

34. Shander A, Brown J, Licker M, Mazer DC, Meier J, Ozawa S, et al. Standards and Best Practice for Acute Normovolemic Hemodilution: Evidence-based Consensus Recommendations. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. julio de 2020;34(7):1755-60.

35. Crescini WM, Muralidaran A, Shen I, LeBlanc A, You J, Giacomuzzi C, et al. The use of acute normovolemic hemodilution in paediatric cardiac surgery. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. julio de 2018;62(6):756-64. https://doi.org/10.1111/aas.13095.

36. Perini FV, Montano-Pedroso JC, Oliveira LC, Donizetti E, Rodrigues RDR, Rizzo SRCP, et al. Consensus of the Brazilian association of hematology, hemotherapy and cellular therapy on patient blood management. Hematol Transfus Cell Ther. abril de 2024;46:S48-52. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.htct.2024.02.019.

37. Longacre MM, Seshadri SC, Adil E, Baird LC, Goobie SM. Perioperative management of pediatric patients undergoing juvenile angiofibroma resection. A case series and educational review highlighting patient blood management. Pediatr Anesth. julio de 2023;33(7):510-9.

38. Faraoni D, Meier J, New HV, Van Der Linden PJ, Hunt BJ. Patient Blood Management for Neonates and Children Undergoing Cardiac Surgery: 2019 NATA Guidelines. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. diciembre de 2019;33(12):3249-63.

39. Klein AA, Bailey CR, Charlton AJ, Evans E, Guckian‐Fisher M, McCrossan R, et al. Association of Anaesthetists guidelines: cell salvage for peri‐operative blood conservation 2018. Anaesthesia. septiembre de 2018;73(9):1141-50.

40. Lecker I, Wang D, Whissell PD, Avramescu S, Mazer CD, Orser BA. Tranexamic acid–associated seizures: Causes and treatment. Ann Neurol. enero de 2016;79(1):18-26.

41. Varidel AD, Meara JG, Proctor MR, Goobie SM. Antifibrinolytics as a Patient Blood Management Modality in Craniosynostosis Surgery: Current Concepts and a View to the Future. Curr Anesthesiol Rep. 24 de junio de 2023;13(3):148-58.

42. King MR, Staffa SJ, Stricker PA, Pérez‐Pradilla C, Nelson O, Benzon HA, et al. Safety of antifibrinolytics in 6583 pediatric patients having craniosynostosis surgery: A decade of data reported from the multicenter Pediatric Craniofacial Collaborative Group. Pediatr Anesth. diciembre de 2022;32(12):1339-46. https://doi.org/10.1111/pan.14540.

43. Goobie SM, Staffa SJ, Meara JG, Proctor MR, Tumolo M, Cangemi G, et al. High-dose versus low-dose tranexamic acid for paediatric craniosynostosis surgery: a double-blind randomised controlled non-inferiority trial. Br J Anaesth. septiembre de 2020;125(3):336-45. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bja.2020.05.054.

44. Goobie SM, Zurakowski D, Glotzbecker MP, McCann ME, Hedequist D, Brustowicz RM, et al. Tranexamic Acid Is Efficacious at Decreasing the Rate of Blood Loss in Adolescent Scoliosis Surgery: A Randomized Placebo-Controlled Trial. J Bone Jt Surg. 5 de diciembre de 2018;100(23):2024-32.

45. Goobie SM, Faraoni D. Tranexamic acid and perioperative bleeding in children: what do we still need to know? Curr Opin Anaesthesiol. junio de 2019;32(3):343-52. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACO.0000000000000728.

46. Goobie SM, Cladis FP, Glover CD, Huang H, Reddy SK, Fernandez AM, et al. Safety of antifibrinolytics in cranial vault reconstructive surgery: a report from the pediatric craniofacial collaborative group. Anderson B, editor. Pediatr Anesth. marzo de 2017;27(3):271-81. https://doi.org/10.1111/pan.13076.

47. Wang JT, Seshadri SC, Butler CG, Staffa SJ, Kordun AS, Lukovits KE, et al. Tranexamic Acid Use in Pediatric Craniotomies at a Large Tertiary Care Pediatric Hospital: A Five Year Retrospective Study. J Clin Med. 30 de junio de 2023;12(13):4403.

48. Fenger-Eriksen C, D’Amore Lindholm A, Nørholt SE, Von Oettingen G, Tarpgaard M, Krogh L, et al. Reduced perioperative blood loss in children undergoing craniosynostosis surgery using prolonged tranexamic acid infusion: a randomised trial. Br J Anaesth. junio de 2019;122(6):760-6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bja.2019.02.017.

49. Patel PA, Wyrobek JA, Butwick AJ, Pivalizza EG, Hare GMT, Mazer CD, et al. Update on Applications and Limitations of Perioperative Tranexamic Acid. Anesth Analg. septiembre de 2022;135(3):460-73. https://doi.org/10.1213/ANE.0000000000006039.

50. Lavoie J. Blood transfusion risks and alternative strategies in pediatric patients. Pediatr Anesth. enero de 2011;21(1):14-24. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1460-9592.2010.03470.x.

51. Kietaibl S, Ahmed A, Afshari A, Albaladejo P, Aldecoa C, Barauskas G, et al. Management of severe peri-operative bleeding: Guidelines from the European Society of Anaesthesiology and Intensive Care: Second update 2022. Eur J Anaesthesiol. abril de 2023;40(4):226-304.

52. Erdoes G, Goobie SM, Haas T, Koster A, Levy JH, Steiner ME. Perioperative considerations in the paediatric patient with congenital and acquired coagulopathy. BJA Open. diciembre de 2024;12:100310. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bjao.2024.100310.

53. Wittenmeier E, Piekarski F, Steinbicker AU. Blood product transfusions for children in the perioperative period and for critically ill children. Dtsch Ärztebl Int [Internet]. 26 de enero de 2024 [citado 9 de julio de 2025]; Disponible en: https://www.aerzteblatt.de/10.3238/arztebl.m2023.0243 https://doi.org/10.3238/arztebl.m2023.0243.

54. Mo YD, Delaney M. Transfusion in Pediatric Patients. Clin Lab Med. marzo de 2021;41(1):1-14. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cll.2020.10.001.

55. Munlemvo DM, Tobias JD, Chenault KM, Naguib A. Prothrombin Complex Concentrates to Treat Coagulation Disturbances: An Overview With a Focus on Use in Infants and Children. Cardiol Res. febrero de 2022;13(1):18-26.

56. Valentine SL, Cholette JM, Goobie SM. Transfusion Strategies for Hemostatic Blood Products in Critically Ill Children: A Narrative Review and Update on Expert Consensus Guidelines. Anesth Analg. septiembre de 2022;135(3):545-57. https://doi.org/10.1213/ANE.0000000000006149.

57. Maw G, Furyk C. Pediatric Massive Transfusion: A Systematic Review. Pediatr Emerg Care. agosto de 2018;34(8):594-8. https://doi.org/10.1097/PEC.0000000000001570.

58. Bolliger D, Görlinger K, Tanaka KA, Warner DS. Pathophysiology and Treatment of Coagulopathy in Massive Hemorrhage and Hemodilution. Anesthesiology. 1 de noviembre de 2010;113(5):1205-19. https://doi.org/10.1097/ALN.0b013e3181f22b5a.

59. Pötzsch B, Ivaskevicius V. Haemostasis management of massive bleeding. Hämostaseologie. 2011 Feb;31(1):15–20. https://doi.org/10.5482/ha-1148 PMID:21311819

60. Lee AC, Reduque LL, Luban NLC, Ness PM, Anton B, Heitmiller ES. Transfusion‐associated hyperkalemic cardiac arrest in pediatric patients receiving massive transfusion. Transfusion (Paris). enero de 2014;54(1):244-54. https://doi.org/10.1111/trf.12192.

61. Sesok‐Pizzini D, Pizzini M. Hyperkalemic cardiac arrest in pediatric patients undergoing massive transfusion: unplanned emergencies. Transfusion (Paris). enero de 2014;54(1):4-7. https://doi.org/10.1111/trf.12470.

62. Bhananker SM, Ramamoorthy C, Geiduschek JM, Posner KL, Domino KB, Haberkern CM, et al. Anesthesia-Related Cardiac Arrest in Children: Update from the Pediatric Perioperative Cardiac Arrest Registry. Anesth Analg. agosto de 2007;105(2):344-50.

63. Strauss RG. Red blood cell storage and avoiding hyperkalemia from transfusions to neonates and infants. Transfusion (Paris). septiembre de 2010;50(9):1862-5. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1537-2995.2010.02789.x.

64. Thomas D, Wee M, Clyburn P, Walker I, Brohi K, Collins P, et al. Blood transfusion and the anaesthetist: management of massive haemorrhage. Anaesthesia. noviembre de 2010;65(11):1153-61. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2044.2010.06538.x.

65. Vlatten A. Pediatric massive hemorrhage—are we all following similar protocols? Can J Anesth Can Anesth. abril de 2024;71(4):443-6.

66. Haas T, Goobie S, Spielmann N, Weiss M, Schmugge M. Improvements in patient blood management for pediatric craniosynostosis surgery using a ROTEM®‐assisted strategy – feasibility and costs. Davidson A, editor. Pediatr Anesth. julio de 2014;24(7):774-80.

67. Haas T, Faraoni D. Viscoelastic testing in pediatric patients. Transfusion (Paris) [Internet]. octubre de 2020 [citado 9 de julio de 2025];60(S6). Disponible en: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/trf.16076 https://doi.org/10.1111/trf.16076.

68. Carson JL, Stanworth SJ, Guyatt G, Valentine S, Dennis J, Bakhtary S, et al. Red Blood Cell Transfusion: 2023 AABB International Guidelines. JAMA. 21 de noviembre de 2023;330(19):1892.

69. Downey LA, Goobie SM. Perioperative Pediatric Erythrocyte Transfusions: Incorporating Hemoglobin Thresholds and Physiologic Parameters in Decision-making. Anesthesiology. noviembre de 2022;137(5):604-19.

70. Goobie SM. A blood transfusion can save a child’s life or threaten it. Pediatr Anesth. diciembre de 2015;25(12):1182-3. https://doi.org/10.1111/pan.12816.

71. Lacroix J, Hébert PC, Hutchison JS, Hume HA, Tucci M, Ducruet T, et al. Transfusion Strategies for Patients in Pediatric Intensive Care Units. N Engl J Med. 19 de abril de 2007;356(16):1609-19.

72. Doctor A, Cholette JM, Remy KE, Argent A, Carson JL, Valentine SL, et al. Recommendations on RBC Transfusion in General Critically Ill Children Based on Hemoglobin and/or Physiologic Thresholds From the Pediatric Critical Care Transfusion and Anemia Expertise Initiative. Pediatr Crit Care Med. septiembre de 2018;19(9S):S98-113.

73. Al-Mozain N, Arora S, Goel R, Pavenski K, So-Osman C. Patient blood management in adults and children: What have we achieved, and what still needs to be addressed? Transfus Clin Biol. agosto de 2023;30(3):355-9.