Gianpaolo Cecioni1*, Taher Touré2

Recibido: 01-08-2025

Aceptado: 14-09-2025

©2025 El(los) Autor(es) – Esta publicación es Órgano oficial de la Sociedad de Anestesiología de Chile

Revista Chilena de Anestesia Vol. 54 Núm. 5 pp. 770-773|https://doi.org/10.25237/revchilanestv54n5-42

PDF|ePub|RIS

Manejo anestésico de un neonato con un tumor intrepericárdico

Abstract

Anterior mediastinal masses in neonates present a significant anesthetic challenge due to the risk of airway and cardiovascular compromise. Primary cardiac tumors, though rare, require meticulous planning for safe perioperative management. We describe the case of a 4-day-old neonate with an intrapericardial mass compressing the left ventricle and coronary artery, successfully resected under cardiopulmonary bypass with a tailored anesthetic approach emphasizing airway safety, hemodynamic stability, and proactive arrhythmia management.

Resumen

Las masas mediastínicas anteriores en neonatos presentan un desafío anestésico significativo debido al riesgo de compromiso de las vías respiratorias y cardiovascular. Los tumores cardíacos primarios, aunque raros, requieren una planificación meticulosa para un manejo perioperatorio seguro. Describimos el caso de un neonato de 4 días de edad con una masa intrapericárdica que comprimía el ventrículo izquierdo y la arteria coronaria, resecada con éxito bajo circulación extracorpórea con un enfoque anestésico personalizado que enfatizaba la seguridad de las vías respiratorias, la estabilidad hemodinámica y el manejo proactivo de arritmias.

-

Introduction

Primary cardiac tumors are rare entities with an autopsy frequency of 0,001% to 0,030%, and three-quarters of these tumors are benign[1]. They are associated with high anesthetic risk due to their potential to compromise airway patency, vascular flow, and cardiac output, either independently or in combination[2]. These risks are magnified when the mass is intrapericardial and intimately related to critical structures such as the heart and great vessels. The anesthetic management of such patients is particularly complex, owing to the narrow physiological margin in neonates. This report presents the perioperative strategy used in a 4-day-old neonate undergoing resection of an intrapericardial cardiac tumor, with a focus on preserving spontaneous ventilation, minimizing hemodynamic fluctuations, and addressing potential arrhythmogenic complications.

-

Case presentation

A 4-day-old full-term female neonate (gestational age 37+6 weeks, birth weight 3,062 g) was referred for evaluation following prenatal detection of a homogeneous cardiac mass. Delivery was vaginal, induced, and uneventful. APGAR scores were 8-9-9. Prostaglandin E1 infusion was initiated at birth. By the second day of life, the patient developed respiratory distress with differential oxygen saturation (90% pre-ductal vs 50% post-ductal), raising concern for ductal-dependent perfusion and pulmonary hypertension, which can be one of the earliest and most common cardiac manifestations[1]. Bilevel positive airway pressure (BPAP) was initiated.

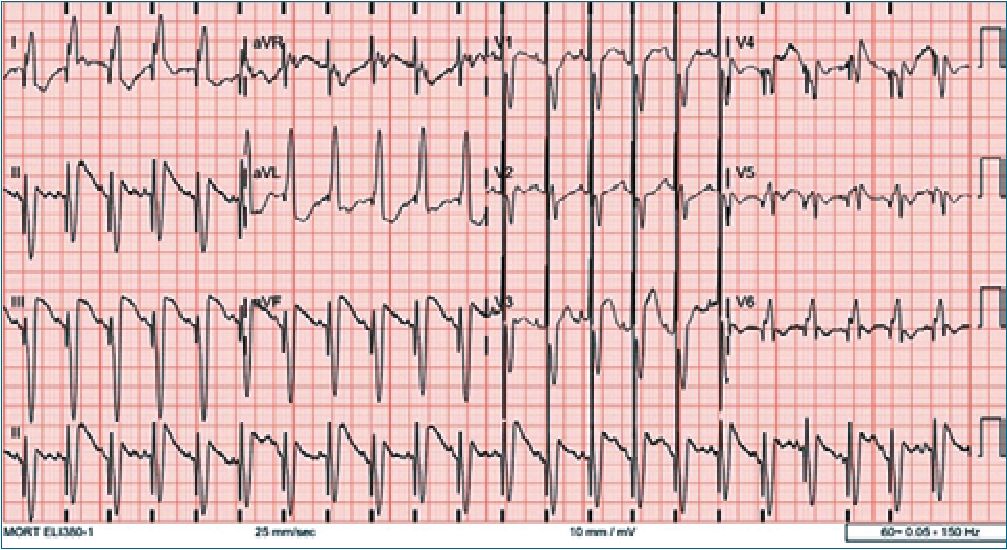

Transthoracic echocardiography, later confirmed by computed tomography imaging (Figure 1), revealed a 3.0 x 3.3 cm anterior intrapericardial mass compressing the left ventricle, displacing the heart rightward (dextroposition), and obscuring the left coronary artery. There was no evidence of outflow tract obstruction. Additional findings included a patent foramen ovale with left-to-right shunting, a 2.5 mm patent ductus arteriosus (PDA) with bidirectional shunting, and a mild pericardial effusion. Electrocardiography showed complete left bundle branch block, ST-segment elevation, T wave inversion, and a spike at the onset of the QRS complex, all suggestive of myocardial involvement (Figure 2). Laboratory investigations were unremarkable. Surgical resection was indicated by the cardiac surgery team.

The patient was admitted to the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) for stabilization and monitoring, including non-invasive blood pressure (NIBP), oxygen saturation, and an umbilical central line. She remained on BPAP until transfer to the operating room.

Figure 1. Axial, sagittal, and coronal CT images demonstrating a large, well-circumscribed intrapericardial mass compressing the left ventricle and displacing the heart rightward (dextroposition). No airway obstruction was noted, but significant distortion of cardiac anatomy is evident.

Figure 2. Initial electrocardiogram showing complete left bundle branch block, ST-segment elevation, T wave inversion, and a prominent QRS spike-findings suggestive of myocardial irritation or infiltration by the tumor.

Oral intubation with a 3.0 mm microcuff endotracheal tube was successful. A previous attempt at nasal intubation had failed, likely due to congenital choanal atresia. No adverse changes in ventilation or circulation occurred during airway instrumentation.

Anesthesia was maintained with infusions of midazolam, ketamine, and dexmedetomidine to ensure deep sedation and hemodynamic stability while avoiding myocardial depression. Central venous access was obtained via ultrasound-guided insertion of a 4F, 5 cm double-lumen catheter into the right internal jugular vein. A transesophageal echocardiography (TEE) probe was placed for real-time intraoperative cardiac assessment.

Surgical resection was performed under cardiopulmonary bypass (CPB). Total CPB duration was 76 minutes, with an aortic cross-clamp time of 44 minutes. During separation from CPB, the patient required a combination of vasoactive agents: adrenaline (0.08 mcg/kg/min), vasopressin (0.6 mIU/kg/min), and noradrenaline (0.01 mcg/kg/min) to support myocardial function.

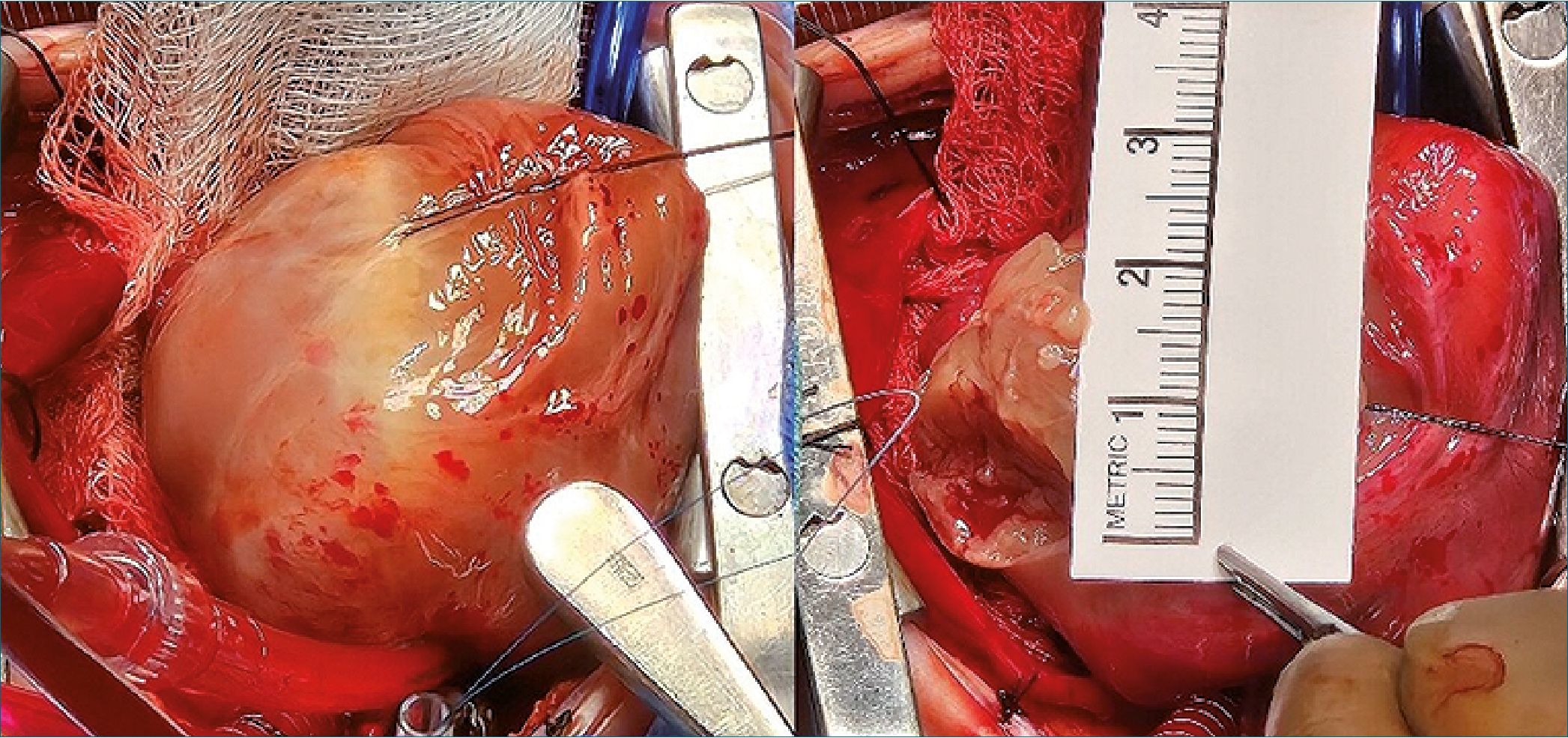

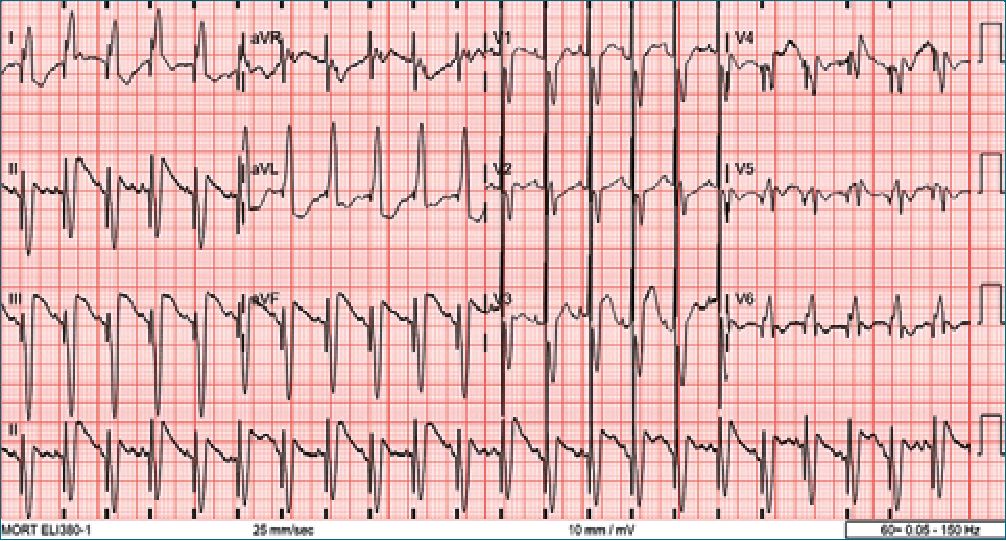

TEE post-bypass revealed lateral wall hypokinesis of the left ventricle and moderate mitral regurgitation. A transient 2:1 atrioventricular block was noted, followed by reversion to sinus rhythm, although the complete left bundle branch block persisted (Figure 3 and 4).

-

Intraoperative management

Upon arrival in the operating room, standard monitoring was established, including non-invasive blood pressure, five- lead electrocardiography, and dual pulse oximetry placed on the upper and lower limbs to detect ductal-dependent perfusion discrepancies. Anticipating the risk of hemodynamic or respiratory collapse during induction, a strategy centered on preserving spontaneous ventilation was adopted.

Induction was carried out with intravenous ketamine and incremental doses of sufentanil, providing adequate analgesia while maintaining respiratory drive. Manual ventilation was supported by an inhalation therapist using the anesthesia circuit. Hemodynamic parameters remained stable throughout.

A left radial arterial line was successfully inserted under ultrasound guidance while the patient continued to breathe spontaneously. A 24G peripheral intravenous catheter was secured in the right saphenous vein. Following confirmation of vascular access and clinical stability, rocuronium was administered for neuromuscular relaxation. Sugammadex was prepared for immediate use in the event of respiratory compromise.

-

Postoperative course

The patient was transferred intubated to the pediatric intensive care unit (PICU) with stable hemodynamics. Vasoactive agents were continued and gradually tapered over the first postoperative days. Atrial arrhythmia developed and were treated effectively with procainamide. Serial echocardiograms demonstrated progressive improvement in left ventricular function. One month postoperatively, the ejection fraction had normalized, improving from 30.8% to 69%.

Figure 3. Intraoperative image showing the large fibroma after pericardiotomy. The tumor was closely adherent to the epicardial surface of the left ventricle and in proximity to the coronary vasculature. A surgical ruler confirms a maximal diameter of approximately 3.5 cm.

Figure 4. Follow-up ECG after surgical resection showing persistence of complete left bundle branch block but resolution of the transient 2:1 atrioventricular block.

-

Discussion

Primary cardiac tumors in neonates are exceedingly rare, with fibromas representing approximately 20% of such lesions[2]. Despite their benign histology, these tumors may cause significant clinical deterioration depending on their size, location, and impact on adjacent cardiovascular structures[3].

Anesthetic management must be highly individualized in these patients, especially when intrapericardial masses pose a threat to hemodynamic or airway stability[2],[4]. In our case, although the patient’s imaging did not demonstrate airway compression, the presence of an intrapericardial mass in close proximity to the tracheobronchial tree and the need for BPAP prior to surgery, raised concern for dynamic airway collapse during induction, particularly with loss of diaphragmatic tone and changes in thoracic mechanics. In cases where airway patency remains uncertain or symptoms suggest positional compromise, alternative induction strategies should be considered. These include maintaining spontaneous ventilation, inducing in the lateral or prone position to reduce mass effect, and having rigid bronchoscopy and surgical airway equipment immediately available.

Maintaining spontaneous ventilation during induction is widely recommended in cases of mediastinal or intrapericardial mass to avoid catastrophic airway or cardiovascular collapse[5]. Ketamine was chosen as the primary induction agent due to its sympathomimetic properties, which support systemic vascular resistance and myocardial contractility, while also preserving spontaneous ventilation[6].

Sufentanil was administered in incremental doses to provide analgesia while minimizing the risk of bradycardia, apnea, or hypotension associated with bolus administration of potent opioids in neonates. The use of propofol or volatile agents was intentionally avoided due to their depressant effects on myocardial contractility and systemic vascular resistance, which could exacerbate hypotension during induction, particularly in patients with impaired preload or compromised coronary perfusion[7],[8].

Maintenance was achieved with a balanced infusion regimen including midazolam, ketamine, and dexmedetomidine. The addition of dexmedetomidine provided sympatholytic and anxiolytic effects while preserving spontaneous ventilation and offering a favorable hemodynamic profile in neonates. Its minimal impact on respiratory drive, combined with potential antiarrhythmic properties, made it a valuable adjunct in a patient at risk for perioperative arrhythmias.

This tailored pharmacologic approach allowed for a controlled transition from spontaneous to controlled ventilation, ensured hemodynamic stability, and reduced the risk of anesthetic-induced myocardial depression.

In anticipation of potential cardiovascular instability, we elected to place an arterial catheter in the left radial artery prior to induction, allowing for real-time blood pressure monitoring during anesthetic deepening and airway instrumentation. While pre-induction femoral or ECMO cannulation may be warranted in extreme cases, early invasive monitoring via radial access proved sufficient in this patient and provided a safe window during the transition from spontaneous breathing to full anesthetic depth[9].

The presence of ECG abnormalities and tumor involvement near the coronary artery increased the risk of perioperative arrhythmias[10]. Defibrillator pads were placed, and antiarrhythmic medications were readily available. TEE provided continuous insight into ventricular function, enabling rapid detection of wall motion abnormalities and valvular dysfunction during CPB weaning.

-

Conclusion

This case highlights the critical importance of a multidisciplinary and anticipatory strategy in the anesthetic management of neonatal cardiac tumors. The presence of an intrapericardial mass with potential for both airway and cardiovascular compromise demanded precise planning, early invasive monitoring, and pharmacologic choices tailored to preserve hemodynamic stability and spontaneous ventilation.

A high index of suspicion for arrhythmias, proactive preparation for rapid intervention, and continuous intraoperative cardiac assessment were pivotal in navigating the perioperative

period safely. The favorable outcome observed underscores how individualized anesthetic care, grounded in physiologic reasoning and interprofessional coordination, can significantly influence survival and recovery in such complex neonatal scenarios.

-

References

1. Butany J, Nair V, Naseemuddin A, Nair GM, Catton C, Yau T. Cardiac tumours: diagnosis and management. Lancet Oncol. 2005 Apr;6(4):219–28. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(05)70093-0 PMID:15811617

2. Hammer GB, Black AE. Anaesthetic management for the child with a mediastinal mass. Paediatr Anaesth. 2004 Jan;14(1):95–7. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1460-9592.2003.01196.x PMID:14717880

3. Isaacs H Jr. Fetal and neonatal cardiac tumors. Pediatr Cardiol. 2004;25(3):252–73. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00246-003-0590-4 PMID:15360117

4. Kim SJ, Park IS, Shin YW, et al. Surgical treatment of primary cardiac tumors in children: early and long-term results. Ann Thorac Surg. 2005;79(5):1882–7.

5. Berman W Jr, Bernbaum J, Bove EL. Anesthetic implications of primary cardiac tumors in infants and children. Anesth Analg. 1981;60(5):309–13.

6. Loomba RS, Gray SB, Flores S. Hemodynamic effects of ketamine in children with congenital heart disease and/or pulmonary hypertension. Congenit Heart Dis. 2018 Sep;13(5):646–54. https://doi.org/10.1111/chd.12662 PMID:30259660

7. de Kort EH, Twisk JW, van T Verlaat EP, Reiss IK, Simons SH, van Weissenbruch MM. Propofol in neonates causes a dose-dependent profound and protracted decrease in blood pressure. Acta Paediatr. 2020 Dec;109(12):2539–46. https://doi.org/10.1111/apa.15282 PMID:32248549

8. Yang C, Deng B, Wen Q, Guo P, Liu X, Wang C. Safety profiles of sevoflurane in pediatric patients: a real-world pharmacovigilance assessment based on the FAERS database. Front Pharmacol. 2025 Feb;16:1548376. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphar.2025.1548376 PMID:39995419

9. Fu J, Li H, Pan Z, Wu C, Li Y, Wang G, et al. Surgical treatment of primary cardiac tumors in children. Gen Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2024 Feb;72(2):112–20. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11748-023-01958-z PMID:37515628

10. Tan A, Nolan JA. Anesthesia for children with anterior mediastinal masses. Paediatr Anaesth. 2022 Jan;32(1):4–9. https://doi.org/10.1111/pan.14319 PMID:34714957

ORCID

ORCID