Martha Patricia Lázaro Ovalle1, Fabricio Andres Lasso Andrade2,* Pedro José Herrera Gómez2

Recibido: 28-09-2024

Aceptado: 29-12-2025

©2025 El(los) Autor(es) – Esta publicación es Órgano oficial de la Sociedad de Anestesiología de Chile

Revista Chilena de Anestesia Vol. 54 Núm. 6 pp. 846-850|https://doi.org/10.25237/revchilanestv54n6-09

PDF|ePub|RIS

Dolor agudo postoperatorio en cesárea y ligadura tubárica

Abstract

Background: Postoperative pain is a common complication in patients undergoing cesarean section and tubal ligation, affecting recovery and satisfaction. This study evaluates the intensity of postoperative pain at 2, 24, and 48 hours in patients who underwent cesarean section, cesarean with tubal ligation, or tubal ligation alone, under spinal anesthesia. Methods: A prospective cohort observational study was conducted in 73 patients at the Instituto Materno Infantil of Bogotá. Patients with pre-existing chronic pain or critical conditions were excluded. Postoperative pain was measured using the numeric pain scale at 2, 24, and 48 hours. Fisher’s exact test was used for categorical comparisons and the Wilcoxon test with continuity correction for ordinal variables, applying Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons. Results: At 2 hours postoperatively, 89% of patients reported no pain, while 20.5% experienced severe pain at 24 hours, and 16.5% reported severe pain at 48 hours. No statistically significant differences were found between pain levels at 24 and 48 hours (p = 0.4094). Furthermore, no significant differences were observed in pain levels between the three types of procedures (cesarean section, cesarean with tubal ligation, and tubal ligation alone) at any of the measured time points (2 hours, p = 0.1037; 24 hours, p = 0.9685; 48 hours, p = 0.88). Conclusion: Postoperative pain increased between 2 and 24 hours, remaining elevated at 48 hours, with no significant differences between procedures. The need to improve postoperative pain management regardless of the type of surgery is highlighted.

Resumen

Antecedentes: El dolor postoperatorio agudo es una complicación común en pacientes sometidas a cesárea y ligadura tubárica, afectando la recuperación y la satisfacción. Este estudio evalúa la intensidad del dolor posoperatorio a las 2, 24 y 48 h en pacientes sometidas a cesárea, cesárea con ligadura tubárica, o ligadura tubárica sola, bajo anestesia subaracnoidea. Métodos: Se realizó un estudio observacional de cohorte prospectivo en 73 pacientes del Instituto Materno Infantil de Bogotá. Se excluyeron pacientes con dolor crónico preexistente o en estado crítico. El dolor postoperatorio se midió utilizando la escala numérica del dolor a las 2, 24 y 48 h. Para el análisis estadístico se empleó la prueba exacta de Fisher para comparaciones categóricas y la prueba de Wilcoxon con corrección de continuidad para variables ordinales, aplicando corrección de Bonferroni en comparaciones múltiples. Resultados: A las 2 h postoperatorias, el 89% de las pacientes no reportaron dolor, mientras que el 20,5% experimentó dolor severo a las 24 h, y el 16,5% reportó dolor severo a las 48 h. No se encontraron diferencias estadísticamente significativas entre los niveles de dolor a las 24 y 48 h (p = 0,4094). Además, no se observaron diferencias significativas en los niveles de dolor entre los tres tipos de procedimientos (cesárea, cesárea con ligadura tubárica, y ligadura tubárica sola) en ninguno de los momentos medidos (2 h, p = 0,1037; 24 h, p = 0,9685; 48 h, p = 0,88). Conclusión: El dolor postoperatorio aumenta entre las 2 y 24 h, manteniéndose elevado a las 48 h, sin diferencias significativas entre los procedimientos. Se destaca la necesidad de mejorar el manejo del dolor postoperatorio independientemente del tipo de cirugía.

-

Introduction

Postoperative pain is a major concern in the management of patients undergoing surgical procedures such as cesarean section and tubal ligation. According to reports from the World Health Organization (WHO), annually, 18.5 million cesarean sections are performed globally, of which approximately 6 million are considered unnecessary. It is believed that the cesarean section rate should not exceed 15% anywhere in the world[1].

In Colombia, in 2016, the proportion of births by cesarean section was 46.4% at the national level, with a slight decrease to 44.6% by 2020. In public health institutions (IPS), the proportion of cesarean sections increased from 26.2% in 1998 to 42.9% in 2014, while in private institutions it increased from 45.0% to 57.7% in 2013. The prevalence ratio of cesarean sections in private institutions compared to public ones was 1.57 (95% CI: 1.56-1.57)[2]. In Brazil, between 2014 and 2017, it was observed that the cesarean section rate was 80.0% in patients without prenatal care, 45.2% in those with inadequate prenatal care, 43.0% for those with adequate care, and 50.5% in the group with “adequate plus” care[3], showing similar proportions of cesarean sections reported in Latin America. Cesarean section rates above 30% in Latin America are concerning due to their association with higher perioperative morbidity and mortality[4].

High-efficacy contraceptive measures, such as tubal ligation, can significantly contribute to improving post-cesarean morbidity and mortality rates. This procedure is increasingly common among women, especially in the immediate postpartum period, particularly in those with higher parity[5]. Tubal ligation not only offers a permanent contraceptive method but also reduces the risk of complications in future pregnancies[6].

Although these surgical procedures are considered to have lower pain scores, postoperative pain for tubal ligations has shown average scores of 4.74 and for cesarean section 6.14 on the numerical pain scale7. This pain is associated with decreased patient satisfaction, delayed ambulation, the development of chronic pain, and increased morbidity and mortality[8].

The primary objective of this study is to evaluate the intensity of acute postoperative pain in patients undergoing cesarean section, with or without tubal ligation, under spinal anesthesia. Secondary objectives include characterizing sociodemographic, clinical, and surgical variables, as well as pain management. Additionally, the study aims to establish relationships between pain intensity (mild, moderate, or severe) and the type of procedure performed, evaluating these parameters at three key postoperative moments, up to 48 hours after the procedure.

-

Methods

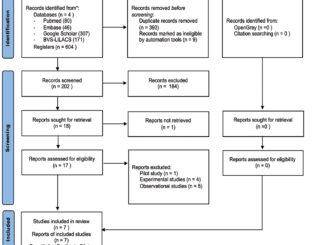

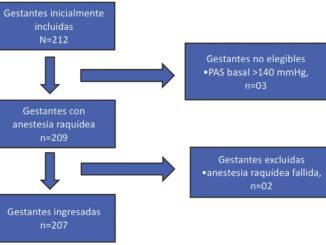

This prospective cohort observational study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Universidad Nacional de Colombia (act No. 011-191-17) and the Ethics and Research Committee of the Hospital Materno Infantil – Subred Centro Oriente (act No. 231 of November 27, 2017). It was conducted at the Maternal and Child Institute in Bogotá, where data were collected between November 2017 and 2018. Pregnant patients over 18 years old who underwent cesarean section with tubal ligation, cesarean section alone, or tubal ligation alone, all under spinal anesthesia, were included. Patients in critical condition with mechanical ventilation, postoperative neurological complications, pre-existing chronic pain, or those undergoing simultaneous surgeries were excluded.

Using a statistical power of 80%, an expected correlation of 0.5, a two-tailed hypothesis, and a significance level of 0.05, a minimum sample size of 56 participants was calculated[9]. Adjusting for a 20% non-response rate, a total of 73 participants were required. A form with three categories of information was used for prospective data collection: sociodemographic, clinical, and related to the surgical procedure and anesthesia. Follow-up was conducted from admission to the operating room until 48 hours after the surgical procedure. Postoperative pain intensity was measured upon admission to the post-anesthesia care unit, at 24 and 48 hours, using the numerical pain scale[10]. The collected physical data were stored in a file under the custody of the principal investigator. A Microsoft Excel® database was built for data processing and analysis, which was performed using the R programming language (R Foundation®).

The data were analyzed using descriptive statistics. Numerical variables were presented as means and standard deviations, while nominal and qualitative variables were expressed as absolute numbers and percentages. A bivariate analysis was performed to evaluate differences in pain levels between the different procedures (cesarean section, cesarean section with tubal ligation, and tubal ligation), using Fisher’s exact test[11], for categorical comparisons and the Wilcoxon test with continuity correction for ordinal variables[12]. In addition, Bonferroni correction was applied to adjust the significance values in multiple comparisons with a p-value of 0.017 for repeated measures comparison[13]. Bivariate results were considered statistically significant when the p-value was less than 0.05.

-

Results

In the analysis of sociodemographic and clinical data from the 73 patients, the average age was 26.5 ± standard deviation (SD) of 6.2, while the average body mass index (BMI) was 26.9 ± SD 3.9 kg/m2. Most procedures were tubal ligation (54.8%), followed by cesarean section (24.7%) and cesarean section with tubal ligation (20.5%). 82.2% of patients had between 1 and 3 previous pregnancies, and 90.4% had had between 1 and 3 vaginal deliveries. 52.1% of patients had no history of cesarean section, while 39.7% had had between 1 and 2 previous cesarean sections. Labor before the cesarean section occurred in only 21.2% of patients (Table 1).

For pre-cesarean analgesia, only 15.1% of patients received epidural anesthesia and 9.1% received intravenous anesthesia. The indication for cesarean section was elective in 72.3% of cases, while 27.7% were emergency cesarean sections. The most commonly used anesthetic technique was spinal anesthesia (98.6%), and in terms of neuroaxial opioids, an average of 19.2 ± 22.3 mcg of fentanyl and 54.5 ± 51.4 mcg of morphine were administered. The average surgical time was 32.2 ± 18 minutes, and intraoperative complications (hypotension, nausea, and vomiting) occurred in 6.8% of cases.

For intraoperative analgesia, the most frequently administered intravenous drug was diclofenac, which was used in 68.5% of patients, while 15.1% received dipyrone. In immediate postoperative analgesia, only 1.4% received diclofenac, and 43.8% received dipyrone. In terms of postoperative pain, 89% of patients reported no pain at 2 hours. At 24 hours, 13.7% of patients had no pain, and 20.5% had severe pain. At 48 hours, a similar distribution was observed, with only 12.3% having no pain, while 16.5% had severe pain.

In the bivariate analysis of pain levels in the post-anesthesia care unit (PACU) at 2 hours postoperatively, no statistically significant differences were found between the three types of procedures (cesarean section, cesarean section with ligation, and tubal ligation alone) at any of the observation times: 2, 24, and 48 hours (Table 2).

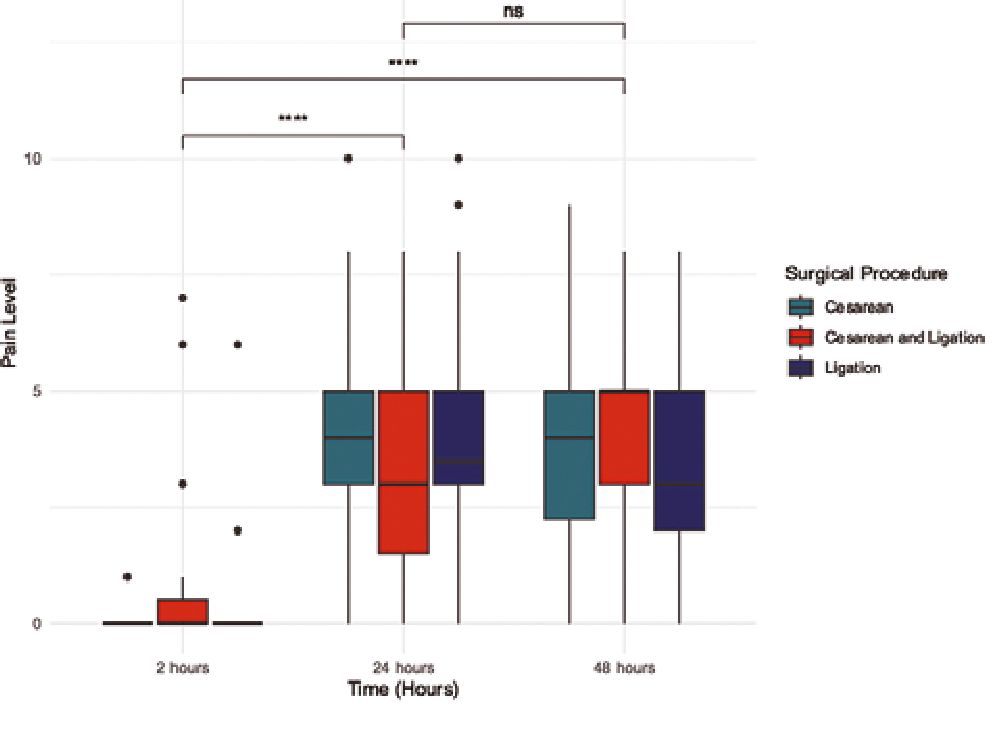

When comparing pain measurements at 2, 24, and 48 hours postoperatively, the Wilcoxon test with continuity correction was used, and applying the Bonferroni correction (p < 0.017), statistically significant differences were observed between pain levels at 2 hours and 24 hours (p < 0.01), as well as between 2 hours and 48 hours (p < 0.01). No significant differences were found in pain levels between 24 and 48 hours (p = 0.4094) (Figure 1).

Table 1. Sociodemographic and Clinical Characterization

| Characteristic | n = 73 (%) |

| Age (years) ± SD | 26.5 ± 6.2 |

| Weight (kg) ± SD | 67.1 ± 10.7 |

| Height (meters) ± SD | 1.58 ± 0.06 |

| BMI (kg/m2) ± SD | 26.9 ± 3.9 |

| Procedure | |

| – Cesarean section | 18 (24.7) |

| – Cesarean section and Tubal Ligation | 15 (20.5) |

| – Tubal Ligation | 40 (54.8) |

| Previous pregnancies | |

| – 1-3 | 60 (82.2) |

| – ≥4 | 13 (17.8) |

| Previous vaginal deliveries | |

| – 1-3 | 66 (90.4) |

| – 4 | 7 (9.6) |

| Previous cesarean sections | |

| – 0 | 38 (52.1) |

| – 1-2 | 29 (39.7) |

| – ≥3 | 6 (8.2) |

| Labor prior to cesarean section Pre-cesarean analgesia | 7 (21.2) |

| – Epidural | 5 (15.1) |

| – Intravenous | 3 (9.1) |

| Indication for cesarean section | |

| – Elective | 24 (72.3) |

| – Emergency | 9 (27.7) |

| Anesthetic technique | |

| – Spinal | 72 (98.6) |

| – Epidural | 1 (1.4) |

| Neuroaxial opioid | |

| – Fentanyl (mcg) ± SD | 19.2 ± 22.3 |

| – Morphine (mcg) ± SD | 54.5 ± 51.4 |

| Surgical time (minutes) ± SD | 32.2 ± 18 |

| Complications (Hypotension, nausea, and vomiting) | 5 (6.8) |

| Intraoperative analgesia | |

| – Diclofenac | 50 (68.5) |

| – Dipyrone | 11 (15.1) |

| Immediate postoperative analgesia | |

| – Diclofenac | 1 (1.4) |

| – Dipyrone | 32 (43.8) |

| Post-anesthesia care unit pain (2 hours) (NRS) | |

| Mean: 0.37 SD 1.33 Median 0 (IQR 0-0) | |

| – No pain (0) | 65 (89.0) |

| – Mild (1-3) | 5 (6.9) |

| – Moderate (4-6) | 2 (2.7) |

| – Severe (7-10) | 1 (1.4) |

| Pain at 24 hours (NRS) | |

| Mean: 4.03 SD 2.73 Median 4 (IQR 3-5) | |

| – No pain (0) | 10 (13.7) |

| – Mild (1-3) | 25 (34.3) |

| – Moderate (4-6) | 23 (31.5) |

| – Severe (7-10) | 15 (20.5) |

| Pain at 48 hours (NRS)

Mean: 3.85 SD 2.32 Median 4 (IQR 2-5) |

|

| – No pain (0) | 9 (12.3) |

| – Mild (1-3) | 25 (34.3) |

| – Moderate (4-6) | 27 (36.9) |

| – Severe (7-10) | 12 (16.5) |

SD: Standard Deviation; BMI: Body Mass Index; NRS: Numeric Rating Scale for pain; IQR: Interquartile Range.

Figure 1. Distribution of pain at 2, 24, and 48 hours by procedure. Comparisons of pain levels at 2, 24, and 48 hours using the Wilcoxon test with continuity correction. Bonferroni correction (p < 0.0167) was applied to adjust the significance values with 3 comparisons. **** The results showed statistically significant differences between pain levels at 2 hours and 24 hours (p < 0.01) and between 2 hours and 48 hours (p < 0.01). Ns: No significant difference was found between pain levels at 24 and 48 hours (p = 0.4094).

-

Discussion

This study showed that acute postoperative pain in the first 48 hours after the procedure does not vary significantly among patients undergoing cesarean section, cesarean section with tubal ligation, and tubal ligation alone. Two hours postoperatively, 89% of patients did not report pain, whereas at 24 hours, this percentage decreased to 13.7%, and 20.5% of patients reported severe pain. At 48 hours, only 12.3% of patients did not report pain, while 16.5% still experienced severe pain. These findings are consistent with previous studies indicating that postoperative pain in cesarean sections is a critical factor affecting recovery and patient satisfaction[14].

The bivariate analysis of pain levels between the three procedures showed that, at 2 hours, there were no statistically significant differences between the groups (p = 0.1037), reinforcing the idea that tubal ligation is not a procedure exempt from relevant postoperative pain. At 24 hours, no significant differences were found in pain levels among the three procedures (p = 0.9685), with mean pain scores of 4.2 for cesarean section, 3.5 for cesarean section with ligation, and 4.1 for tubal ligation. These data highlight the need to improve pain management strategies in all patients undergoing tubal ligation[15]. This suggests that postoperative pain does not depend on the procedure but on the time elapsed after surgery, which is consistent with existing literature on the evolution of postoperative pain in patients undergoing cesarean section and tubal liga- tion[16],[17].

This study presents some limitations that should be considered when interpreting the results. The relatively small sample size (n = 73) could affect the generalization of the results. However, the sample size calculation was adequate to maintain the accepted statistical power, aiming to reduce alpha and beta errors, thereby increasing the validity of the findings within this specific context. Another important limitation was the lack of long-term follow-up to assess the incidence of chronic postoperative pain, which is known to affect a significant percentage of women undergoing cesarean section. Future studies should explore different follow-up periods for patients undergoing tubal ligation to establish its association with potential persistent postoperative pain, with a larger sample size that could detect a statistical difference.

Table 2. Bivariate analysis of pain and procedure

| Type of Procedure (Mean ± SD) | Pain in PACU | Value p | |||

| 2 hours postoperatively | |||||

| No Pain | Mild | Moderado | Severo | ||

| Cesarean section

(0.1± 0.32) |

16 (88.9) | 2 (11.1) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| Cesarean section and Tubal Ligation (1.1 ± 2.32) | 11 (73.3) | 2 (13.3) | 1 (6.7) | 1 (6.7) | 0.1037* |

| Ligadura de trompas (0.2± 0.99) | 38 (95) | 1 (2.5) | 1 (2.5) | 0 (0) | |

| 24 hours postoperatively | |||||

| Cesarean section (4.2 ± 2.67) | 2 (11.1) | 5 (27.7) | 7 (38.9) | 4 (22.2) | |

| Cesarean section and Tubal Ligation (3.5 ± 2.77) | 3 (20) | 5 (33.3) | 4 (26.7) | 3 (20) | 0.9685* |

| Tubal Ligation (4.1 ± 2.78) | 5 (12.5) | 15 (37.5) | 12 (30) | 8 (20) | |

| 48 hours postoperatively | |||||

| Cesarean section

(3.9±2.46) |

2 (11.1) | 6 (33.3) | 7 (38,9) | 3 (16,7) | |

| Cesarean section and Tubal Ligation (4.2± 1.98) | 1 (6.7) | 4 (26.7) | 8 (53,3) | 2 (13,3) | 0.88* |

| Tubal Ligation (3.6 ± 2.39) | 6 (15) | 15 (37.5) | 12 (30) | 7 (17,5) | |

| PACU: Post-anesthesia care unit; *: Fisher’s exact test; SD: Standard deviation. | |||||

-

Conclusion

Acute postoperative pain did not show significant differences between cesarean section, cesarean section with ligation, and tubal ligation alone at 2 hours. However, there was an increase in pain intensity at 24 and 48 hours, highlighting the importance of postoperative pain management regardless of the surgical procedure. Funding This study has no funding source.

Conflict of Interest The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Dedication To the professors of the Universidad Nacional de Colombia for their contributions to our education.

-

References

1. Li YS, Lin SP, Horng HC, Tsai SW, Chang WK. Risk factors of more severe hypotension after spinal anesthesia for cesarean section. J Chin Med Assoc. 2024 Apr;87(4):442–7. https://doi.org/10.1097/JCMA.0000000000001056 PMID:38252496

2. Essam Elfeil Y, Alattar AM, Ghoneim TA, Abd Elaziz AR, Deghidy EA. The effectiveness of non invasive hemodynamic parameters in detection of spinal anesthesia induced hypotension during cesarean section. Alex J Med. 2021;57(1):121–9. https://doi.org/10.1080/20905068.2021.1885953.

3. Chekol WB, Melesse DY, Mersha AT. Incidence and factors associated with hypotension in emergency patients that underwent cesarean section with spinal anaesthesia: prospective observational study. Int J Surg Open. 2021;35(100378):100378. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijso.2021.100378.

4. Fitzgerald JP, Fedoruk KA, Jadin SM, Carvalho B, Halpern SH. Prevention of hypotension after spinal anaesthesia for caesarean section: a systematic review and network meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Anaesthesia. 2020 Jan;75(1):109–21. https://doi.org/10.1111/anae.14841 PMID:31531852

5. Xue X, Lv X, Ma X, Zhou Y, Yu N, Yang Z. Prevention of spinal hypotension during cesarean section: A systematic review and Bayesian network meta-analysis based on ephedrine, phenylephrine, and norepinephrine. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2023 Jul;49(7):1651–62. https://doi.org/10.1111/jog.15671 PMID:37170779

6. Yu C, Gu J, Liao Z, Feng S. Prediction of spinal anesthesia-induced hypotension during elective cesarean section: a systematic review of prospective observational studies. Int J Obstet Anesth. 2021 Aug;47(103175):103175. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijoa.2021.103175 PMID:34034957

7. Munyanziza T. Incidence of spinal anesthesia induced severe hypotension among the pregnant women undergoing cesarean section at Muhima hospital. Rwanda J Med Health Sci. 2022 Apr;5(1):62–70. https://doi.org/10.4314/rjmhs.v5i1.8 PMID:40641469

8. Huang Q, Wen G, Hai C, Zheng Z, Li Y, Huang Z, et al. A height-based dosing algorithm of bupivacaine in spinal anesthesia for decreasing maternal hypotension in cesarean section without prophylactic fluid preloading and vasopressors: A randomized-controlled non-inferiority trial. Front Med (Lausanne). 2022 Jun;9:858115. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmed.2022.858115 PMID:35755061

9. Kinsella SM, Carvalho B, Dyer RA, Fernando R, McDonnell N, Mercier FJ, et al.; Consensus Statement Collaborators. International consensus statement on the management of hypotension with vasopressors during caesarean section under spinal anaesthesia. Anaesthesia. 2018 Jan;73(1):71–92. https://doi.org/10.1111/anae.14080 PMID:29090733

10. Benjhawaleemas P, Sakolnagara BB, Tanasansuttiporn J, Chatmongkolchart S, Oofuvong M. Risk prediction score for high spinal block in patients undergoing cesarean delivery: a retrospective cohort study. BMC Anesthesiol. 2024 Nov;24(1):406. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12871-024-02799-w PMID:39528929

11. Bhat AD, Singh PM, Palanisamy A. Neuraxial anaesthesia-induced hypotension during Caesarean section. BJA Educ. 2024 Apr;24(4):113–20. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bjae.2024.01.003 PMID:38481416

12. Šklebar I, Bujas T, Habek D. Spinal anaesthesia-induced hypotension in obstetrics: prevention and therapy. Acta Clin Croat. 2019 Jun;58 Suppl 1:90–5. https://doi.org/10.20471/acc.2019.58.s1.13 PMID:31741565

13. Neumann C, Velten M, Heik-Guth C, Strizek B, Wittmann M, Hilbert T, et al. 5-HT3 blockade does not attenuate postspinal blood pressure change in cesarean section: A case-control study. Medicine (Baltimore). 2020 Sep;99(36):e21864. https://doi.org/10.1097/MD.0000000000021864 PMID:32899016

14. Massoth C, Töpel L, Wenk M. Hypotension after spinal anesthesia for cesarean section: how to approach the iatrogenic sympathectomy. Curr Opin Anaesthesiol. 2020 Jun;33(3):291–8. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACO.0000000000000848 PMID:32371631

15. van Dyk D, Dyer RA, Bishop DG. Spinal hypotension in obstetrics: context-sensitive prevention and management. Best Pract Res Clin Anaesthesiol. 2022 May;36(1):69–82. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bpa.2022.04.001 PMID:35659961

16. Huang B, Huang Q, Hai C, Zheng Z, Li Y, Zhang Z. Height-based dosing algorithm of bupivacaine in spinal anaesthesia for decreasing maternal hypotension in caesarean section without prophylactic fluid preloading and vasopressors: study protocol for a randomised controlled non-inferiority trial. BMJ Open. 2019 May;9(5):e024912. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2018-024912 PMID:31101694

17. Fakherpour A, Ghaem H, Fattahi Z, Zaree S. Maternal and anaesthesia-related risk factors and incidence of spinal anaesthesia-induced hypotension in elective caesarean section: A multinomial logistic regression. Indian J Anaesth. 2018 Jan;62(1):36–46. https://doi.org/10.4103/ija.IJA_416_17 PMID:29416149

18. Massoth C, Töpel L, Wenk M. Hypotension after spinal anesthesia for cesarean section: how to approach the iatrogenic sympathectomy. Curr Opin Anaesthesiol. 2020 Jun;33(3):291–8. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACO.0000000000000848 PMID:32371631

19. Tadesse Y, Moges K, Tarekegn F. Assessment of the magnitude and risk factors of post spinal relevant hemodynamics associated with caesarean section in Bahirdar university hospital, northwest Ethiopia, 2020. Journal of Anesthesia & Pain Medicine. 2022;7(1): https://doi.org/10.33140/JAPM.07.01.09.

20. Patel S, Ninave S. Postspinal anesthesia hypotension in Caesarean delivery: A narrative review. Cureus. 2024 Apr;16(4):e59232. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.59232 PMID:38813325

21. Erango M, Frigessi A, Rosseland LA. A three minutes supine position test reveals higher risk of spinal anesthesia induced hypotension during cesarean delivery. An observational study. F1000 Res. 2018 Jul;7:1028. https://doi.org/10.12688/f1000research.15142.1 PMID:30135733

22. Héctor Lacassie Q. HLQ, Altermatt C. F, Irarrázaval M. MJ, Kychenthal L. C, De La Cuadra F. JC. Anestesia espinal parte III. Mecanismos de acción. Rev Chil Anest. 2021;50(3):526–32. https://doi.org/10.25237/revchilanestv50n03-16.

23. Kaufner L, Karekla A, Henkelmann A, Welfle S, von Weizsäcker K, Hellmeyer L, et al. Crystalloid coloading vs. colloid coloading in elective Caesarean section: postspinal hypotension and vasopressor consumption, a prospective, observational clinical trial. J Anesth. 2019 Feb;33(1):40–9. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00540-018-2581-x PMID:30523408

24. Zwane SF, Bishop DG, Rodseth RN. Hypotension during spinal anaesthesia for Caesarean section in a resource- limited setting: towards a consensus definition. Southern African Journal of Anaesthesia and Analgesia. 2019;25(1):1–5. https://doi.org/10.1080/22201181.2018.1550872.

25. Bishop DG, Cairns C, Grobbelaar M, Rodseth RN. Obstetric spinal hypotension: preoperative risk factors and the development of a preliminary risk score – the PRAM score. S Afr Med J. 2017 Nov;107(12):1127–31. https://doi.org/10.7196/SAMJ.2017.v107i12.12390 PMID:29262969

26. Algarni RA, Albakri HY, Albakri LA, Alsharif RM, Alrajhi RK, Makki RM, et al. Incidence and risk factors of spinal anesthesia-related complications after an elective cesarean section: A retrospective cohort study. Cureus. 2023 Jan;15(1):e34198. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.34198 PMID:36843804

27. Shitemaw T, Jemal B, Mamo T, Akalu L. Incidence and associated factors for hypotension after spinal anesthesia during cesarean section at Gandhi Memorial Hospital Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. PLoS One. 2020 Aug;15(8):e0236755. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0236755 PMID:32790681

28. Yoezer T, Tenzin K, Tshering J, Than YM, Wangmo KP. Pre-delivery hypotension after spinal anesthesia during cesarean section and its associated factors at Jigme Dorji Wangchuck National Referral Hospital, Bhutan. Bhutan Health J. 2021;7(1):16–23. https://doi.org/10.47811/bhj.115.

29. López Hernández MG, Meléndez Flórez HJ, Álvarez Robles S, Alvarado Arteaga JL. Alvarado Arteaga J de L. Risk factors for hypotension in regional spinal anesthesia for cesarean section. Role of the Waist-to-Hip Ratio and Body Mass Index. Rev Colomb Anestesiol. 2018;46(1):42–8. https://doi.org/10.1097/CJ9.0000000000000008.

30. Mahajan S, Karnik H, Bajpai Y. A prospective study to identify the risk factors for hypotension after spinal anaesthesia in patients undergoing caesarean section. J Evid Based Med Healthc. 2019;6(38):2598–602. https://doi.org/10.18410/jebmh/2019/535.

31. Daly MJ, Borg-Xuereb K, Mandour Y. Is barbotage in central neuraxial blockade a ritual habit or an evidence-based technique? Br J Hosp Med (Lond). 2024 Jan;85(1):1–2. https://doi.org/10.12968/hmed.2023.0329 PMID:38300685

32. Jendoubi A, Khalloufi A, Nasri O, Abbes A, Ghedira S, Houissa M. Analgesia nociception index as a tool to predict hypotension after spinal anaesthesia for elective caesarean section. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2021 Feb;41(2):193–9. https://doi.org/10.1080/01443615.2020.1718624 PMID:32148136

33. Gousheh MR, Akhondzade R, Asl Aghahoseini H, Olapour A, Rashidi M. The effects of pre-spinal anesthesia administration of crystalloid and colloid solutions on hypotension in elective cesarean section. Anesth Pain Med. 2018 Aug;8(4):e69446. https://doi.org/10.5812/aapm.69446 PMID:30250818

34. Yeh PH, Chang YJ, Tsai SE. Observation of hemodynamic parameters using a non-invasive cardiac output monitor system to identify predictive indicators for post-spinal anesthesia hypotension in parturients undergoing cesarean section. Exp Ther Med. 2020 Dec;20(6):168. https://doi.org/10.3892/etm.2020.9298 PMID:33093906

35. Rukewe A, Orlam I, Akande A, Fatiregun AA. Distribution of cesarean delivery by Robson classification and predictors of postspinal anesthesia hypotension in Windhoek referral hospitals: A cross-sectional study. Niger J Clin Pract. 2022 Feb;25(2):178–84. https://doi.org/10.4103/njcp.njcp_573_20 PMID:35170444

36. Chooi C, Cox JJ, Lumb RS, Middleton P, Chemali M, Emmett RS, et al. Techniques for preventing hypotension during spinal anaesthesia for caesarean section. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2020 Jul;7(7):CD002251. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD002251.pub4 PMID:32619039

37. Yokose M, Mihara T, Sugawara Y, Goto T. The predictive ability of non-invasive haemodynamic parameters for hypotension during caesarean section: a prospective observational study. Anaesthesia. 2015 May;70(5):555–62. https://doi.org/10.1111/anae.12992 PMID:25676817

ORCID

ORCID