Ahmed Samir Saad MD.1, Rana Shalaby MSc.1, Ahmed Ibrahim Elsakka MD.1, Ashraf Abdelmoegoud MD.1, Reham Mahrous MD.1*

Recibido: 12-06-2025

Aceptado: 27-12-2025

©2025 El(los) Autor(es) – Esta publicación es Órgano oficial de la Sociedad de Anestesiología de Chile

Revista Chilena de Anestesia Vol. 54 Núm. 6 pp. 935-941|https://doi.org/10.25237/revchilanestv54n6-21

PDF|ePub|RIS

Impacto del tamaño de la aguja espinal en el bloqueo epidural por punción dural: ensayo aleatorizado

Abstract

Introduction: The combined spinal epidural technique (CSE) is recommended for labor analgesia as a better alternative to the conventional epidural technique (CE). It offers numerous advantages, such as profound analgesia, rapid onset, and elevated patient satisfaction levels. Objectives: To assess the safety and efficacy of the dural puncture epidural (DPE) technique, utilizing either 27-gauge (DPE-27) or 25-gauge (DPE-25) pencil point spinal needles compared to the CE technique. Material and Methods: A total of 81 patients were randomized into three groups (27 patients each). Group CE, Group DPE-25 (utilizing a 25-G spinal needle), and Group DPE-27 (utilizing a 27-G spinal needle). The onset of analgesia was the primary outcome (defined as the interval from the administration of the initial epidural bolus until reaching a visual analog scale score of < 3). Secondry outcomes included the degree of analgesia, hemodynamics variables, sensory level, motor block, and complications. Results: The DPE groups using 27-and 25-G spinal needles had a significantly faster onset compared to CE group (p < 0.001). Nevertheless, there were no variations between the two DPE groups in terms of analgesia onset. Conclusions: Although both techniques are efficacious for labor analgesia in primigravida, 25-G and 27-G Whitacre dural puncture epidural technique may benefit the nulliparous parturient more by improving the onset of analgesia and sacral spread compared to the conventional epidural technique. We recommend the usage of 27-G needle over 25-G as both have the same efficacy, but the incidence of post-dural puncture headache is lesser with the former.

Resumen

Introducción: La técnica epidural espinal combinada (EEC) se recomienda para la analgesia del parto como mejor alternativa a la técnica epidural convencional (TEC). Ofrece numerosas ventajas, como analgesia profunda, inicio rápido y elevados niveles de satisfacción de la paciente. Objetivos: Evaluar la seguridad y eficacia de la técnica epidural de punción dural (DPE), utilizando agujas espinales de punta de lápiz de calibre 27 (DPE-27) o de calibre 25 (DPE-25) en comparación con la técnica CE. Material y Métodos: Un total de 81 pacientes fueron distribuidos aleatoriamente en tres grupos (27 pacientes cada uno). Grupo CE, Grupo DPE-25 (con una aguja espinal de 25G) y Grupo DPE-27 (con una aguja espinal de 27G). El inicio de la analgesia fue el resultado primario (definido como el intervalo desde la administración del bolo epidural inicial hasta alcanzar una puntuación en la escala analógica visual < 3). Los resultados secundarios incluyeron el grado de analgesia, las variables hemodinámicas, el nivel sensorial, el bloqueo motor y las complicaciones. Resultados: Los grupos de DPE que utilizaron agujas espinales de 27 y 25G tuvieron un inicio significativamente más rápido en comparación con el grupo CE (p < 0,001). No obstante, no hubo variaciones entre los dos grupos de PED en cuanto al inicio de la analgesia. Conclusiones: Aunque ambas técnicas son eficaces para la analgesia del parto en primigrávidas, la técnica epidural de punción dural de Whitacre 25G y 27G puede beneficiar más a la parturienta nulípara al mejorar el inicio de la analgesia y la extensión sacra en comparación con la técnica epidural convencional. Recomendamos el uso de la aguja de 27G frente a la de 25G, ya que ambas tienen la misma eficacia, pero la incidencia de cefalea pospunción dural es menor con la primera.

-

Introduction

Labor pain is a highly painful experience for females, and the severity of the pain typically exceeds the anticipations of patients[1]. CSE has been recommended for labor analgesia over the CE technique due to numerous advantages, including elevated rates of patient satisfaction, profound analgesia, and rapid onset[2]. Nevertheless, the CSE technique carries the risk of inducing fetal bradycardia, hemodynamic instability, and other adverse effects associated with intrathecally administrated local opioids and anesthetics[2].

In order to mitigate these negative effects while maintaining the benefits, an innovative approach to DPE has been proposed. The DPE technique is a modified alternative to the CSE technique, in which a dural perforation is made utilizing a spinal needle. However, intrathecal medication injections have not been conducted. The procedure involves making a dural perforation with a spinal needle inserted through an epidural needle shaft. The catheter is subsequently inserted into the epidural space[3].

The DPE facilitates the conduit of medications (from the epidural to the subarachnoid spaces), and this mechanism is thought to be the cause of the distinctive attributes observed during the DPE procedure[4]. In addition, its efficacy in enhancing the initiation and delivery of analgesia and anesthesia in the sacral region has been proven. These characteristics are especially beneficial in obstetric patients[5].

Furthermore, Bernards et al., utilized a primate model to illustrate that medication delivered through the epidural route can flow into the subarachnoid space after dural puncture utilizing 18-25-G needles. They also determined that the delivery of medications administered epidurally to the sub-arachnoid space is directly influenced by the drug’s diffusion capacity, the dural hole’s size, and the distance between the puncture site until the administration of epidural drugs[6].

A previous study investigated the use of 27, 26, and 25-G Whitacre needles in parturient women (for spinal anesthesia) and revealed that 27-G needles demonstrated reduced rates of effective dural puncture. Nevertheless, no differences in the rates of dural puncture success were found between 26 and 25-G needles[7].

In contrast, extensive prospective trials proposed that 25-G needles (pencil point) might induce an increased occurrence of post-meningeal puncture headache compared to the 27-G ones[8].

These studies indicate that the existing evidence on DPE for labor analgesia is still unclear. Further research should explore the most effective size of spinal needle for DPE.

In this study, our objective was to formally compare the DPE and EP techniques, utilizing either 27 or 25-G spinal needles. In addition, we aimed to assess block efficacy and safety.

-

Material and Methods

-

Ethical considerations

This study was carried out at the Faculty of Medicine, Cairo University, Egypt, between January 2021 and January 2022. The study protocol was approved by the Ethical Committee at the Faculty of Medicine, Cairo University, Egypt. A written informed consent was taken from each patient prior to surgery.

-

Randomization

The randomization process involved the use of computergenerated numbers and the concealment of these numbers within sequentially numbered, opaque, and sealed envelopes. The investigators (who assessed the outcome of the procedure) and the patients were blinded to the details of the series. The nurse unsealed the appropriate numbered envelope prior to the surgery, and the card inside determined the patient’s group.

-

Eligibility criteria

The study was conducted on 81 primigravida parturient patients with ASA grade II who were in active labor with cervical dilatation < 5 cm, normal pregnancy, and vertex presentation.

Exclusion criteria included bleeding disorders, local anesthetic drug hypersensitivity, low platelet count, prior surgery in the lumbosacral spine, systemic or local sepsis, and patient refusal.

We enrolled a total of 81 females who fulfilled the inclusion criteria, and then subjects were equally randomized into three cohorts as follows:

Group CE (n = 27): Conventional epidural.

Group DPE-25 (n = 27): DPE utilizing a 25-G spinal needle.

Group DPE-27 (n = 27): DPE utilizing a 27-G spinal needle.

The patient’s complete surgical and medical history was obtained and recorded. An evaluation was conducted to assess

the airways and general systems. Laboratory tests were revised.

Prior to the initiation of the surgery, the patient was instructed on the use of VAS. This scale was then completed by the patient during the procedure to evaluate the intensity of pain.

VAS is a one-dimensional assessment tool for measuring the degree of pain. It consists of a straight horizontal line, typically 10 cm in length, with 0 representing no pain and 10 representing severe pain.

Within the operating room, an IV catheter was inserted, and the patient was thoroughly monitored. A 15-minute intravenous infusion of lactated Ringer’s solution (1L) was done throughout the neuraxial procedure.

A senior anesthesia resident performed the procedure while the patient was seated. Before the administration of the epidural and during an active contraction, participants indicated their pain level (on VAS). It is worth noting that parturients with VAS < 5 were excluded.

-

Conventional epidural group

In the epidural group, the epidural space was determined with the patient seated at the L3-L4 or L2-L3 interspace (utilizing the midline approach). Following the injection of 1% lidocaine (3 mL) into the skin, an 18-G Tuohy needle (Braun Perifix) was inserted and moved forward until a noticeable decrease in resistance to air was felt. Then, an 18-G multi-orifice catheter was passed through the epidural needle tip and moved forward 5 cm into the epidural space. Following negative aspiration for CSF and blood, a test dose (3 mL; 1.5% lidocaine) was injected to verify subarachnoid or intravascular catheter placement. The epidural catheters were subsequently administered with a 15-mL bolus (consisting of 50 pg fentanyl and 0.125% bupivacaine) in 5-mL portions. A waiting period of 2 minutes was observed between each dose, during which the patient was monitored for any indications of intravascular injections. This was done by asking the patient if she experienced dizziness, tinnitus, or any other signs of bradycardia or hypotension.

Motor weakness was assessed by inquiring about any clinical indications of subarachnoid space injection encountered by the patient. The dose was designated as the initial bolus dose, whereas the time of injection completion was recorded as time zero.

Following that, an infusion of epidural analgesia was initiated at 10 mL/h rate (fentanyl (2 pg/mL) with bupivacaine 0.125%). No further epidural boluses were given within the first 20 minutes.

-

Dural puncture epidural group

In the DPE groups, the epidural space was identified using an 18G Tuohy needle. Then, either a 27-G or 25-G Whitacre needle (Becton-Dickinson) was utilized to puncture the dura. This was done by inserting the Whitacre needle into the shaft of the previously placed epidural needle. This puncture aimed to produce a single dural puncture and verify CSF free flow. Once the flow of CSF was confirmed, the needle was removed, followed by the insertion of an epidural catheter in the same manner as in the CE group. The latter was taken out, and thereafter, the epidural catheter was anchored to the skin. Following that, the initial bolus dose and the successive infusion doses were identical to those administered in the epidural group.

Prior to drug administration (via the epidural catheter), subdural, intravascular, and subarachnoid placement were excluded. Prior to each dose, it was necessary to validate the proper positioning of the catheter.

Prior to each injection, aspiration was performed through the epidural catheter to ensure there was no CSF leakage. If the catheter is placed in the subarachnoid space, the intrathecal injection can cause a significant motor block. However, recent evidence indicates that this effect may not always be reliable. If there is a shift in the heart rate of 20% or more within 1 minute, it indicates that the catheter has moved into a blood vessel and needs to be replaced.

After a duration of 5 minutes following the administration of the initial bolus dose, analgesia adequacy was evaluated. Analgesia was deemed adequate if the VAS score was < 3. Analgesia onset was considered the period from the administration of the initial bolus dose to the point at which the patient achieved a VAS score of < 3. Moreover, a VAS score > 3 was deemed a failed block and then excluded from the study.

An observer who was blinded to the study procedures assessed the VAS scores, motor blockade, sensory levels, and onset of analgesia.

-

Study outcomes

Our primary outcome was the onset of analgesia (defined as duration from injection of the first initial epidural bolus dose to attainment of VAS < 3).

Secondry outcomes included:

1) Analgesia onset (the interval from the first epidural bolus injection until reaching a VAS < 3).

2) Vital signs (MABP and HR) which were recorded prior to the epidural (0 min-baseline). Subsequently, measurements were taken every 5 minutes until 15 minutes, then every 15 minutes until 1 hour, and finally every 1 hour until delivery. After each participant indicated their response on the VAS scale, they were asked about the presence of a contraction.

3) Visual analogue scale.

4) Sensory level following 30 mins of the block (by loss of cold sensation and blunt pinprick).

5) The motor block which was assessed through the modified Bromage scale 9 after 30 minutes of the block. The Bromage motor blockade score is 0, Free movement; 1, capable of flexing knees with free foot movement; 2, capable of flexing knees with free foot movement; and 3, capable of moving feet or legs.

6) The occurrence of adverse effects as:

The occurrence of adverse effects, including pruritus, hypotension, nausea, bradycardia, and vomiting, was evaluated within the first 20 minutes. Maternal hypotension is characterized as systolic blood pressure < 90 mm Hg or a reduction in average arterial pressure > 20% of the baseline value. Furthermore, the incidence of nerve injury and postdural puncture headache (PDPH) was documented within a time frame of 24 to 48 hours. The identification of nerve injury was based on the presence of sensory or motor impairment, as well as patient-reported complaints.

-

Sample size

In 2017, Chau et al. 3 illustrated that DPE had a substantial ly higher bilateral S2 blockade occurrence at 10 min compared to EPL (95% CI 1.39-3.28; risk ratio 2.13; P < 0.001). For the EPL Group, the S2 blockade probability at 10 min was 37.5%. Based on our calculations, a minimum sample size of 72 patients is necessary in order to reject the null hypothesis with 80% power (p = 0.2) and 95% significance level (a = 0.05). In order to accommodate an anticipated dropout rate of 10%, the calculated sample size was augmented by approximately 81 patients, leading to the formation of three groups of equal size, each consisting of 27 patients.

-

Statistical analysis

Data coding and statistical analysis were done utilizing the 28th version of the SPSS software (IBM Corp., Armonk-NY- USA). For normally distributed quantitative variables, data was expressed utilizing mean and standard deviation. In contrast, interquartile range and median were utilized for variables with non-normal distribution, whereas relative frequencies (percentages) and frequencies (number of cases) were utilized to express categorical variables. Group comparisons were conducted utilizing analysis of variance (ANOVA) with a post hoc test for multiple comparisons in normally distributed quantitative variables. Mann-Whitney and non-parametric Kruskal-Wallis tests were employed to analyze quantitative variables with non-normal distribution. The Chi-square test was utilized to compare categorical data. The exact test was used instead when the expected frequency was < 5. P-values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

-

Results

Eighty-one patients were enrolled in this study. Three patients were excluded because they reached full cervical dilation (within 1 hr) following the procedure (n = 3). Therefore, a total of 78 cases were included in the analysis. The CE Group (n = 26), the dural puncture epidural-25 (DPE-25) group (n = 27), and the dural puncture epidural-27 (DPE-27) group (n = 25).

The three cohorts exhibited similar demographic characteristics: BMI (kg/m2), height (cm), age (years), and weight (kgs), as well as obstetric data, including cervical dilatation and gestational age (p > 0.05). There were no intergroup variations in intervertebral puncture level and technical parameters (p = 0.946). Furthermore, there were insignificant differences between the three groups regarding the need for epidural top-up boluses (p = 0.879) (Table 1).

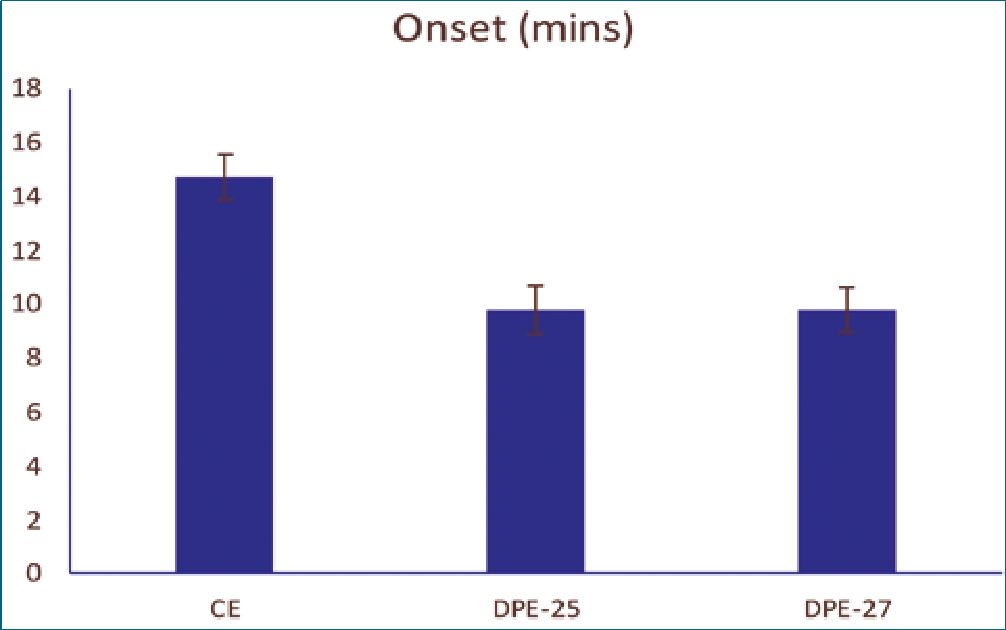

The DPE groups, using 25- and 27 G spinal needles, demonstrated a more rapid onset compared to the CE Group (p < 0.001). However, there were no variations in onset between the two DPE groups (p > 0.99). The average time until achieving adequate analgesia (VAS < 3) was 9.81 minutes in Group DPE- 25 and 9.8 minutes in Group DPE-27, significantly less than 14.69 minutes in the CE Group, and this difference reached statistical significance (P-value < 0.05) (Figure 1).

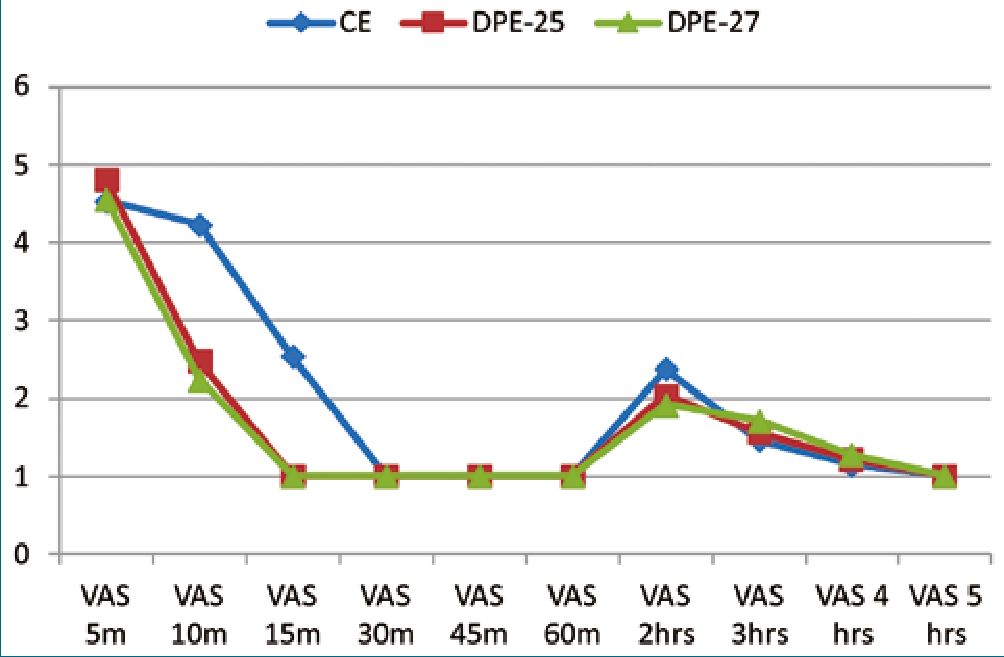

There were no variations in motor blockade degree. Throughout the trial, all patients had a Bromage score of 0, except for one patient in the CE Group, who had a Bromage score of 1-2 for the first hour of analgesia. However, it resolved to a Bromage score of 0 (p = 0.654). The mean VAS parturient score was 4.23 ± 0.43 in the CE group, 2.48 ± 0.58 in DPE-25, and 2.24± 0.44 in DPE-27 at minute 10. Conversely, it was 2.54 ± 0.51 in the CE group, 1 ± 0 in DPE-25, and 1 ± 0 in DPE-27 at minute 15. These results denote marked differences between the CE group and the other two DPE groups at minutes 10 and 15. (p < 0.05). However, these differences did not reach statistical significance at any other time (Figure 2).

Figure 1. Onset of analgesia among the three groups.

Table 1. Demographic and technical parameters

| CE n = 26 | DPE-25 n = 27 | DPE-27 n = 25 | P value | ||

| Age | 26.23 (1.07) | 26.19 (1.08) | 26.2 (1.08) | 0.988 | |

| BMI | 30.61 (1.63) | 30.97 (0.91) | 30.8 (1.49) | 0.637 | |

| Gestational age | 38.38 (0.5) | 38.48 (0.51) | 38.44 (0.51) | 0.783 | |

| Cervical dilatation | 3 cm | 12 (46.2) | 8 (29.6) | 9 (36) | 0.456 |

| 4 cm | 14 (53.8) | 19 (70.4) | 16 (64) | ||

| L2-L3 | 4 (15.4) | 3 (11.1) | 3 (12) | ||

| L3-L4 | 9 (34.6) | 12 (44.4) | 9 (36) | 0.946 | |

| L4-L5 | 13 (50) | 12 (44.4) | 13 (52) | ||

| Top up dose | 22 (84.6) | 21 (77.8) | 20 (80) | 0.879 | |

Data are expressed as mean (standard deviation) or number (percentage) as appropriate; BMI: body mass index.

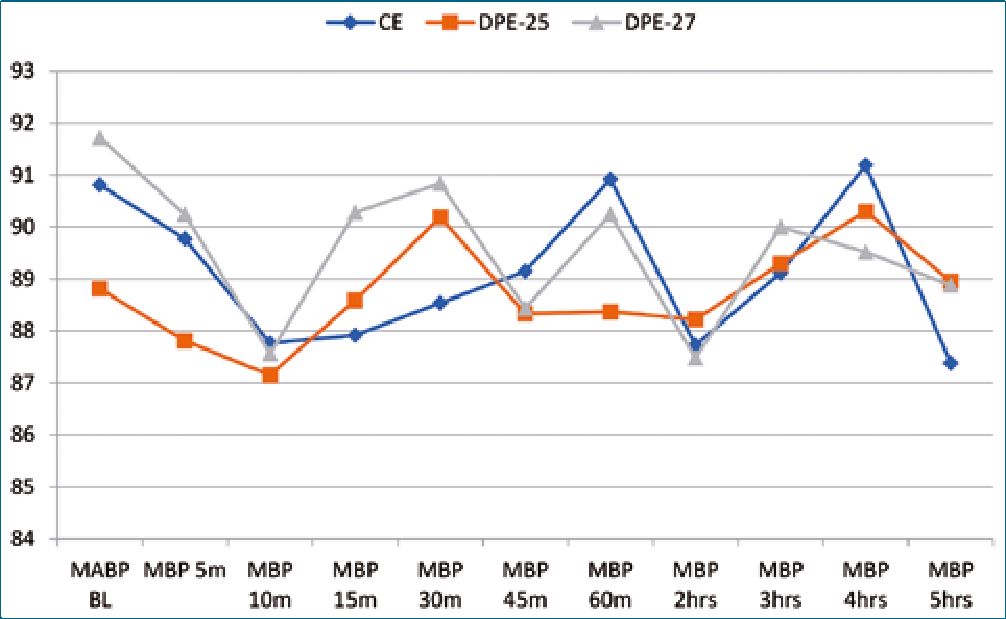

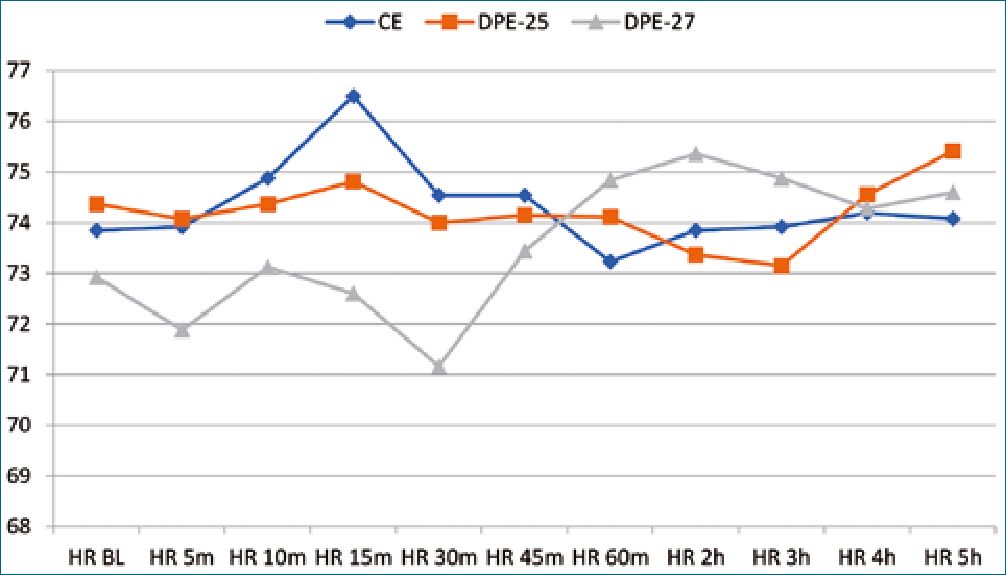

By comparing the three groups, no substantial differences were detected in the hemodynamics (heart rate & blood pressure) from the baseline until the end between the three groups (p > 0.05) (Figures 3 and 4).

The incidence of pruritus, bradycardia, vomiting, hypotension, and nausea was low, with no marked variation between the three groups. Additionally, two cases in the CE Group had hypotension, one occurring in the DPE-25 and the other in the DPE-27. This was resolved by administering a single 10 mg

ephedrine dose. The symptoms of pruritus and nausea were so slight that they did not necessitate any form of treatment. Regarding PDPH, there was no significant variation between the studied groups (p = 0.22) (Table 2).

Figure 2. Intraoperative Visual Analog Scale (VAS) among the three groups.

Figure 3. Mean arterial pressure (MBP) among the three groups.

Figure 4. Heart rate (HR) among the three groups.

Table 2. Incidence of postoperative and intraoperative complications

| CE n = 26 | DPE-25 n = 27 | DPE-27 n = 25 | P value | |

| Hypotension | 2 (7.7) | 1 (3.7) | 1 (4) | 0.84 |

| Bradycardia | 0 | 0 | 0 | – |

| Nausea | 2 (7.7) | 0 | 0 | 0.208 |

| Vomiting | 0 | 0 | 0 | – |

| Pruritis | 0 | 3 (11.1) | 2 (8) | 0.273 |

| PDPH | 0 | 6 (22.2) | 3 (12) | 0.22 |

| Data are expressed | as numbers (percentage); PDPH: | post-dural puncture headache. |

-

Discussion

Labor pain is a distressing experience that necessitates specialized care for women in labor in order to enhance their sat- isfaction[10]. In the current study, we aimed to compare the CE technique versus the DPE technique utilizing either 25- or 27-G pencil-point spinal needles during labor in terms of block efficacy and complications resulting from the dural puncture. We evaluated whether the DPE technique also improves labor analgesia onset and spread.

Our findings indicated an improvement in labor analgesia onset, with the DPE groups showing an earlier onset. Several authors have advocated for the use of CSE over the CE approach for labor analgesia due to profound analgesia, its rapid onset, and elevated patient satisfaction[2].

There is a debate concerning the superiority of the DPE technique (for labor analgesia) over the CE technique. However, our results align with Cappiello et al., who observed that 85% of patients reported a VAS < 1 at minute 20 following DPE ( a 25-G spinal needle), compared to 65% of patients who underwent CE[5]. In our study, at minutes 10 and 15, there was a significant variation between the CE group and both DPE groups. This difference may be attributed to the faster onset observed in the DPE groups.

Contreras et al., conducted a study comparing two separate sizes of spinal needles in DPE. The 25-G spinal needle resulted in a 1.6-minute reduction in onset time compared to the 27-G spinal needles. Moreover, the authors determined that while the observed difference was statistically significant, it may not have practical significance in a clinical setting. They recommended further studies to collect more evidence and validate their findings[11].

Our findings indicate that there is no discernible difference in the size of the holes created by 25-G and 27-G spinal needles during DPE in terms of onset. Nevertheless, both techniques surpassed the CE technique. Despite the apparent logic that a larger hole would facilitate the passage of a greater quantity of drug across the dural puncture, there was a debate regarding the DPE technique’s effectiveness and the needle’s size.

Thomas et al., found that there were no notable disparities in the effectiveness of labor epidural analgesia, such as unilateral block, inadequacy, the number of top-up doses needed, or sacral sparing while utilizing a 27-G Whitacre needle for dural puncture[12].

Nevertheless, Yadav et al. utilized a 27-G Whitacre needle and determined that DPE has the capacity to expedite onset and enhance labor analgesia quality compared to the CE tech- nique[13]. Suzuki et al.[4], additionally pointed out that a dural puncture (with a 26-G Whitacre spinal needle) led to faster onset as well as improved sacral spread following 2% mepivacaine (18 mL) for knee arthroscopy. Moreover, no alterations were observed in the cephalad anesthesia level.

With respect to the epidural doses needed, epidural catheters in our study were dosed with a 15-mL bolus (50 pg fentanyl with 0.125% bupivacaine), and then epidural infusion was started (bupivacaine 0.125% with 2 pg/mL fentanyl) at 10 mL/h. In contrast, Thomas used a 10 mL epidural dose (lidocaine 2%) and bupivacaine 0.11% infusion with 2 pg/mL fentanyl. Therefore, the variation in the types and dosages of local anesthetics employed could account for the discrepancy observed in the findings of the two studies[12].

Furthermore, it seems that even when using anesthetic epidural mepivacaine dosages, only a minimal quantity passed through the 26-G dural hole. A more extensive local anesthetic administration was anticipated to result in a faster sacral and maybe increased cephalad sensory blockade[4].

According to a recent review, DPE offers a more rapid onset of analgesia, declined incidence of asymmetric block, early bilateral sacral analgesia, and fewer maternal and fetal side effects than CE[14].

The occurrence of potential issues related to a dural puncture was equal in both groups in our study. However, regarding the post-dural puncture headache, there was a statistically significant difference between the CE group and the DPE-25 (p = 0.023). These results are inconsistent with the Yadav et al., study, which showed no statistically significant difference regarding the PDPH[13]. This difference may be elucidated by the utilization of a 25-G needle with a larger diameter in the current investigation, as opposed to the 27-G needle utilized by Yadav P.

-

Conclusion

In summary, our findings suggest that although both techniques are efficacious for labor analgesia in primigravida, 25-G and 27-G Whitacre dural puncture epidural technique may benefit the nulliparous parturient more by improving the onset of analgesia and sacral spread compared to the conventional epidural technique.

We recommend the usage of 27-G needle over 25-G as both have the same efficacy, but the incidence of PDPH is lesser with the former.

-

Limitations

1. Limited sample size.

2. Single center trial.

Publication Ethics

This study has not been sent to another scientific journal.

This study adheres to bioethical principles, and the authors guided their investigation by the ethical principles of the World Medical Association and the Helsinki statement.

The privacy and anonymity of the patients were ensured.

Funding None.

Conflicts of interests None.

Copyright Transfer Agreement (CTA)

The authors assign the intellectual property rights of the article to the Chilean Journal of Anesthesiology

-

References

1. Melzack R. The myth of painless childbirth (the John J. Bonica lecture). Pain. 1984 Aug;19(4):321–37. https://doi.org/10.1016/0304-3959(84)90079-4 PMID:6384895

2. Cook TM. Combined spinal-epidural techniques. Anaesthesia. 2000 Jan;55(1):42–64. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2044.2000.01157.x PMID:10594432

3. Chau A, Bibbo C, Huang CC, Elterman KG, Cappiello EC, Robinson JN, et al. Dural Puncture Epidural Technique Improves Labor Analgesia Quality With Fewer Side Effects Compared With Epidural and Combined Spinal Epidural Techniques: A Randomized Clinical Trial. Anesth Analg. 2017 Feb;124(2):560–9. https://doi.org/10.1213/ANE.0000000000001798 PMID:28067707

4. Suzuki N, Koganemaru M, Onizuka S, Takasaki M. Dural puncture with a 26-gauge spinal needle affects spread of epidural anesthesia. Anesth Analg. 1996 May;82(5):1040–2. https://doi.org/10.1097/00000539-199605000-00028 PMID:8610864

5. Cappiello E, O’Rourke N, Segal S, Tsen LC. A randomized trial of dural puncture epidural technique compared with the standard epidural technique for labor analgesia. Anesth Analg. 2008 Nov;107(5):1646–51. https://doi.org/10.1213/ane.0b013e318184ec14 PMID:18931227

6. Bernards CM, Kopacz DJ, Michel MZ. Effect of needle puncture on morphine and lidocaine flux through the spinal meninges of the monkey in vitro. Implications for combined spinal-epidural anesthesia. Anesthesiology. 1994 Apr;80(4):853–8. https://doi.org/10.1097/00000542-199404000-00019 PMID:8024140

7. Landau R, Ciliberto CF, Goodman SR, Kim-Lo SH, Smiley RM. Complications with 25-gauge and 27-gauge Whitacre needles during combined spinal-epidural analgesia in labor. Int J Obstet Anesth. 2001 Jul;10(3):168–71. https://doi.org/10.1054/ijoa.2000.0834 PMID:15321605

8. Fama’ F, Linard C, Bierlaire D, Gioffre’-Florio M, Fusciardi J, Laffon M. Influence of needle diameter on spinal anaesthesia puncture failures for caesarean section: A prospective, randomised, experimental study. Anaesth Crit Care Pain Med. 2015 Oct;34(5):277–80. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.accpm.2015.05.005 PMID:26453527

9. Bromage PR, Bramwell RS, Catchlove RF, Belanger G, Pearce CG. Peridurography with metrizamide: animal and human studies. Radiology. 1978 Jul;128(1):123–6. https://doi.org/10.1148/128.1.123 PMID:663198

10. Alleemudder D, Kuponiyi Y, Kuponiyi C, McGlennan A, Fountain S, Kasivisvanathan R. Analgesia for labour: an evidence-based insight for the obstetrician. Obstet Gynaecol. 2015;17155(3):147–55. https://doi.org/10.1111/tog.12196.

11. Contreras F, Morales J, Bravo D, Layera S, Jara Á, Riaño C, et al. Dural puncture epidural analgesia for labor: a randomized comparison between 25-gauge and 27-gauge pencil point spinal needles. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2019 May;44(7):rapm-2019-100608. https://doi.org/10.1136/rapm-2019-100608 PMID:31118278

12. Thomas JA, Pan PH, Harris LC, Owen MD, D’Angelo R. Dural puncture with a 27-gauge Whitacre needle as part of a combined spinal-epidural technique does not improve labor epidural catheter function. Anesthesiology. 2005 Nov;103(5):1046–51. https://doi.org/10.1097/00000542-200511000-00019 PMID:16249679

13. Yadav P, Kumari I, Narang A, Baser N, Bedi V, Dindor B. Comparison of dural puncture epidural technique versus conventional epidural technique for labor analgesia in primigravida. J Obstet Anaesth Crit Care. 2018;824(1):24. https://doi.org/10.4103/joacc.JOACC_32_17.

14. Gunaydin B, Erel S. How neuraxial labor analgesia differs by approach: dural puncture epidural as a novel option. J Anesth. 2019 Feb;33(1):125–30. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00540-018-2564-y PMID:30293143

ORCID

ORCID