Fabricio Andrés Lasso Andrade1,2,3 Juan Felipe Valdés Sanabria4,5, Gabriela Figueiras6, Jhonny Bustos Calvo4,7

Recibido: 14-06-2025

Aceptado: 01-08-2025

©2026 El(los) Autor(es) – Esta publicación es Órgano oficial de la Sociedad de Anestesiología de Chile

Revista Chilena de Anestesia Vol. 55 Núm. 1 pp. 17-28|https://doi.org/10.25237/revchilanestv55n1-03

PDF|Ir a Supplementary

Sulfato de magnesio en dolor neuropatico: Revisión sistémica y metaanalisis

Abstract

Background: Although magnesium sulfate has demonstrated analgesic properties in postoperative settings, its efficacy for neuropathic pain remains uncertain. This systematic review aimed to assess its potential therapeutic role in the management of neuropathic pain. Methods: We conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials comparing magnesium sulfate (administered orally or intravenously) with placebo or other neuromodulators in adults with neuropathic pain. Literature searches were performed in PubMed, EMBASE, Google Scholar, and BVS-LILACS from 1990 to May 2023. Risk of bias was assessed using the Cochrane Risk of Bias 2.0 tool. Pooled mean differences and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were estimated using a random-effects model (Mantel-Haenszel method). Heterogeneity was quantified using the I2 statistic. Results: Seven trials including a total of 274 participants were included. Compared to placebo, magnesium sulfate showed a nonsignificant reduction in pain scores (mean difference: -1.13; 95% CI: -2.64 to 0.38), with substantial heterogeneity (I2 = 81%). In comparisons with ketamine, a known NMDA receptor antagonist, magnesium sulfate also showed a non-significant mean difference of -0.67 (95% CI: -1.84 to 0.49), with moderate heterogeneity (P = 62%). Conclusions: Magnesium sulfate may hold potential as a therapeutic option for neuropathic pain; however, current evidence is insufficient to support its routine use. Further well-designed primary studies are needed to determine its efficacy, optimal dosing strategies, and appropriate clinical indications.

Resumen

Antecedentes: Aunque el sulfato de magnesio ha demostrado propiedades analgésicas en contextos posoperatorios, su eficacia para el dolor neuropático aún no está clara. Esta revisión sistemática tuvo como objetivo evaluar su papel terapéutico potencial en el manejo del dolor neuropático. Métodos: Se realizó una revisión sistemática y metaanálisis de ensayos clínicos aleatorizados que compararon sulfato de magnesio (vía oral o intravenosa) con placebo u otros neuromoduladores en adultos con dolor neuropático. Se llevaron a cabo búsquedas en PubMed, EMBASE, Google Scholar y BVS-LILACS desde 1990 hasta mayo de 2023. El riesgo de sesgo se evaluó con la herramienta Cochrane Risk of Bias 2.0. Se calcularon diferencias de medias agrupadas (MD) con intervalos de confianza del 95% mediante un modelo de efectos aleatorios (método Mantel-Haenszel). La heterogeneidad se cuantificó con la estadística I2. Resultados: Se incluyeron siete ensayos con un total de 274 participantes. En comparación con placebo, el sulfato de magnesio mostró una reducción no significativa en las puntuaciones de dolor (MD: -1,13; IC 95%: -2,64 a 0,38), con heterogeneidad sustancial (P = 81%). Al compararlo con ketamina, un antagonista del receptor NMDA, el sulfato de magnesio también mostró una diferencia no significativa (MD: -0,67; IC 95%: -1,84 a 0,49), con heterogeneidad moderada (I2 = 62%). Conclusiones: El sulfato de magnesio podría tener potencial como opción terapéutica para el dolor neuropàtico; sin embargo, la evidencia actual es insuficiente para respaldar su uso rutinario. Se requieren estudios primarios bien diseñados para determinar su eficacia, las estrategias óptimas de dosificación y las indicaciones clínicas adecuadas.

-

Introduction

Neuropathic pain is a common condition, caused by damage to the central or peripheral nervous system due to various etiologies, such as infections, metabolic diseases (like type 2 diabetes mellitus), tumor invasion, exposure to chemicals, mechanical trauma, stroke, and spinal cord in- jury[1],[2]. The prevalence of chronic pain with a neuropathic component in the general population is estimated to range between 3 and 17%[3],[4]. Despite its high prevalence, the available therapeutic options are limited.

One of the objectives of neuropathic pain management is to modulate the activity of calcium channels, which is achieved by blocking the N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) re- ceptor[5]. This receptor plays a key role in central pain sensitization. Previous studies have demonstrated that NMDA receptor blockade, either through pharmacological agents like ketamine or through physiological mechanisms such as the use of magnesium sulfate, can be effective in the management of neuropathic pain[6],[7]. In the context of spinal surgery, intraoperative use of magnesium sulfate has been associated with a decrease in opioid consumption during and after surgery, leading to a reduction in the incidence of postoperative nausea and vomiting[4]. Additionally, magnesium sulfate has shown to be effective as an adjuvant in peripheral nerve blocks, suggesting its potential utility in the neuromodulation of neuropathic pain[6].

However, the role of magnesium sulfate in the specific management of neuropathic pain is not yet well-established. Therefore, this systematic review aims to evaluate the efficacy of magnesium sulfate in randomized clinical trials for the management of neuropathic pain, in order to answer the research question: in adults with neuropathic pain, does the use of magnesium sulfate compared to placebo or other neuromodulators, improve neuropathic pain scores?

-

Methods

-

Study design and registration

This systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials was conducted following the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and MetaAnalyses) guidelines[8]. The protocol for this review was prospectively registered in PROSPERO (International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews) under the registration number CRD42023441885.

-

Search strategy and information sources

A comprehensive search was conducted in the Medline database through PubMed, Google Scholar, EMBASE and BVS- LILACS from 1990 to May 2023, without language restrictions. The search terms used included variations of “Magnesium Sulfate”, “Neuropathic Pain”, and “Chronic Pain” as MeSH, Em- tree and DeCS terms (Supplementary Table S1). Additionally, a search for grey literature was performed in Open Grey, and a snowball search was conducted by reviewing the references of eligible studies.

-

Eligibility criteria

Randomized controlled trials were included if they met the following criteria: 1) adult patients aged 18 years or older with a diagnosis of neuropathic pain; 2) comparison of magnesium sulfate (intravenous or oral) versus placebo or other neuromodulators; 3) reporting of at least one of the outcomes of interest (pain scores, adverse events). Pilot studies, experimental studies, and those that used magnesium sulfate solely as an adjuvant and not as the primary therapy were excluded.

-

Study selection

Three independent reviewers conducted the study selection process in two phases. First, they screened the titles and abstracts to identify potentially eligible studies. Subsequently, they obtained the full-text articles of these studies and assessed their eligibility according to the established criteria. Any discrepancies were resolved through consensus or with the involvement of a fourth reviewer (FALA).

-

Data extraction

Three independent reviewers (FALA, GF, and JBC) extracted the following data: author, year of publication, sample size, clinical condition, intervention (dose and route of administration of magnesium sulfate), comparator, mean and standard deviation of pain scores, as well as the incidence of adverse events. No missing data was requested, as the included studies provided the necessary information. However, for the Felsby et al. study[9], the data from the figures was extracted using the WebPlotDigitizer tool[10]. These data were used to establish the mean and standard deviation of the Magnesium Sulfate, Ketamine, and Placebo groups[11]. The detailed process of extracting the data from the Felsby et al. figures using Web-PlotDigitizer has been published and is available at http://rpubs. com/fabrilasso/1180178.

-

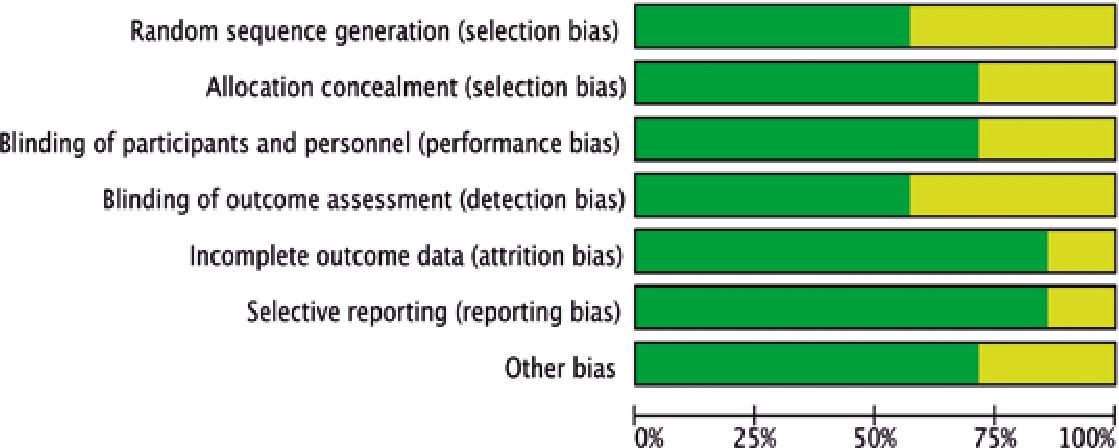

Assessment of methodological quality and risk of bias

The risk of bias in the included studies was evaluated using the Cochrane Risk of Bias 2.0 tool[12]. Three independent reviewers (FALA, GF, and JBC) assessed the risk of bias domains, and any discrepancies were resolved through consensus.

-

Endpoints

The outcomes of interest in this review were: 1) Reduction in neuropathic pain on the visual analog scale (0-10 cm); 2) Incidence of adverse events; 3) Dosages used for Magnesium Sulfate and the other neuromodulator. This comprehensive approach encompassed both efficacy and safety outcomes, allowing for a balanced assessment of the risk-benefit profile of magnesium sulfate in the management of neuropathic pain.

-

Data synthesis and analysis

The results from studies that reported neuropathic pain scores on a visual analog scale (0-10 cm) were pooled to estimate the mean difference (MD) with a 95% confidence interval, using random-effects models[14]. Heterogeneity was assessed using the I2 statistic considered significant if the p-value was less than 0.05, and was considered low when it was less than 25% and high when it exceeded 75%[15]. Additionally, a subgroup analysis will be performed comparing magnesium sulfate to other neuromodulators to further explore the differences in efficacy between these interventions.

-

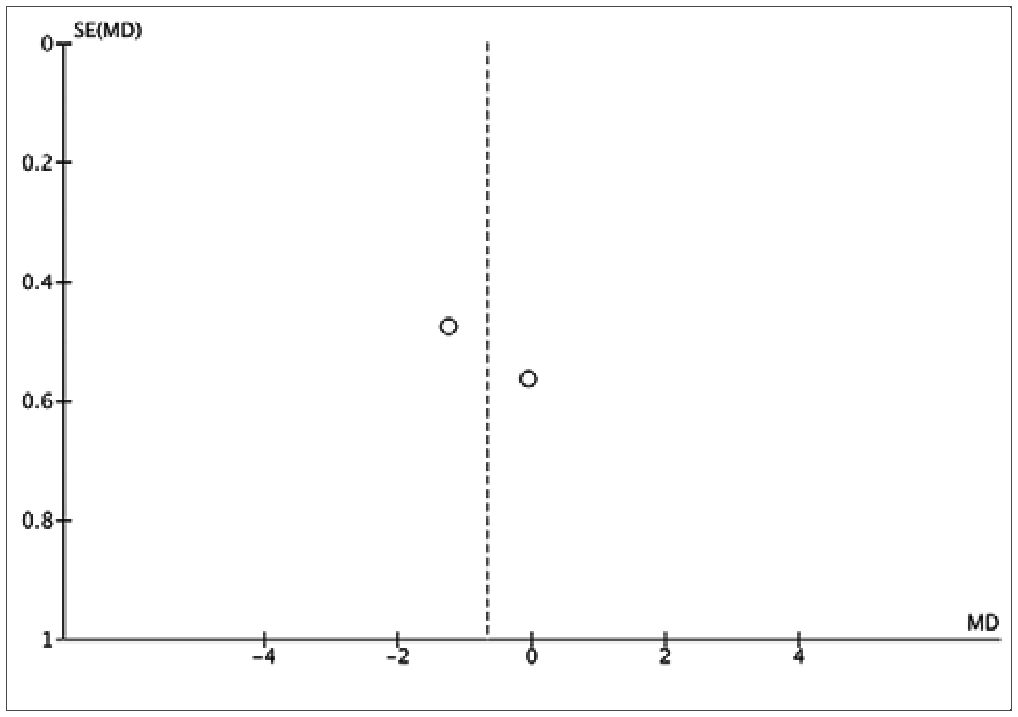

Sequential trial analysis

In addition to the conventional meta-analysis, a sequential trial analysis (TSA) was conducted to assess the reliability and conclusiveness of the results[16]. The TSA was performed using the TSA software (Copenhagen Trial Unit, Centre for Clinical Intervention Research, Copenhagen) with a significance level of 5% and a power of 80%. The required sample sizes and adjusted significance thresholds were calculated to determine whether the current results are conclusive or if additional studies are needed.

-

Assessment of reporting bias

Given that the number of studies included in the metaanalysis was less than 10, the Egger’s and Begg’s tests were not applied to detect publication bias, as these tests lack the necessary statistical power when working with a small data set[17]. Instead, a subjective evaluation of potential publication bias was carried out through visual inspection of the funnel plot. The graphical representation of the risk of bias assessment was generated using RevMan 5.4, developed by The Cochrane Collaboration.

-

Assessment of certainty of evidence

The certainty of evidence for the key outcomes was evaluated using the GRADE (Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation) system[18]. Four independent reviewers assessed the domains of risk of bias, inconsistency, indirectness, imprecision, and publication bias, and assigned an overall rating of very low, low, moderate, or high certainty. The final rating was determined by consensus.

-

Results

-

Study selection

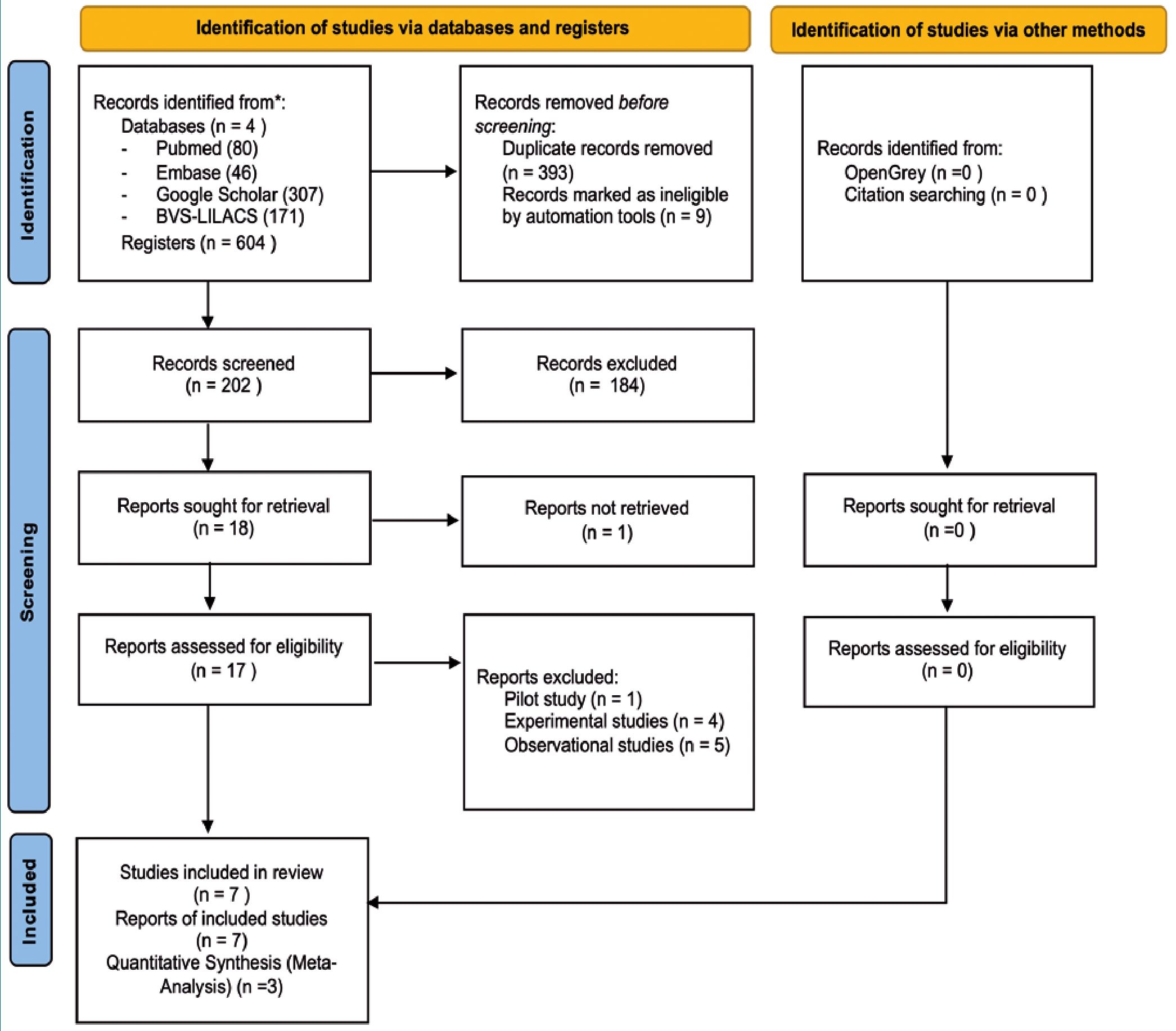

The initial search identified a total of 604 citations published between September 1990 and April 2023. Of these, 202 met the pre-established eligibility criteria, initiating the fulltext retrieval phase. Comprehensive searches were conducted across four key databases: PubMed contributed 80 citations, EMBASE 46 citations, and Google Scholar 307 citations, all of which were initially examined at the title and abstract level. Additionally, with the aim of mitigating potential publication bias, a search was carried out in the BVS-LILACS database, which identified 171 citations in Spanish.

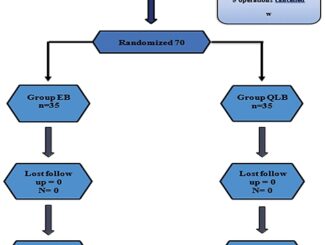

In total, 604 citations were compiled in the initial search. After a process of duplicate removal by the authors, and the application of the pre-defined exclusion criteria by three independent reviewers, 17 full-text records were obtained for evaluation. Ultimately, 7 studies were included in the qualitative systematic review, and 3 in the quantitative synthesis (Figure 1).

-

Study characteristics

This systematic review considered 7 studies encompassing 274 patients, published between 1995 and 2023. The sample sizes of the included trials ranged from n = 7 to n = 87 patients, with a mean age spanning 46.6 to 76 years. All selected studies employed a randomized design for the allocation of patients to the various treatment groups. In the majority of cases (6 out of 7 trials), clear descriptions of the blinding implementation were reported.

The administration of magnesium sulfate was the primary focus in these trials, with the majority opting for a bolus injection strategy followed by continuous infusion. The bolus doses ranged from 30 mg/kg to 80 mg/kg, or single doses between 1 and 3 grams. Two of the studies utilized oral administration of magnesium sulfate, with doses of 400 mg of magnesium oxide and 100 mg of magnesium gluconate given twice dai- ly[19],[20]. The duration and frequency of dosing also varied, encompassing single doses up to repeated doses over a period of up to 28 days. After the interventions, the mean pain scores in the magnesium sulfate groups ranged from 3.1 to 4.7, while the placebo groups had mean scores between 4.0 and 7.2. The Table 1 provides a summary of the included studies and their results.

-

Excluded studies

Of the 18 studies reviewed in full-text, 10 were excluded. The excluded studies and the reasons for their exclusion can be found in Supplementary Table S2.

Figure 1. PRISMA.

-

Efficacy outcomes

-

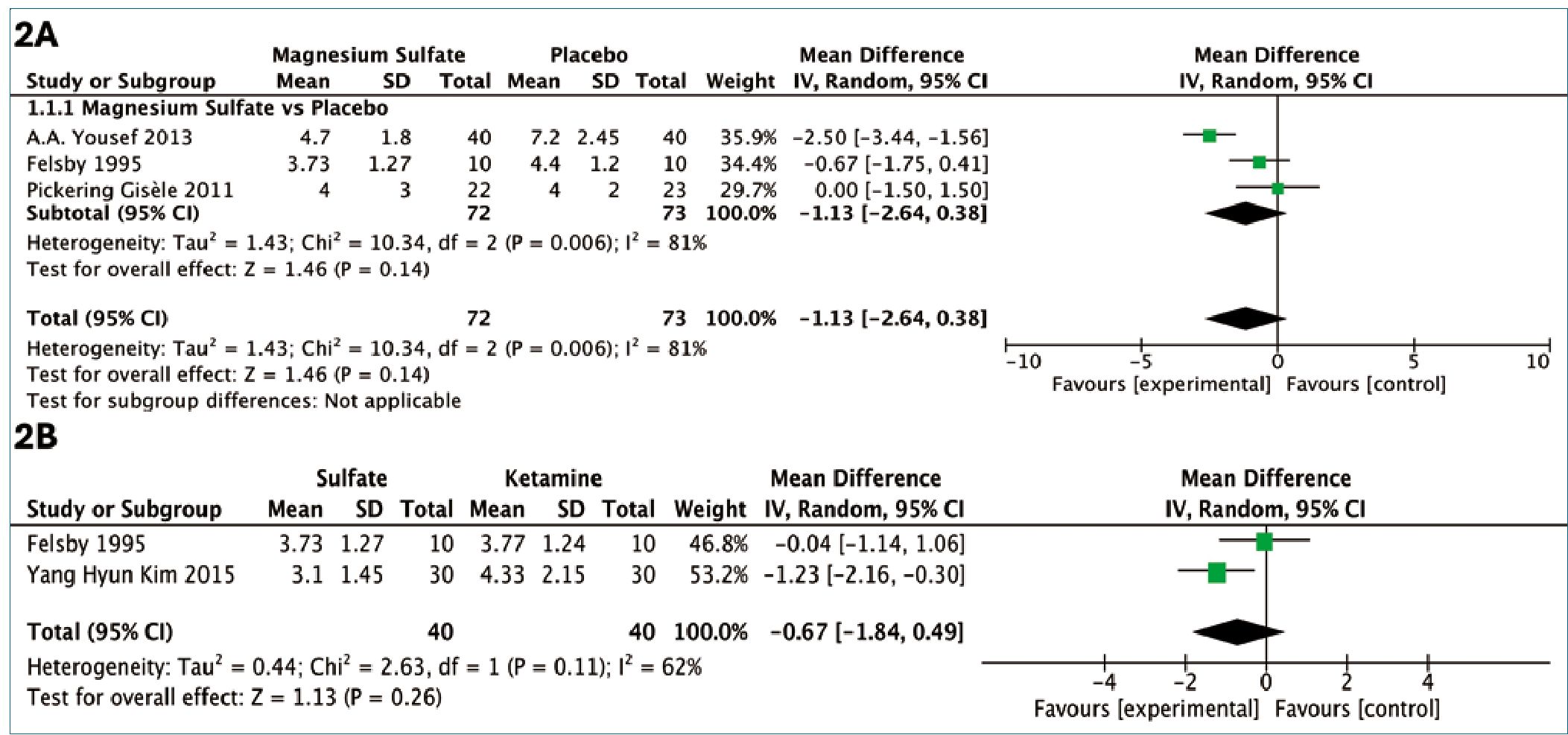

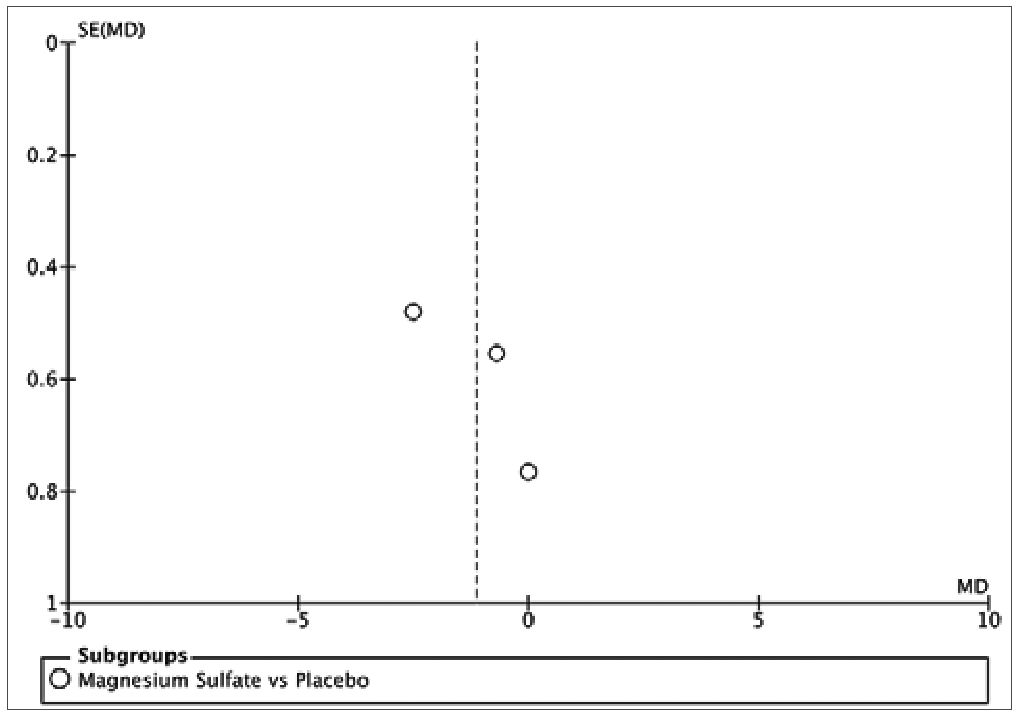

Magnesium sulfate versus placebo

The pooled analysis of the studies comparing magnesium sulfate to placebo revealed a non-significant mean difference (MD) of -1.13 (95% CI: -2.64, 0.38) in neuropathic pain scores (Figure 2A). Although not statistically significant, the effect estimate showed considerable uncertainty and high heterogeneity, limiting conclusions about the efficacy of magnesium sulfate compared to placebo. The high degree of heterogeneity observed across the included studies, with an I2 value of 81%. This variability in the reported effects may be attributed to the differences in the clinical contexts evaluated. Felsby et al.[9] examined magnesium sulfate versus placebo in patients with diverse etiologies of neuropathic pain, while Yousef et al.[19] focused on patients with chronic low back pain of neuropathic origin. Additionally, Pickering Gisèle et al.[20] specifically assessed the oral administration of magnesium sulfate.

-

Magnesium sulfate versus ketamine

This systematic review also explored the comparative efficacy of magnesium sulfate and the neuromodulator ketamine, which acts on the same NMDA receptor. The quantitative analysis of the studies by Kim et al.[22] and Felsby et al.[9] revealed a decrease in the mean difference, although it did not reach statistical significance. Specifically, the pooled mean difference between magnesium sulfate and ketamine was -0.67 (95% CI: -1.84, 0.49), with a moderate degree of heterogeneity (I2 = 62%), and no statistically significant difference between the groups (Figure 2B). This variability in the treatment effects may be attributed to the differences in the clinical contexts evaluated. While Felsby et al.[9] assessed the efficacy of magnesium sulfate across various neuropathic pain etiologies, Kim et al.[22] focused specifically on the use of magnesium sulfate in patients with neuropathic pain due to post-herpetic neuralgia. These disparities in the study populations and underlying pain conditions could contribute to the observed heterogeneity.

-

Safety outcomes

The studies indicated few adverse effects associated with the administration of Magnesium Sulfate, including drowsiness, a sense of overwhelming confusion, warmth, pain at the injection site, and sedation. No major adverse effects were reported, and these minor side effects were only noted in two studies (n = 54)[9],[22]. No statistically significant differences were found in adverse effects in clinical trials when magnesium sulfate was used.

Table 1. Characteristics of the included studies

| Clinical Condition Author and Year | Patients | Magnesium Control | Pain Outcomes (VAS) | Adverse Effects | |

| Intervention | Intervention | ||||

| Chronic S. Brill 2002(21)Postherpetic

Neuralgia |

n = 7 | Infusion of 30 mg/kg over 30 minutes | Normal saline solution 0.9% | Baseline: Mean 6.7 ± 1.7 Post: Mean 1.9 ± 3.2 | None reported |

| Chronic A.A. Yousef Neuropathic Back 2013(19) Pain | n = 80 | Infusion 1 g/4h for 2 weeks + capsules (400 mg oxide + 100 mg gluconate) 2x/day for 4 weeks | Normal saline 0.9% + placebo capsules | Baseline: Mean 7.4 ± 2.4 2 weeks: 3.4 ± 1.15 6 weeks: 3.9 ± 1.4 3 months: 4.4 ± 1.6 6 months: 4.7 ± 1.8 | None reported |

| Postherpetic Yang Hyun Kim | n = 30 | 30 mg/kg in 3 sessions | Ketamine 1 mg/kg | Baseline: Mean 7.7 ± | Drowsiness and |

| Neuralgia 2015(22) | every 2 days | in 3 sessions every2 days | 1.55 Post 2 weeks:Mean 3.1 ± 1.45 | dizziness | |

| Neuropathic Pain Felsby 1995(9)Various Causes | n = 10 | Bolus 80 mg/kg over 10 min + continuous infusion 80 mg/kg/h for 1 hour | Bolus 0.2 mg/kg + infusion 0.3 mg/ kg/h | Baseline: 4.66 ± 1.53 With Magnesium: 3.73 ± 1.27 With Placebo: 4.4 ± 1.20 With Ketamine: 3.77 ± 1.24 | Warmth, injection pain, sedation |

| Postoperative M.E. HassanNeuropathic Pain 2023(23) | n = 87 | Ketamine 0.5 mg/ kg induction + 0.12 mg/kg/h for 24h + Magnesium 50 mg/kg | Ketamine 0.5 mg/ kg induction + saline solution | Chronic pain incidence: Ketamine: 20.5% Ketamine + Magnesium sulfate: 16.3% | Not reported |

| Persistent Gisele Pickering Neuropathic Pain 2020 (24) | n = 60 | 3 g Magnesium + 0.5 mg/kg Ketamine vs. 0.5 mg/kg Ketamine | Normal saline vs. normal saline + normal saline | Placebo (mean AUC ± SD) 187 ± 90; Ketamine (mean AUC ± SD) 185 ± 100; Ketamine + Magnesium sulfate (mean AUC ± SD) 196 ± 92 | Not reported |

| Postoperative, Pickering GisèlePost-Traumatic, 201 1 (25) and Post-Herpetic

Neuropathic Pain |

n = 45 | Magnesium chloride trihydrate (419 Mg) capsule every 6 hours for 28 days | Placebo (lactose capsule) every 6 hours | Magnesium n = 22: Baseline (mean ± SD) 5 ± 3 (Range: 0-10), Final (28 days) mean 4 ± 3 (Range: 0-9), p < 0.0001Placebo n = 23: Baseline (mean ± SD) 5 ± 3 (Range: 0-10), Final (mean) 4 ± 2 (Range: 0-9), p < 0.0001 | Not reported |

| AUC: area under the curve; VAS: Visual Analog Scale. Used to measure pain intensity; mg/kg: milligrams per kilogram, a dosage measurement based on the patient’s weight; h: hour; g: gram; %: percentage; n: number of participants in the study. Baseline: Initial value measured before treatment; Post: Value measured after treatment; +: Indicates a combination of treatments in the intervention group; vs: versus, used to denote comparison between two treatment groups. | |||||

-

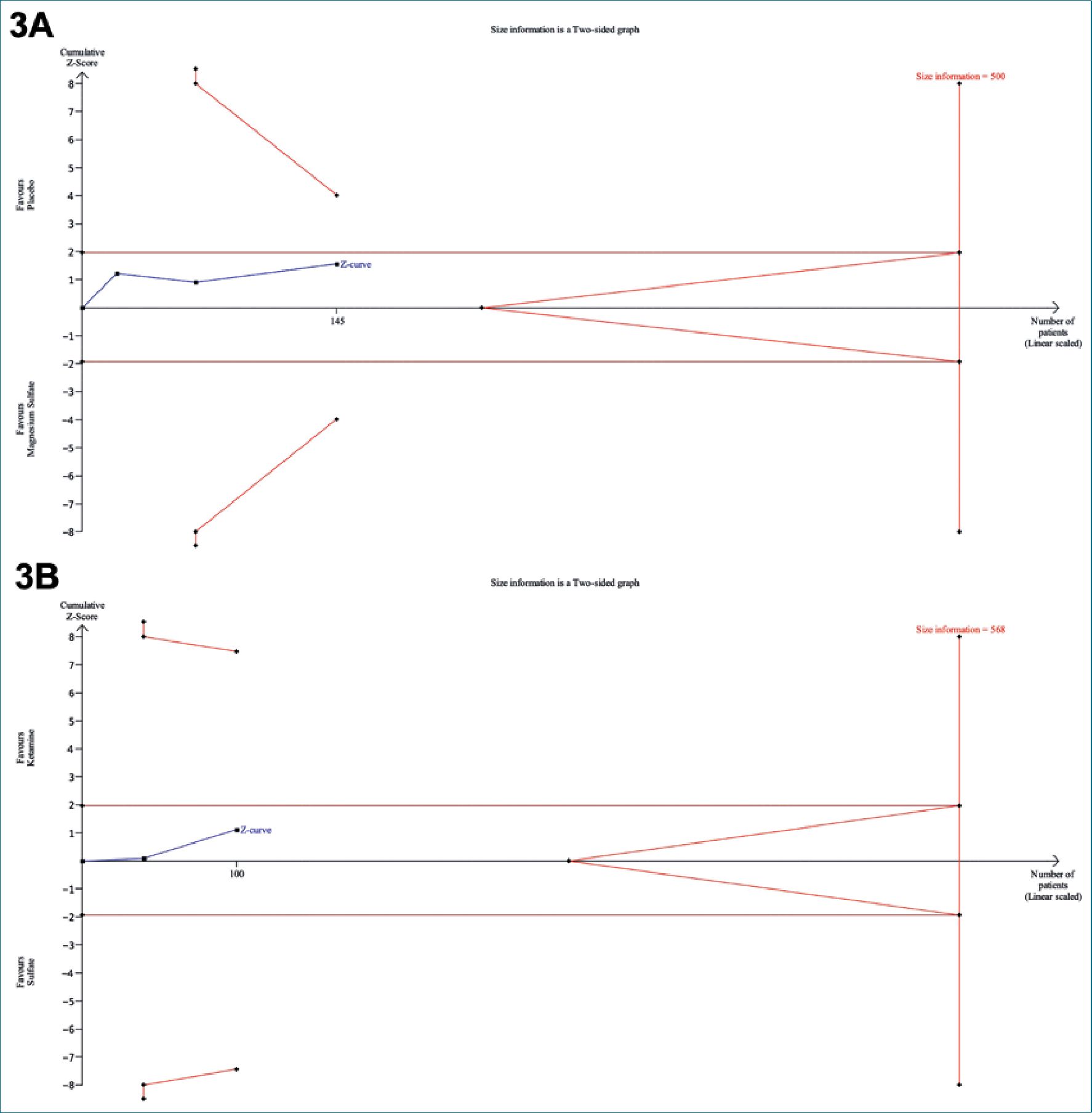

Sequential trial analysis

The Sequential Trial Analysis (TSA) evaluated the mean difference in pain scores measured on the Visual Analog Scale (VAS) between the use of magnesium sulfate and the control (Placebo/Ketamine) (Figure 3). The plot shows a blue line representing the cumulative mean difference in pain scores across

Figure 2. A: Comparative Mean Pain Scores on a 0-10 cm Visual Analog Scale for Magnesium Sulfate Versus Placebo; B: Magnesium Sulfate vs. Ketamine for Neuropathic Pain: Reduction in Mean Scores on the Visual Analog Pain Scale.

the included studies. This blue line does not cross the established statistical significance boundaries nor the adjusted lines, the cumulative evidence remains inconclusive due to insufficient sample size and lack of statistical significance within the 95% confidence interval and with 80% power[26]. It is important to consider the variability observed in the results, as well as the relatively small size of the included studies. These factors indicate the need for further research to validate the observed findings and confirm the magnitude of the effect of magnesium sulfate in the management of neuropathic pain more conclusively.

-

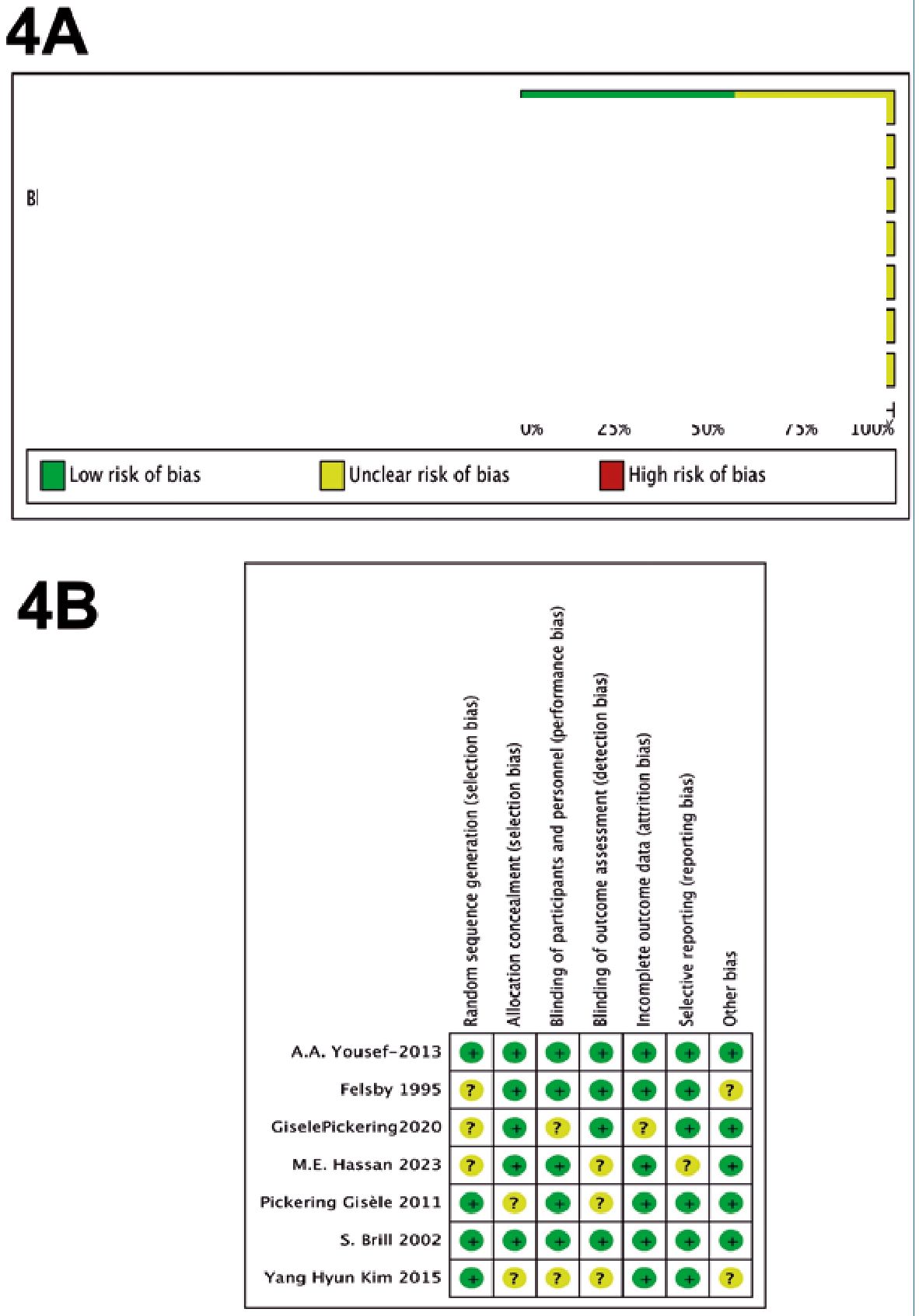

Risk of bias in studies

The assessment of bias risk in the studies included in this analysis indicated a low level of potential biases (Figure 4). The three studies selected for quantitative synthesis were deemed to have a “low” risk of bias according to the Cochrane tool. The funnel plot showed no asymmetry, suggesting the absence of small-study effects. However, given the limited number of studies, definitive conclusions regarding publication bias cannot be drawn. It is important to note that the possibility of publication bias cannot be entirely ruled out in the context of this study.

-

Quality assessment

According to the GRADE system, the certainty of evidence was rated as “Moderate” for the use of magnesium sulfate versus placebo, and “Low” for the comparison with ketamine (Table 2). This classification is primarily due to the limited number of patients and the variability in the clinical contexts of the studies, which may have caused substantial heterogeneity in the results. The high degree of heterogeneity observed in the magnesium sulfate versus placebo comparison, with an I2 value of 81%, further contributes to the uncertainty surrounding the pooled estimates. Similarly, the comparison between magnesium sulfate and ketamine showed moderate heterogeneity, with an I2 of 62%, which may also limit the interpretability of these findings. Given the limited number of studies and the substantial heterogeneity observed, especially in comparisons with placebo and ketamine, no definitive conclusions can be drawn regarding the clinical efficacy of magnesium sulfate in neuropathic pain. Well-designed, larger-scale randomized controlled trials are needed to clarify its potential role and establish its place within the therapeutic strategies for neuropathic pain.

-

Discussion

Neuropathic pain, characterized by an alteration in the pain signaling pathways of the central and peripheral nervous system, is a clinical challenge that requires innovative therapeutic approaches[27]. Magnesium sulfate, with its unique pharmacodynamic properties, has garnered interest as a potentially promising option in this area[28].

The mechanisms of action of magnesium sulfate, which include the blockade of calcium entry and antagonism of the N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptor channels, provide a plausible explanation for its potential efficacy in relieving neuropathic pain[29],[30]. These mechanisms intervene in the modulation of pain transmission and the inhibition of neuronal excitability, which could influence the perception and intensity of neuropathic pain[31],[32]. The NMDA receptor plays a key role in the central sensitization of neuropathic pain. Its activation contributes to the hyperexcitability of dorsal horn neurons, resulting in increased perception and amplification of the painful stimulus[33],[34]. By blocking this receptor, magnesium sulfate can attenuate such hyperexcitability, thereby reducing nocicep tive transmission and, consequently, neuropathic pain[35],[36].

Figure 3. Sequential Trial Analysis 3A: Magnesium Sulfate vs. Placebo; 3B: Magnesium Sulfate vs. Ketamine.

Table 2. Evidence Certainty Assessment System

| Outcome n of participants (studies) | Relative effect (95% CI) | Mean Difference (MD) | Certainty | ¿What happens? |

| Magnesium Sulfate vs PlaceboVAS: 0 a 10 cm n = 145 (3 RCTs) | – 2.64, 0.38 | MD 1.13 less VAS (2.64 less to 0.38 more) | OOOOLow | The use of magnesium sulfate could be important in reducing pain scores in patients with neuropathic pain, although further research is required to confirm these findings |

| Magnesium Sulfate vs KetamineVAS: 0 a 10 cm n = 80 (2 RCTs) | -1.84, 0.49 | MD 0.67 less VAS (1.84 lower to 0.49 higher) | OOOOVery Low | The use of magnesium sulfate could be important in reducing pain scores in patients with neuropathic pain, although further research is required to confirm these findings |

Figure 4. Risk of Bias Assessment Framework. A: Cumulative; B: Individual.

The results of this review showed a reduction in pain measured on the visual analog scale with the use of magnesium sulfate compared to placebo, with a mean difference (MD) of -1.13 (95% CI: -2.64, 0.38), although this difference did not reach statistical significance and had high heterogeneity with an I2 of 81%. This variability may be due to differences in clinical context, dosage regimens, and routes of administration across studies. Moreover, pain was assessed in diverse neuropathic conditions, including postherpetic neuralgia, postoperative pain, and chronic neuropathic pain, further contributing to outcome variability. Profound differences in magnesium sulfate administration, ranging from single infusions to long-term oral regimens, also limit the ability to draw uniform conclusions. The lack of statistical significance may be partly explained by the small sample sizes in several included trials, reducing statistical power.

Neuropathic pain represents a significant clinical challenge due to the limited efficacy of available treatments[37],[38]. Despite advances in the understanding of the underlying pathophysiological mechanisms, many patients with neuropathic pain continue to experience persistent and debilitating symptoms, even with optimal treatment[39]. In this context, the identification of new therapeutic strategies that can more effectively address the various aspects of neuropathic pain becomes cru- cial[40].

Additionally, this systematic review explored the action on the NMDA receptor, a mechanism of action shared by Ketamine and Magnesium Sulfate. The quantitative analysis revealed a decrease, although it did not reach statistical significance, with a mean difference (MD) of -0.67 (95% CI: -1.84, 0.49) and moderate heterogeneity (I2: 62%). This finding is particularly notable given the well-established efficacy of ketamine in the management of neuropathic pain. Ketamine has been demonstrated to be an effective intervention for neuropathic pain, with a pooled risk ratio of 1.59 (95% CI: 1.32-1.92) for achieving clinically meaningful pain relief compared to placebo[41]. Additionally, the number needed to treat (NNT) for ketamine to provide one additional patient with at least 50% pain relief has been estimated to be as low as 4[42].

The decrease observed in the mean difference between magnesium sulfate and ketamine did not reach statistical significance, which limits the strength of any conclusion regarding its comparative efficacy. While both agents act on the NMDA receptor, the robust evidence supporting ketamine’s effectiveness in neuropathic pain contrasts with the more uncertain role of magnesium sulfate. Further research is needed to determine whether magnesium sulfate can serve as a complementary or alternative option in specific clinical scenarios, particularly when ketamine is contraindicated, poorly tolerated, or when a multimodal analgesic strategy is being considered.

This systematic review has several methodological limitations that must be acknowledged. First, the search strategy did not include clinical trial registries, which may have limited the ability to assess publication bias. Although no clear evidence of bias was detected, the omission of these sources prevents ruling it out entirely. Second, the number of studies included in the quantitative synthesis was small, and sample sizes were generally limited, which reduces the statistical power and precision of the pooled estimates. Moreover, substantial heterogeneity was observed among the included studies (I up to 81%), complicating the extrapolation of findings to specific clinical settings. Finally, the overall quality of the evidence was rated as Low according to the GRADE approach, underscoring the need for cautious interpretation of the results.

Future research should focus on addressing these limitations. Larger, more robust clinical trials are needed to evaluate the effect of magnesium sulfate in specific clinical contexts, such as postoperative, post-herpetic, or other well-defined neuropathic pain etiologies. These future studies should also explore different dosing regimens of magnesium sulfate to determine the optimal posology for the management of neuropathic pain.

-

Conclusion

Magnesium sulfate may hold potential as a therapeutic option for neuropathic pain; however, current evidence is insufficient to support its routine use. Further well-designed primary studies are needed to determine its efficacy, optimal dosing strategies, and appropriate clinical indications.

Acknowledgments: The first author, Fabricio Lasso, wishes to express his deepest gratitude to his mother, Olivia Andrade Acosta, for her unwavering support, love, and encouragement throughout this journey. He also dedicates this work in loving memory of his grandmother, Carmela Acosta, whose enduring strength and values continue to inspire him from above.

PROSPERO registration: CRD42023441885

-

References

1. Costigan M, Scholz J, Woolf CJ. Neuropathic pain: a maladaptive response of the nervous system to damage. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2009;32(1):1–32. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.neuro.051508.135531 PMID:19400724

2. van Hecke O, Austin SK, Khan RA, Smith BH, Torrance N. Neuropathic pain in the general population: a systematic review of epidemiological studies. Pain. abril de 2014;155(4):654-62. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pain.2013.11.013.

3. Petrenko AB, Yamakura T, Baba H, Shimoji K. The role of N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptors in pain: a review. Anesth Analg. octubre de 2003;97(4):1108-16.

4. Yue L, Lin ZM, Mu GZ, Sun HL. Impact of intraoperative intravenous magnesium on spine surgery: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. EClinicalMedicine. enero de 2022;43:101246.

5. Chen C, Tao R. The Impact of Magnesium Sulfate on Pain Control After Laparoscopic Cholecystectomy: A Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Studies. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. diciembre de 2018;28(6):349-53. https://doi.org/10.1097/SLE.0000000000000571.

6. Zeng J, Chen Q, Yu C, Zhou J, Yang B. The Use of Magnesium Sulfate and Peripheral Nerve Blocks: An Updated Meta-analysis and Systematic Review. Clin J Pain. 1 de agosto de 2021;37(8):629-37.

7. Guimarães Pereira JE, Ferreira Gomes Pereira L, Mercante Linhares R, Darcy Alves Bersot C, Aslanidis T, Ashmawi HA. Efficacy and Safety of Ketamine in the Treatment of Neuropathic Pain: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. J Pain Res. 2022 Apr;15:1011–37. https://doi.org/10.2147/JPR.S358070 PMID:35431578

8. Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 29 de marzo de 2021;372:n71.

9. Felsby S, Nielsen J, Arendt-Nielsen L, Jensen TS. NMDA receptor blockade in chronic neuropathic pain: a comparison of ketamine and magnesium chloride. Pain. febrero de 1996;64(2):283-91. https://doi.org/10.1016/0304-3959(95)00113-1.

10. Drevon D, Fursa SR, Malcolm AL. Intercoder Reliability and Validity of WebPlotDigitizer in Extracting Graphed Data. Behav Modif. marzo de 2017;41(2):323-39. https://doi.org/10.1177/0145445516673998.

11. Wan X, Wang W, Liu J, Tong T. Estimating the sample mean and standard deviation from the sample size, median, range and/or interquartile range. BMC Medical Research Methodology. 19 de diciembre de 2014;14(1):135.

12. Sterne JAC, Savović J, Page MJ, Elbers RG, Blencowe NS, Boutron I, et al. RoB 2: a revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ. 28 de agosto de 2019;366:l4898.

13. Jadad AR, Moore RA, Carroll D, Jenkinson C, Reynolds DJ, Gavaghan DJ, et al. Assessing the quality of reports of randomized clinical trials: is blinding necessary? Control Clin Trials. febrero de 1996;17(1):1-12. https://doi.org/10.1016/0197-2456(95)00134-4.

14. Dworkin RH, Turk DC, Wyrwich KW, Beaton D, Cleeland CS, Farrar JT, et al. Interpreting the clinical importance of treatment outcomes in chronic pain clinical trials: IMMPACT recommendations. J Pain. febrero de 2008;9(2):105-21.

15. Higgins JPT, Thompson SG. Quantifying heterogeneity in a meta-analysis. Stat Med. 15 de junio de 2002;21(11):1539-58. https://doi.org/10.1002/sim.1186.

16. Wetterslev J, Thorlund K, Brok J, Gluud C. Trial sequential analysis may establish when firm evidence is reached in cumulative meta-analysis. J Clin Epidemiol. enero de 2008;61(1):64-75.

17. Egger M, Smith GD, Schneider M, Minder C. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ. 13 de septiembre de 1997;315(7109):629-34. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.315.7109.629.

18. Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Vist GE, Kunz R, Falck-Ytter Y, Alonso-Coello P, et al. GRADE: an emerging consensus on rating quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. BMJ. 24 de abril de 2008;336(7650):924-6. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.39489.470347.AD.

19. Yousef AA, Al-deeb AE. A double-blinded randomised controlled study of the value of sequential intravenous and oral magnesium therapy in patients with chronic low back pain with a neuropathic component. Anaesthesia. marzo de 2013;68(3):260-6. https://doi.org/10.1111/anae.12107.

20. Pickering G, Morel V, Simen E, Cardot JM, Moustafa F, Delage N, et al. Oral magnesium treatment in patients with neuropathic pain: a randomized clinical trial. Magnes Res. junio de 2011;24(2):28-35. https://doi.org/10.1684/mrh.2011.0282.

21. Brill S, Sedgwick PM, Hamann W, Di Vadi PP. Efficacy of intravenous magnesium in neuropathic pain. Br J Anaesth. noviembre de 2002;89(5):711-4. https://doi.org/10.1093/bja/89.5.711.

22. Kim YH, Lee PB, Oh TK. Is magnesium sulfate effective for pain in chronic postherpetic neuralgia patients comparing with ketamine infusion therapy? J Clin Anesth. junio de 2015;27(4):296-300.

23. Hassan ME, Mahran E. Effect of magnesium sulfate with ketamine infusions on intraoperative and postoperative analgesia in cancer breast surgeries: a randomized double-blind trial. Braz J Anesthesiol. 2023;73(2):165–70. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bjane.2021.07.015 PMID:34332956

24. Pickering G, Pereira B, Morel V, Corriger A, Giron F, Marcaillou F, et al. Ketamine and Magnesium for Refractory Neuropathic Pain: A Randomized, Double-blind, Crossover Trial. Anesthesiology. julio de 2020;133(1):154-64.

25. Pickering G, Morel V, Simen E, Cardot JM, Moustafa F, Delage N, et al. Oral magnesium treatment in patients with neuropathic pain: a randomized clinical trial. Magnes Res. junio de 2011;24(2):28-35. https://doi.org/10.1684/mrh.2011.0282.

26. Brok J, Thorlund K, Gluud C, Wetterslev J. Trial sequential analysis reveals insufficient information size and potentially false positive results in many meta-analyses. J Clin Epidemiol. agosto de 2008;61(8):763-9.

27. Costigan M, Scholz J, Woolf CJ. Neuropathic pain: a maladaptive response of the nervous system to damage. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2009;32(1):1–32. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.neuro.051508.135531 PMID:19400724

28. Shin HJ, Na HS, Do SH. Magnesium and Pain. Nutrients. 23 de julio de 2020;12(8):2184. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu12082184.

29. Feria M, Abad F, Sánchez A, Abreu P. Magnesium sulphate injected subcutaneously suppresses autotomy in peripherally deafferented rats. Pain. junio de 1993;53(3):287-93. https://doi.org/10.1016/0304-3959(93)90225-E.

30. Petrenko AB, Yamakura T, Baba H, Shimoji K. The role of N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptors in pain: a review. Anesth Analg. octubre de 2003;97(4):1108-16.

31. Mao J, Price DD, Hayes RL, Lu J, Mayer DJ, Frenk H. Intrathecal treatment with dextrorphan or ketamine potently reduces pain-related behaviors in a rat model of peripheral mononeuropathy. Brain Res. 5 de marzo de 1993;605(1):164-8. https://doi.org/10.1016/0006-8993(93)91368-3.

32. Woolf CJ, Thompson SWN. The induction and maintenance of central sensitization is dependent on N-methyl-D-aspartic acid receptor activation; implications for the treatment of post-injury pain hypersensitivity states. Pain. marzo de 1991;44(3):293-9.

33. Kuner R. Central mechanisms of pathological pain. Nat Med. noviembre de 2010;16(11):1258-66. https://doi.org/10.1038/nm.2231.

34. Latremoliere A, Woolf CJ. Central sensitization: a generator of pain hypersensitivity by central neural plasticity. J Pain. septiembre de 2009;10(9):895-926.

35. Srebro D, Vuckovic S, Milovanovic A, Kosutic J, Vujovic KS, Prostran M. Magnesium in Pain Research: state of the Art. Curr Med Chem. 2017;24(4):424–34. https://doi.org/10.2174/0929867323666161213101744 PMID:27978803

36. Begon S, Pickering G, Eschalier A, Dubray C. Magnesium and MK-801 have a similar effect in two experimental models of neuropathic pain. Brain Res. 29 de diciembre de 2000;887(2):436-9.

37. van Hecke O, Austin SK, Khan RA, Smith BH, Torrance N. Neuropathic pain in the general population: a systematic review of epidemiological studies. Pain. abril de 2014;155(4):654-62. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pain.2013.11.013.

38. Finnerup NB, Attal N, Haroutounian S, McNicol E, Baron R, Dworkin RH, et al. Pharmacotherapy for neuropathic pain in adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Neurol. febrero de 2015;14(2):162-73.

39. Costigan M, Scholz J, Woolf CJ. Neuropathic pain: a maladaptive response of the nervous system to damage. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2009;32(1):1–32. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.neuro.051508.135531 PMID:19400724

40. Colloca L, Ludman T, Bouhassira D, Baron R, Dickenson AH, Yarnitsky D, et al. Neuropathic pain. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 16 de febrero de 2017;3:17002. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrdp.2017.2.

41. Guimarães Pereira JE, Ferreira Gomes Pereira L, Mercante Linhares R, Darcy Alves Bersot C, Aslanidis T, Ashmawi HA. Efficacy and Safety of Ketamine in the Treatment of Neuropathic Pain: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. J Pain Res. 2022 Apr;15:1011–37. https://doi.org/10.2147/JPR.S358070 PMID:35431578

42. Brinck EC, Tiippana E, Heesen M, Bell RF, Straube S, Moore RA, et al. Perioperative intravenous ketamine for acute postoperative pain in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 20 de diciembre de 2018;12(12):CD012033. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD012033.pub4.

-

Supplementary

| Table S1. Search Strategy and Results | ||

| Source | Search Terms | Search Results |

| Pubmed | (Magnesium Sulfate) AND ((Pain Neuropathic) OR (Chronic Pain)) | 80 |

| Embase | Sulfate AND magnesium AND chronic AND pain AND (‘article’/it OR ‘article in press’/it) AND ‘chronic pain’/dm | 46 |

| Google Scholar | Magnesium Sulfate “Pain Neuropathic” | 307 |

| BVS-LILACS | (Sulfato de Magnesio) AND (Dolor Cronico) | 171 |

| Total | 604 | |

| Table S2. Characteristics of excluded studies | ||

| Study | Reason for Exclusion | Reference |

| Vincent Crosby 2000 | Pilot study | (1) |

| Maizels 2004 | Magnesium use in migraine | (2) |

| Song 2011 | Does not meet the inclusion criteria for chronic neuropathic pain | (3) |

| Lee 2012 | Does not meet the inclusion criteria for chronic neuropathic pain | (4) |

| Gaul 2015 | Does not meet the inclusion criteria for neuropathic pain | (5) |

| Baaklini 2015 | Experimental study in rats, inclusion of cancer patients without neuropathic pain | (6) |

| Kanta Kido 2020 | Experimental study in rats | (7) |

| Tak Kyu Oh 2019 | Observational study | (8) |

| Delage 2017 | Study not completed | (9) |

| Ioannis Chronakis 2021 | Full text not accessible, only conference abstract | (10) |

Figure S1. Funnel Plot of the studies comparing Magnesium Sulfate and placebo.

Figure S2. Funnel Plot of studies comparing Ketamine vs Magnesium Sulfate.

Conflicts of interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

-

References

- 1. Crosby V, Wilcock A, Mrcp D, Corcoran R. The Safety and Efficacy of a Single Dose (500 mg or 1 g) of Intravenous Magnesium Sulfate in Neuropathic Pain Poorly Responsive to Strong Opioid Analgesics in Patients with Cancer. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management. 1 de enero de 2000;19(1):35-9.

- 2. Maizels M, Blumenfeld A, Burchette R. A combination of riboflavin, magnesium, and feverfew for migraine prophylaxis: a randomized trial. Headache. octubre de 2004;44(9):885-90. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1526-4610.2004.04170.x

- 3. Song JW, Lee YW, Yoon KB, Park SJ, Shim YH. Magnesium sulfate prevents remifentanil-induced postoperative hyperalgesia in patients undergoing thyroidectomy. Anesth Analg. agosto de 2011;113(2):390-7. https://doi.org/10.1213/ANE.0b013e31821d72bc

- 4. Lee AR, Yi H won, Chung IS, Ko JS, Ahn HJ, Gwak MS, et al. Magnesium added to bupivacaine prolongs the duration of analgesia after interscalene nerve block. Can J Anaesth. enero de 2012;59(1):21-7.

- 5. Gaul C, Diener HC, Danesch U; Migravent® Study Group. Improvement of migraine symptoms with a proprietary supplement containing riboflavin, magnesium and Q10: a randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind, multicenter trial. J Headache Pain. 2015;

- 6. Gaul C, Diener HC, Danesch U; Migravent® Study Group. Improvement of migraine symptoms with a proprietary supplement containing riboflavin, magnesium and Q10: a randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind, multicenter trial. J Headache Pain. 2015;16(1):516. https://doi.org/10.1186/s10194-015-0516-6

- 7. Baaklini LG, Arruda GV, Sakata RK. Assessment of the Analgesic Effect of Magnesium and Morphine in Combination in Patients With Cancer Pain: A Comparative Randomized Double-Blind Study. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. mayo de 2017;34(4):353-7. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049909115621895..

- 8. Kido K, Katagiri N, Kawana H, Sugino S, Konno D, Suzuki J, et al. Effects of magnesium sulfate administration in attenuating chronic postsurgical pain in rats. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1 de enero de 2021;534:395-400. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbrc.2020.11.069

- 9. Oh TK, Chung SH, Park J, Shin H, Chang CB, Kim TK, et al. Effects of Perioperative Magnesium Sulfate Administration on Postoperative Chronic Knee Pain in Patients Undergoing Total Knee Arthroplasty: A Retrospective Evaluation. J Clin Med. 17 de diciembre de 2019;8(12):2231.

- 10. Delage N, Morel V, Picard P, Marcaillou F, Pereira B, Pickering G. Effect of ketamine combined with magnesium sulfate in neuropathic pain patients (KETAPAIN): study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials. 3 de noviembre de 2017;18(1):517.

- 11. Chronakis I, Chainaki E, Polaki N, Siafaka I, Vadalouka A. Efficacy of iv infusion of magnesium sulphate and dromperidol on the management of neuropathic and somatosensory chronic pain – a two pain center study. Signa Vitae-Journal of Anesthesiology, Intensive Care Journal, Emergency Medical Journal. 15 de septiembre de 2021;17(S1):12-12.

ORCID

ORCID