Ramy Mahrose MD.1, Menna-allah Gamal Abd-elaty Mohamed M.B.,B.CH2*, Ahmed Saoudy Abdelghafour Mohamed MD.3, Wael Sayed Ahmed Abdelghaffar Algarabawy MD4

Recibido: 16-04-2025

Aceptado: 29-04-2025

©2025 El(los) Autor(es) – Esta publicación es Órgano oficial de la Sociedad de Anestesiología de Chile

Revista Chilena de Anestesia Vol. 54 Núm. 6 pp. 851-857|https://doi.org/10.25237/revchilanestv54n6-10

PDF|ePub|RIS

Oxigenación con cánula nasal de alto flujo versus oxigenación estándar para endoscopia gastrointestinal con sedación en pacientes obesos

Abstract

Background: During the GIE procedure performed under sedation, various complications can occur, with hypoxia being the most frequent, significantly impacting mortality and morbidity. Methodology: A total of 60 cases were included in the research, aged 18-45 years were enrolled, and were split equally into two groups: Group A: obtained HFNC with FiO2 40% and flow 60L, Group B: obtained Nasal cannula 6L with 100% O Results: HFNC was effective in hindering hypoxia in obese cases experiencing upper GIE, unlike standard oxygenation. HFNC is also effective in ventilation and preventing the incidence of hypercapnia compared to standard oxygenation. Also, no intraoperative adverse events occurred in the high-flow group. Intubation and stopping the procedure did not occur in the study groups. Hypercapnia, modification of oxygen flow, and hypoxia (SPO2 < 90%) were significantly more frequent in the standard group. Conclusion: Obese patients who underwent an upper gastrointestinal endoscope procedure using HFNC with flow 60L and FIO2 40% reduced the occurrence of hypoxia that happened with sedation during the procedure in comparison to standard oxygenation.

Resumen

Antecedentes: Durante el procedimiento de endoscopía digestiva alta bajo sedación, pueden presentarse diversas complicaciones, siendo la hipoxia la más frecuente, lo que influye significativamente en la mortalidad y la morbilidad. Metodología: Se incluyeron 60 casos en la investigación, con edades comprendidas entre los 18 y los 45 años, divididos en dos grupos: Grupo A: se obtuvo CNAF con FiO2 del 40% y un flujo de 60 L; Grupo B: se obtuvo una cánula nasal de 6 L con 100% de O2. Resultados: La CNAF fue eficaz para prevenir la hipoxia en pacientes obesos con EGI superior, a diferencia de la oxigenación estándar. La CNAF también fue útil para la ventilación y la prevención de la hipercapnia en comparación con la oxigenación estándar. Además, no se produjeron eventos adversos intraoperatorios en el grupo de alto flujo. No se produjo intubación ni interrupción del procedimiento en los grupos de estudio. La hipercapnia, la modificación del flujo de oxígeno y la hipoxia (SPO < 90%) fueron significativamente más frecuentes en el grupo estándar. Conclusión: Los pacientes obesos sometidos a procedimiento de endoscopia gastrointestinal superior utilizando CNAF con flujo de 60L y FIO2 del 40% redujo la aparición de hipoxia que ocurrió con la sedación en comparación con la oxigenación estándar.

-

Introduction

The majority of gastrointestinal endoscopy (GIE) procedures are conducted in a profound sedation, supervised by an anesthesiology members in the operating theater. This sedation not only enhances the quality of the examination but also ensures optimal comfort of the patient and facilitates complex procedures[1].

Hypoxia is the major obstacle during GIE procedures executed under sedation[18], impacting 10%-30% of the cases. This issue arises primarily from pharyngeal blockage caused by introducing the endoscope in upper GIE and blowing, which directly compromises respiratory function by compressing the diaphragm. Furthermore, sedation leads to muscle relaxation and respiratory depression, heightening the risk of airway blockage and significantly reducing functional residual capacity[2].

To effectively prevent and treat hypoxia, the American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) and the American Society of Gastroenterology strongly endorse standard oxygenation therapy (SOT). Nevertheless, specific recommendations for the devices used in oxygenation remain absent. Various methods, like jet ventilation and innovative interfaces, have been explored but have not led to changes in clinical practice. High-flow nasal oxygenation (HFNO) is an intriguing option. Gases from HFNC are warmed, and moistened, enhancing patient acceptance and making the patient comfortable[17],[3].

High flow nasal Oxygenation (HFNO) is an invaluable tool that should be more widely embraced in the operating room, despite its frequent use in intensive care. The French Society of Anaesthesiology strongly advocates for using HFNO in patients susceptible to desaturation during the insertion of tracheal tube[4], highlighting its ability to significantly extend apnoea time and enhance patient safety. The benefits of HFNO in perioperative procedures are profound, particularly during awake fiberoptic intubation, where it consistently outperforms Standard Oxygen[3].

Obesity has become a global pandemic, with its rising prevalence leading to severe health consequences that are overwhelming healthcare systems around the world. defined by a Body Mass Index (BMI) over 30, obesity leads to numerous comorbidities, especially regarding respiratory health. It reduces lung volumes, causing restrictive patterns and lowering Functional Residual Capacity (FRC)[19], which can result in complications like atelectasis and hypoxemia. Additionally, obesity increases minute ventilation, making breathing more difficult while decreasing lung compliance and raising airway resistance. These changes heighten the risk of obstructive sleep apnea, underscoring the urgent need to address obesity[5].

-

Aim of the work

This study aims to compare the occurrence of moderate hypoxia during GIE, described as a SpO2 < 90% noticed between the induction of anesthesia and the finishing of the practice, in the HFNC group versus the SOT group.

-

Patients and Methods

This prospective, randomized, controlled, double-blinded clinical trial was performed after institutional ethical committee approval No. (FMASU MS 763/2023), clinical trial identifier: NCT06231836. This study was conducted in Ain Shams University hospitals from December 2023 to June 2024. It includes patients undergoing elective Upper GI endoscopes. A Written consent was acquired from every patient after explaining the procedure. Sealed envelope randomized technique.

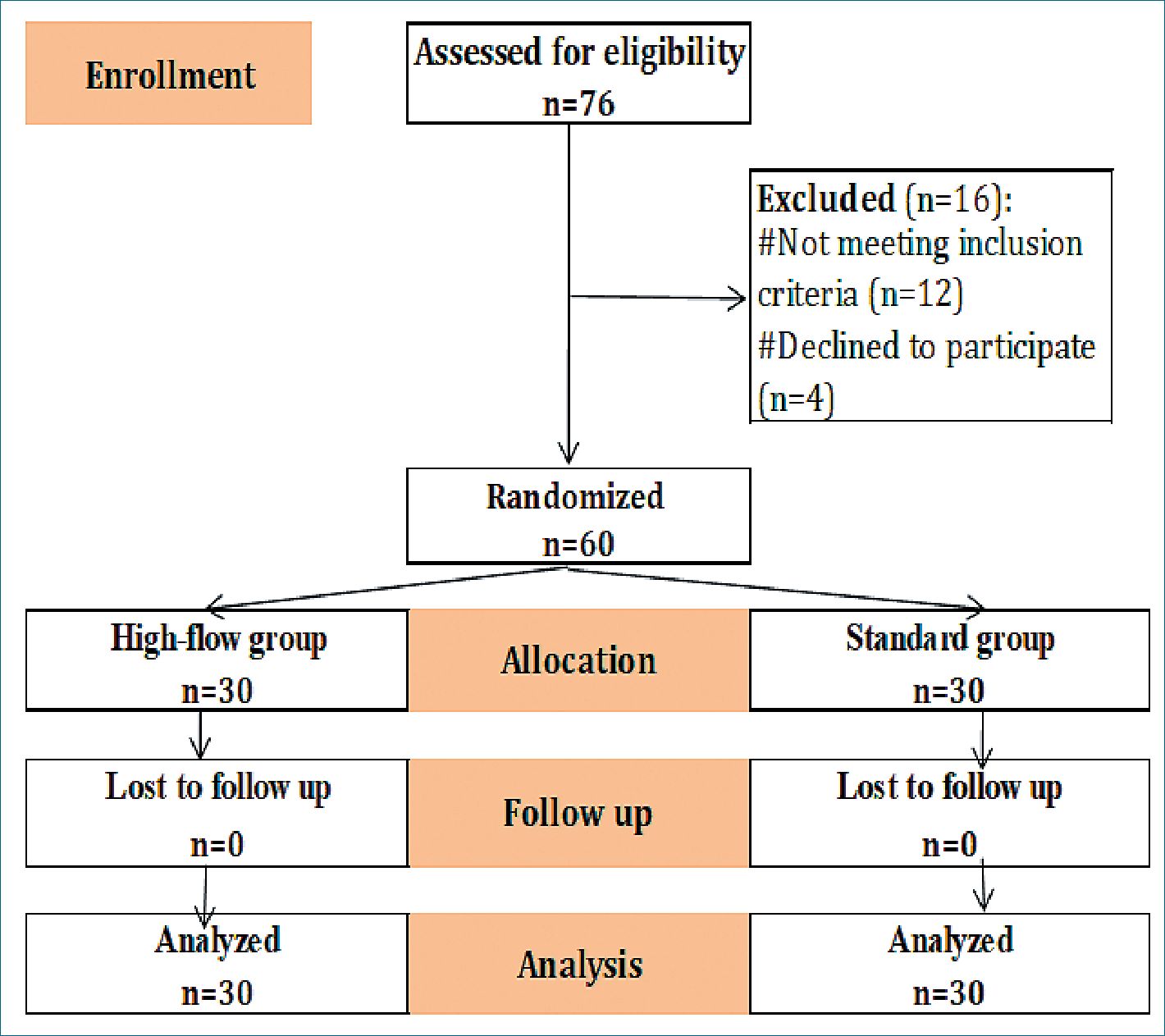

The study included patients aged from 18 to 45 of both sexes. ASA physical status II, Obese patient BMI > 35 to < 45. Patients were scheduled for upper GIE with planned sedation while maintaining spontaneous breathing. The duration of the procedure did not exceed 20 minutes. Patients who refused to participate in the study, urgent GIE, the need for patient intubation for the procedure, patients receiving home oxygen therapy, Tracheostomized patients, and Pregnant women were all excluded from the trial (Figure 1).

60 cases scheduled for elective gastrointestinal endoscopy (GIE) were randomly split into two equal groups using sealed opaque envelopes.

– **Group A:** Oxygen (O2) was administered via high-flow nasal cannula (HFNC).

– **Group B:** Oxygen (O2) was administered using standard oxygenation methods (nasal cannula).

All patients underwent preoperative assessments, which included taking their medical history, a physical examination, and laboratory evaluations. They were informed about the study design, objectives, tools, and techniques involved. Written consent was acquired from every patient immediately prior to the procedure. Upon arrival in the operating theater, baseline vital signs-including ECG, mean arterial blood pressure(MABP), heart rate(HR), and oxygen saturation-were recorded. Intravenous access was established, and SpO2 levels were measured in ambient air. A baseline arterial blood gas (ABG) sample was collected and documented to compare the partial pressure of carbon dioxide (PaCO2) before and after the procedure. Preoxygenation was performed using a simple face mask at a flow rate of 10 liters per minute with 100% oxygen for 3 minutes before induction. Induction involved administering an initial bolus of propofol at a dosage of 0.5-1 mg/kg IV, followed by additional boluses of 10-20 mg as needed based on the patient’s condition[6].

In Group A (the interventional group), patients underwent preoxygenation for 3 minutes, followed by induction. Oxygen was then administered via High-Flow Nasal Oxygen (HFNO) at a flow rate of 60 L/min, with the fraction of inspired oxygen (FiO2) set at 40%. This FiO2 setting was chosen to equate the oxygen levels in both groups and to minimize the hazard of hypoxia and hypercapnia.

In Group B (the control group), patients were also preoxygenated for 3 minutes. After induction, oxygen was administered via a nasal cannula at a flow rate of 6 L/min.

We maintained a consistent FiO2 in both groups during preoxygenation and throughout the practice to ensure that the SOT group was not disadvantaged. This comparable FiO2 allowed us to assess whether the benefits of HFNO-induced positive end-expiratory pressure (PEEP) and dead space washout could be demonstrated.

Throughout the process, the investigator had the discretion to increase the FiO2 or gas flow in response to any instances of desaturation or other needs:

– In Group A (the HFNO group), the FiO2 could be raised

from 40% to 100%, and the flow could be elevated from 60 L/min to 70 L/min.

– In Group B (the SOT group), the flow could be increased to 10 L/min.

If a patient’s oxygen saturation dropped to 85%, we implemented maneuvers to maintain upper airway patency, such as head tilt-chin lift and jaw thrust. Should desaturation persist despite these maneuvers, HFNO or SOT would be discontinued, and an alternative oxygen therapy method (such as a face mask or laryngeal mask) would be employed. If oxygenation could not be maintained through any method, we would halt the procedure and permit tracheal intubation to secure the airway and preserve oxygenation. Throughout all instances, investigators carefully documented every event in the case report form.

At the end of the gastrointestinal endoscopy (GIE), patients were moved to the post-anesthesia care unit, marking the conclusion of the interventional period. High-Flow Nasal Oxygen (HFNO) was not utilized in the recovery room. Instead, Standard Oxygen Therapy (SOT) was promptly implemented to all patients until it was not needed, by our recent practices. All patients were monitored for 30 minutes in the post-anesthesia care unit before being transferred to the ward, which served as the endpoint of the study. Arterial blood gases (ABGs) were collected in the post-anesthesia care unit to assess the hazard of hypercapnia among the patients in our study.

-

Sample size

Utilizing the PASS 15 software for calculating sample size, with a power set at 80% and an alpha error of 0.05, it is projected that 30 cases in each group will be required to identify the difference in moderate hypoxia rates (SpO2 < 90%) between the two groups, assuming the rate in the High-flow oxygenation group is 0% and in the standard oxygenation group is 20%. “Jonathan et al., 2023”[7].

-

Statistical methods

The gathered data were organized, and statistically evaluated using IBM SPSS Statistics (Statistical Package for Social Sciences) software, version 28.0, from IBM Corp., Chicago, USA, 2021. Quantitative data were assessed for normality through the Shapiro-Wilk Kolmogorov-Smirnov test; if they followed a normal distribution, they were presented as mean ± SD (standard deviation) along with the minimum and maximum values of the range and then analyzed using an independent t-test. Qualitative data were reported as frequencies and percentages and subsequently compared using the Chisquare test and Fisher’s Exact test. A p-value of < 0.050 was considered significant, while anything above that was deemed non-significant.

Figure 1. Flow chart of the study.

-

Results

Groups were comparable regarding Patient’s characteristics (in terms of age, ASA, height, and BMI) and operation duration (Table 1).

Minimum intraoperative oxygen saturation was significantly higher in high-flow group.

No intraoperative adverse events occurred in high flow group. Intubation and stopping the procedure did not occur in the study groups. Hypercapnia, modification of oxygen flow and hypoxia (SPO2 < 90%) were significantly more frequent in standard group (Table 2).

Minimum oxygen saturation in the recovery room was significantly higher in high-flow group. The incidence of hypoxia (SpO2 < 92%) was significantly less frequent in high-flow group (Table3).

Table 1. Demographic characteristics between the studied groups

| Variables | High-flow group (total = 30) | Stndard group (total = 30) | p-value | |

| Age (years) | 32.8 ± 5.8 | 34.4 ± 6.1 | ^0.286 | |

| Sex | Male | 16 (53.3%) | 18 (60.0%) | #0.602 |

| (n, %) | Female | 14 (46.7%) | 12 (40.0%) | |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 40.1 ± 2.0 | 39.7 ± 2.5 | ^0.447 | |

| ASA (n, %) | II | 30 (100.0%) | 30 (100.0%) | NA |

| Operation duration (minutes) | 14.9±2.4 | 15.5 ± 2.3 | ^0.331 | |

ASA: Amercan association of anaethiologistis; BMI: Body mass index; NA: Not applicable; independent t-test; #Chi square test.

Table 2. Intraoperative outcomes between the studied groups

| Outcomes | High-flow group (total = 30) | Stndard group (total = 30) | p-value | Relative effect Mean ± SE 95% CI |

| Minimum oxygen saturation (%) | 94.4 ± 2.7 | 90.3 ± 6.4 | 0.002* | 4.0 ± 1.3

1.5 – 6.6 |

| Hypercapnia | 0 (0.0%) | 11 (36.7%) | #< 0.001* | NA |

| Modification of oxygen flow | 0 (0.0%) | 7 (23.3%) | §0.011* | NA |

| Nasal mask | 0 (0.0%) | 4 (13.3%) | §0.112 | NA |

| Laryngeal masl | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (3.3%) | §0.999 | NA |

| Intubation | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | NA | NA |

| Hypoxia (SPO2 < 90%) | 0 (0.0%) | 9 (30.0%) | §0.002* | NA |

| Stop the procedure | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | NA | NA |

NA: Not applicable; ^indepednent t-test; #Chi square test; §Fisher’s Ecact test; Relative effect: Effect in high-flow group relative to that in standard group; CI: Confidence interval.

-

Discussion

Hypoxia poses a critical challenge for anesthesiologists during invasive procedures like gastrointestinal endoscopies (GIE), particularly in spontaneously breathing patients who are under deep sedation. As the complexity of diagnostic and therapeutic procedures increases and more patients with significant comorbidities seek care, the need for deep sedation is rising. Deep sedation and general anesthesia not only enhance patient comfort but can also significantly enhance the effectiveness and diagnostic yield. Therefore, it is imperative to prioritize the safety of these procedures to ensure positive outcomes for patients undergoing deep sedation[8].

HFNO (High-Flow Nasal Oxygen) has established itself as a vital tool in critical care units and is now making significant strides in operating rooms to optimize preoxygenation prior to anesthesia induction. However, there remains a notable gap in data regarding the application of HFNO during gastrointestinal endoscopies (GIE), especially for patients with comorbidities. Considering that hypoxemia is relatively rare in healthy individuals and recognizing that HFNO comes at a higher cost than standard oxygen therapy (SOT), we are committed to focusing our efforts solely on patients who are at the greatest risk of desaturation. This targeted approach ensures that we maximize patient safety and outcomes in this critical setting[8].

In our pursuit of practicality,we designed the study to promote changes in current practices. It was important to ensure that the initial FiO2 (fraction of inspired oxygen) was kept the same for both groups to avoid disadvantaging the control group. Most studies have compared high-flow nasal oxygen (HFNO) with 100% FiO2 to standard oxygen delivered at 2-5 liters per minute. This flow rate typically results in a FiO2 of approximately 28% to 45%[9].

In this study, both groups kept comparable levels of FiO2 to assess the advantages of High-Flow Nasal Oxygen (HFNO), concentrating on induced PEEP and the clearance of dead space. The HFNO group had a peak gas flow rate of 60 L/min, which varied from previous studies. Additionally, all patients underwent preoxygenation before the induction process.

This study showed a low incidence of hypoxia with using high flow nasal cannula unlike standard oxygenation and there was no need for maneuvers to maintain the airway or need for invasive ventilation with HFNC, unlike standard oxygenation.

In a multi-center randomized trial, HFNO (FiO2 100% and gas flow from 30 to 60 L/min) notably reduced the occurrence of hypoxia (from 8.4% to 0%) in comparison to SOT (2 L/min with nasal cannula in healthy cases during GIE[10].

Another trial found similar results, indicating that high- flow nasal oxygen (HFNO) reduced the hypoxic events when compared to standard oxygen therapy (SOT) during upper gastrointestinal endoscopy in healthy patients (ASA I and II) [11]. The study compared three groups: a control group using a standard oxygen cannula (5 L/min), a group with HFNO (30 L/min at 100% oxygen), and a group using a mandibular advancement bite block with a standard cannula. Both HFNO and mandibular advancement groups showed lower hypoxia rates than the control, although the HFNO group had a higher incidence of hypoxia than the MA group, possibly due to the lower flow rate used.

Kim et al.[12], demonstrated that the use of HFNC (FiO2 100% and 60 L) improved oxygenation during (ERCP) in prone position, in comparison to conventional treatment with a nasal cannula at 6 L/min. But showed some limitations, including unblinded grouping arrangement, the absence of arterial blood gases analysis, and not utilizing other markers for assessing ventilation.

Table 3. Recovery room outcomes between the studied groups

| Outcomes | High-flow group (total = 30) | Stndard group (total = 30) | p-value | Relative effect Mean ± SE/RR 95% CI |

| Minimum oxygen saturation (%) | 96.3 ± 3.4 | 92.1 ± 4.5 | < 0.001* | 4.2 ± 1.0

2.2 – 6.3 |

| Hypoxaemia (SpO₂ ≥92%) | 2 (6.7%) | 16 (53.3%) | #< 0.001* | 0.13

0.03 – 0.50 |

NA: Not applicable; ̂ Indepednent t-test; #Chi square test; §Fisher’s Ecact test; Relative effect: Effect in high-flow group relative to that in standard group; RR: Relative risk; CI: Confidence interval.

Jonathan et al.[7], observed a significant difference between the two groups HFNC (FiO2 100% and flow 60 L) and Nasal (2 L). The HFNC group had markedly fewer instances of mild and moderate hypoxia compared to the SOT group (5% vs 31% and 0% vs 16%, respectively). However, since the groups used different FiO2 levels and varied definitions of hypoxia, it remains indistinct what duration and severity of hypoxia may lead to a clinical impact.

Ee et al.[13], compared HFNC(FiO2 100%and flow 30 L) and nasal cannula (6 L) and found that There were notable changes between both groups in minimum SpO2 and occurrence of hypoxia group Nasal versus group HF; 90.3 ± 9.7% versus 95.7 ± 9.0%, 25 (35.2%) versus 10 (11.4%)) but not relevant, the occurrence of hypercapnia (PtCO2 > 60 mmHg) was elevated in the HFNC group than in the SOT group [32 (52.5%) versus 21 (38.9%)]. This study used different parameters of HFNC and this may be the cause of no significant difference in hypercapnia in both groups.

Nay et al.[14], comparing HFNC (gas flow 70 L, FiO2 50%) to SOT via nasal cannula (6 L) show that a diminish in SpO2 92% occurred in 9.4% for HFNC and 33.5% for the standard oxygenation groups. This study has several limitations as not being blinded, the anesthesia regimen was not standardized, differences in preoxygenation FiO2 levels between the groups, and the adequacy of ventilation can not be assessed.

The only study, Riccio et al.[15], reported varied outcomes during colonoscopy. This trial conducted at a single center involving morbidly obese patients was discontinued due to a lack of efficacy. At comparable FiO2 levels (36%-40% at 60 L/ min in the HFNO group versus Oxygen flow of 4 L/min in the SOT group), the use of HFNO did not decrease the incidence of hypoxia (39.3% vs 45.2%, respectively, p = 0.79). Nevertheless, there are indications that HFNO may be advantageous for patients predisposed to sleep apnea syndrome.

Mohamed et al.[18], The findings indicated that high- flow nasal cannula (HFNC) is generally well-accepted, safe, and effectively reduces the occurrence of hypoxia. The study varies because it took place in the ICU with a diverse range of age groups and ASA classifications; however, it has certain limitations since it was not conducted in a blinded manner, which could introduce bias.

Yin X et al.[20], The study found that high-flow nasal cannula (HFNC) is superior to standard nasal cannula in reducing hypoxia. Nevertheless, it’s crucial to emphasize that this research concentrated on a particular age group, specifically those aged 60 and above.

Eugene et al.[16], the prospective multi-center randomized controlled ODEPHI study showed that HFNO (FiO2 100% and flow 70 L) may diminish the occurrence of hypoxia during GIE under deep sedation in comparison to SOT (6 L) but there were limitations of different FiO2 despite using the initial same FiO2 during preoxygenation.

This study rigorously investigates the hypothesis that High-Flow Nasal Oxygen (HFNO) can significantly decrease the occurrence of hypoxia during gastrointestinal endoscopy (GIE) conducted under deep sedation, in comparison to Standard Oxygen Therapy (SOT), while ensuring a similar fraction of inspired oxygen (FiO2). By addressing the shortcomings of previous research that utilized varying FiO2 levels-resulting in inadequate oxygen flow and lower effective FiO2-this study meticulously calibrates gas delivery in both groups to achieve comparability in oxygen levels. Our goal is to demonstrate that HFNO not only enhances oxygenation but also leverages the benefits of positive end-expiratory pressure (PEEP) and efficient dead space clearance, thereby offering a superior alternative for patients undergoing GIE.

In this study, we’re focusing on whether a high-flow nasal cannula (HFNC) provides advantages over standard oxygen therapy, despite its higher cost. We had done a 3-minute pre-oxygenation for both groups using the same face mask, FiO2, and flow rates. Both would receive the same medication (propofol) while avoiding opioids to prevent breathing issues. We maintained the same FiO2 throughout the procedure and compared PaCO2 levels before and after in both groups to assess ventilation.

-

Limitations of study

This research has multiple limitations. We switched the preoxygenation device from a face mask to either HFNC or nasal, which exposed patients to ambient air during the transition and reduced preoxygenation efficacy. The study involved a small group of obese individuals aged 18 to 45 with an ASA classification of II and a BMI between 35 and 45, excluding those over 45, with a BMI over 45, or other co-morbidities. While these patients often have poorer health, they still need sedation for gastrointestinal endoscopy. Further studies are needed to determine the benefits of HFNC oxygenation in this demographic, as results are based on single-center trials.

-

Conclusion

This comparative study demonstrated that obese patients who underwent an upper gastrointestinal endoscope procedure by HFNC with flow 60 L and FIO2 40% reduced the occurrence of hypoxia that happened with sedation during the procedure in comparison to the usage of standard oxygenation.

HFNC was found to be significantly more effective than standard oxygenation regarding ventilation, intraoperative adverse events, hypercapnia, modification of oxygen flow, and desaturation in the postoperative period.

-

References

1. Jeurnink SM, Steyerberg E, Kuipers E, Siersema P. The burden of endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) performed with the patient under conscious sedation. Surg Endosc. 2012 Aug;26(8):2213–9. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-012-2162-2 PMID:22302536

2. Mador MJ, Nadler J, Mreyoud A, Khadka G, Gottumukkala VA, Abo-Khamis M, et al. Do patients at risk of sleep apnea have an increased risk of cardio-respiratory complications during endoscopy procedures? Sleep Breath. 2012 Sep;16(3):609–15. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11325-011-0546-5 PMID:21706289

3. Zhang YX, He XX, Chen YP, Yang S. The effectiveness of high-flow nasal cannula during sedated digestive endoscopy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Med Res. 2022 Feb;27(1):30. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40001-022-00661-8 PMID:35209948

4. Langeron O, Bourgain JL, Francon D, Amour J, Baillard C, Bouroche G, et al. Intubation difficile et extubation en anesthésie chez l’adulte. Anesthésie & Réanimation. 2017;3(6):552–71. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anrea.2017.09.003.

5. Kaye AD, Lingle BD, Brothers JC, Rodriguez JR, Morris AG, Greeson EM, et al. The patient with obesity and super-super obesity: perioperative anesthetic considerations. Saudi J Anaesth. 2022;16(3):332–8. https://doi.org/10.4103/sja.sja_235_22 PMID:35898529

6. Nishizawa T, Suzuki H. Propofol for gastrointestinal endoscopy. United European Gastroenterol J. 2018 Jul;6(6):801–5. https://doi.org/10.1177/2050640618767594 PMID:30023057

7. Jonathan N, Leonardo Z, Cheng TP, et al. High-flow nasal cannula oxygen therapy versus conventional oxygen therapy in prolonged upper GI endoscopy: a randomized controlled trial. iGIE. 2023;2(2):131–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.igie.2023.02.002.

8. Thiruvenkatarajan V, Dharmalingam A, Arenas G, Wahba M, Steiner R, Kadam VR, et al. High-flow nasal cannula versus standard oxygen therapy assisting sedation during endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography in high risk cases (OTHER): study protocol of a randomised multicentric trial. Trials. 2020 May;21(1):444. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13063-020-04378-z PMID:32471494

9. Hardavella G, Karampinis I, Frille A, Sreter K, Rousalova I. Oxygen devices and delivery systems. Breathe (Sheff). 2019 Sep;15(3):e108–16. https://doi.org/10.1183/20734735.0204-2019 PMID:31777573

10. Lin Y, Zhang X, Li L, Wei M, Zhao B, Wang X, et al. High-flow nasal cannula oxygen therapy and hypoxia during gastroscopy with propofol sedation: a randomized multicenter clinical trial. Gastrointest Endosc. 2019 Oct;90(4):591–601. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gie.2019.06.033 PMID:31278907

11. Teng WN, Ting CK, Wang YT, Hou MC, Chang WK, Tsou MY, et al. High-Flow Nasal Cannula and Mandibular Advancement Bite Block Decrease Hypoxic Events during Sedative Esophagogastroduodenoscopy: A Randomized Clinical Trial. BioMed Res Int. 2019 Jul;2019:4206795. https://doi.org/10.1155/2019/4206795 PMID:31380421

12. Kim SH, Bang S, Lee KY, Park SW, Park JY, Lee HS, et al. Comparison of high flow nasal oxygen and conventional nasal cannula during gastrointestinal endoscopic sedation in the prone position: a randomized trial. Can J Anaesth. 2021 Apr;68(4):460–6. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12630-020-01883-2 PMID:33403549

13. Lee S, Choi JW, Chung IS, Kim DK, Sim WS, Kim TJ. Comparison of high-flow nasal cannula and conventional nasal cannula during sedation for endoscopic submucosal dissection: a retrospective study. Therap Adv Gastroenterol. 2023 Aug;16:17562848231189957. https://doi.org/10.1177/17562848231189957 PMID:37655054

14. Nay MA, Fromont L, Eugene A, Marcueyz JL, Mfam WS, Baert O, et al. High-flow nasal oxygenation or standard oxygenation for gastrointestinal endoscopy with sedation in patients at risk of hypoxaemia: a multicentre randomised controlled trial (ODEPHI trial). Br J Anaesth. 2021 Jul;127(1):133–42. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bja.2021.03.020 PMID:33933271

15. Riccio CA, Sarmiento S, Minhajuddin A, Nasir D, Fox AA. High-flow versus standard nasal cannula in morbidly obese patients during colonoscopy: A prospective, randomized clinical trial. J Clin Anesth. 2019 May;54:19–24. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinane.2018.10.026 PMID:30391445

16. Eugene A, Fromont L, Auvet A, Baert O, Mfam WS, Remerand F, et al. High-flow nasal oxygenation versus standard oxygenation for gastrointestinal endoscopy with sedation. The prospective multicentre randomised controlled ODEPHI study protocol. BMJ Open. 2020 Feb;10(2):e034701. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2019-034701 PMID:32075842

17. Wang L, Zhang Y, Han D, Wei M, Zhang J, Cheng X, et al. Effect of high flow nasal cannula oxygenation on incidence of hypoxia during sedated gastrointestinal endoscopy in patients with obesity: multicentre randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2025 Feb;388:e080795. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj-2024-080795 PMID:39933757

18. Mohamed AM, Selima WZ. HFNC Oxygen Therapy vs COT in Prolonged Upper Gastrointestinal Endoscopy Inside the ICU: A Prospective, Randomized, Controlled Clinical Study. Indian J Crit Care Med. 2025 Mar;29(3):223–9. https://doi.org/10.5005/jp-journals-10071-24919 PMID:40110237

19. Carron M, Tamburini E. High flow nasal oxygenation in sedated gastrointestinal endoscopy for patients with obesity. BMJ. 2025 Feb;388:r184. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.r184 PMID:39933789

20. Yin X, Xu W, Zhang J, Wang M, Chen Z, Liu S, et al. High-Flow Nasal Oxygen versus Conventional Nasal Cannula in Preventing Hypoxemia in Elderly Patients Undergoing Gastroscopy with Sedation: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Int J Med Sci. 2024 Mar;21(5):914–20. https://doi.org/10.7150/ijms.91607 PMID:38617012

ORCID

ORCID